Thanksgiving, a Celebration of Inequality

For decades, Gilded Age populists and secularist crusaders criticized the holiday’s gospel of abundance.

For over a decade, Fox News has made it a talking point that Christmas is under siege from liberals. Bill O’Reilly has promoted the meme with almost singular relish, but the notion that secularists are conspiring to suppress Christmas has become a recurrent battle cry on the right. A wan expression of seasonal greetings—say, a tossed-off “Happy holidays” in place of “Merry Christmas”—has become an apocalyptic sign of the end of Christian America. Indeed, the war on Christmas is among the liberal plots that President-elect Donald Trump has explicitly pledged to foil.

Christmas, though, has long been beleaguered as a religious holiday. The Puritans found it such a mix of bacchanalian paganism and Catholic ritualism that they tried to erase it entirely from the Protestant calendar. One of the most effective evangelists of the early republic, the Methodist Francis Asbury, simply despaired of redeeming the holiday’s drunken excess: “Christmas day,” he lamented in 1805, “is the worst in the whole year on which to preach Christ.” No wonder that most 19th-century liberals and freethinkers did not worry very much about the need to secularize Christmas: The holiday season belonged to them at least as much as to churchgoers, what with the street revelry, the store-window Santas, the mistletoe, the feasting, the shopping and gift-giving.

Thanksgiving, however, was another matter. To secularists, that holiday, sanctified by the story of the Pilgrims and by solemn invocations of divine blessing, was definitely worth fighting over. As one free-thought editorial proclaimed in 1889, “we hope to live long enough to see a purely human thanksgiving day, with no hint of God in it, with no religious meaning ascribed to it.”

The debate over what tone presidents should set with their Thanksgiving proclamations was as old as the nation itself. John Adams and Thomas Jefferson had famously split over the issuing of such civic religious pronouncements during their presidencies (Adams assented; Jefferson refused). But the conflict escalated during and after the Civil War, as the holiday was promoted as a national rite of reconciliation and patriotic concord. In 1863, Abraham Lincoln had proclaimed the first national Thanksgiving in language replete with religious allusion, imagining the Union under the “the ever-watchful providence of Almighty God” and imploring “the interposition of the Almighty hand to heal the wounds of the nation.”

Freethinkers and secularists—a small but vocal and vigilant minority—watched with disappointment as American presidents thereafter made an annual routine of such exhortations, effectively fusing Thanksgiving with the politics of religious nationalism. “The American people,” President Grover Cleveland typically intoned in 1885, “have always abundant cause to be thankful to Almighty God, whose watchful care and guiding hand have been manifested in every stage of their national life.” He encouraged all citizens to assemble in their respective houses of worship for prayers and hymns in order to give thanks to the Lord for the nation’s innumerable bounties.

Liberal secularists could not stand to let this recurring presidential call for devotion go unchallenged. It fundamentally violated their sense of strict Church-state separation—they believed that elected representatives, from presidents to governors to mayors, should not be in the business of enjoining religious observance upon Americans. They maintained that the government should not elevate believers over nonbelievers, whether by employing state-funded chaplains, granting tax exemptions to churches, inscribing In God We Trust on coinage, instating bans on buying liquor on Sundays, establishing religious tests for public office-holding, or by sanctifying fast and thanksgiving days. To these secularists, all the ways, big and small, in which the government signaled preference for a Protestant Christian nation over a secular republic had to be combatted.

Freethinkers, as the irreligious editors of the Boston Investigator explained, wanted instead “eternal separation” between Church and state, a breaking of all the “politico-theological combinations” that they saw sullying American public life. They wanted, in short, the full secularization of the state. Hence Thanksgiving was, to them, nonnegotiable: “If ministers desire a religious festival, let them appoint it in their churches,” the Investigator further editorialized. The president had “no constitutional right” to set apart a sacred celebration and entwine good citizenship with ecclesial supplication.

The critique of Thanksgiving for entangling Church and state was predictable secularist fare, the same turkey freethinkers carved up every year. “We [have] no objection to pumpkin pie,” the convicted blasphemer C. B. Reynolds insisted in 1891, “but protest against its being seasoned with theology.”

The censure got more tantalizing, though, as freethinking liberals increasingly leavened their attack in the 1880s and 1890s with populist indignation over Gilded Age inequality, greed, and exploitation. Not all secularists, of course, were economic populists, ready to express a fierce solidarity with labor and the dispossessed, but across the country, in one village after another, a freethinker or two or three often stood up to the complacent gospel of wealth and abundance given routine expression at Thanksgiving. Seeing the holiday as best suited to the day’s most prominent capitalists—Cornelius Vanderbilt, John D. Rockefeller, and company—these irreligious populists ripped into the celebration as a mockery of mortgaged farmers and starved wage laborers.

Nettie Olds of McMinnville, Oregon, was one of those local remonstrants. Active in free-thought circles from a young age, she took a leading role in organizing the First Secular Church of Portland in the early 1890s and promoted secular Sunday Schools as alternatives to the usual Protestant institutions. Taking to the lecture circuit, she encouraged superstition-free versions of the holidays, particularly Thanksgiving. At one “Secular Thanksgiving” she staged in Silverton, Oregon, in 1896, she first criticized the state’s governor for endorsing a religious observance that necessarily excluded “hundreds of honest Secularists.” But she quickly pivoted from there to a scathing indictment of the joyful prosperity the governor had invoked:

Moaning by the wayside are the wretched and dying, and along the pathways are strewn the victims of starvation and crime. Within the very shadow of the temple of Plenty, Poverty sits and weeps; within the sound of the jingle of millions, helpless beings toil and slave for the bare necessaries of existence.

To Olds, a holiday that overlooked such distress—the “barbarism” of the industrial economy—and simply dwelled instead on the nation’s teeming abundance was an abomination.

Another sturdy village secularist who made the same plea was G. H. Walser. Dreaming of a freethinking utopia, Walser had promoted his hometown of Liberal, Missouri, in the 1880s as a secularist refuge where residents could congregate in a building called Universal Mental Liberty Hall and where churches and clergy would be kept out.

Such notions obviously did not sit well with neighboring communities, and soon Liberal became the target of wayfaring evangelists who demonized it as a hotbed of atheism, materialism, and immorality. Those attacks only heightened secularist hopes for Liberal. “All eyes are on Missouri,” the great agnostic orator Robert Ingersoll remarked of Walser’s experiment, eagerly waiting to see if secularist liberalism could be made the basis of a flourishing community.

For this communal venture to work—and it did okay for a decade or so, amid much controversy—alternative secular rituals were required. That included the invention of a “Rational Thanksgiving,” about which Walser, who doubled as the town’s poet, dutifully versified:

If God gave us peace and plenty of mammon,

And gladdened our hearts with provisions in store:

Who should the thousands thank dying from famine? …

If the rich should thank God because they’re not poor,

For their gold in the bank and government bonds:

For ships on the sea and railroads on shore,

For great lowing herds and rich fertile lands,

With a life of pleasure and ease;

Who should the poor thank for poverty’s wage;

For hollow-eyed Want, that stands at the door;

For hunger and rags and homeless old age;

For the kicks and the cuffs that fall to the poor,

And other sweet morsels like these?

For Walser, a Rational Thanksgiving upended the nation’s god of mammon, and stressed equalizing the economy—or, in his plain phrase, “putting business affairs into more even channels.”

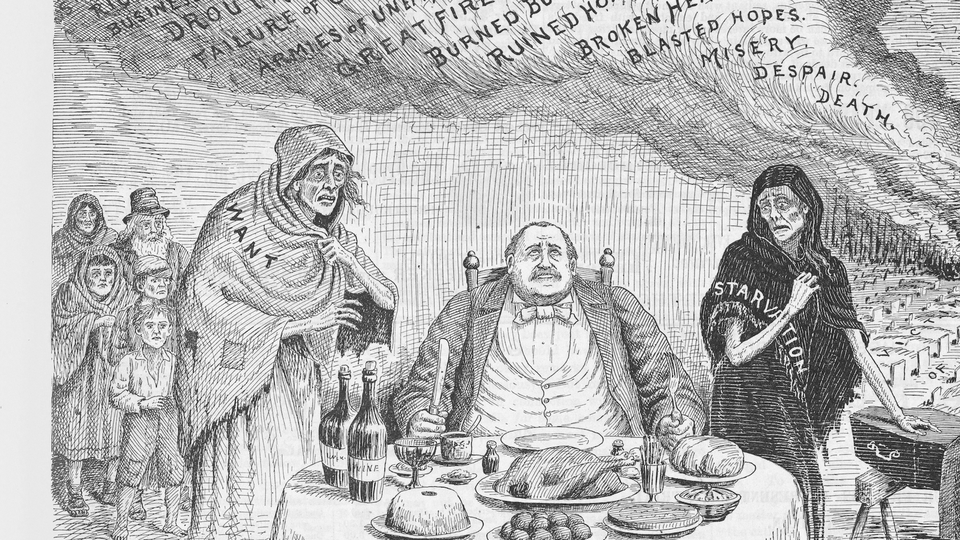

Perhaps the sharpest attack on Thanksgiving came from Watson Heston, an atheist cartoonist and hardscrabble populist. Holed up in Carthage, Missouri, about 40 miles from Walser’s experiment, Heston created more than 1,200 cartoons from 1885 to 1900 satirizing Christianity and promoting secularism, most of which appeared in the Truth Seeker, the banner free-thought journal of the era. The beloved artist of the country’s unbelievers, Heston warred against Thanksgiving from one year to the next. Despite the notoriety of his images, he never made a comfortable wage as a portrait painter or cartoonist. Penurious and often in failing health, he was utterly disdainful of Thanksgiving’s aura of divine blessing and pious gratitude. “I have no turkey—no, not even so much as poor frozen-toed rooster—to offer up as a burnt offering,” he observed as the holiday approached in 1884. “Really I am sorely puzzled what to return thanks for.”

O LORD, Let the millions of hungry beggars and tramps in this bountiful land be thankful that the dogs have not eaten all the crumbs that fall from the rich man’s table. … Let the starving miners in Illinois and elsewhere be thankful that they have not yet been compelled to eat each other. Let the wretched sewing women in our large cities be thankful for the CHRISTIAN CHARITY that gives them 37 1/2cts per dozen for making shirts.

The same populist ire flared in Heston’s Thanksgiving cartoon of 1896, which depicted President Grover Cleveland preaching to a crowd and demanding fealty to a mannequin made of sacks of cash. Heston derided the money-bag idol as cold comfort for “THE DISINHERITED,” who stood forlornly in the background. “We thank thee,” Heston wrote in mock supplication to the “God of Holy Grover,” that “perhaps one percent of the rich may dole out a small portion to the poor in charity, of what they have stolen from them legally”—a populist point that Heston repeated with ritualized familiarity.

To him, Thanksgiving, with its officially sanctioned theology of divine abundance, disdained those who did not share in that prosperity. The celebration, he thought, legitimated a gospel of wealth in which poverty signaled moral failing and affluence righteous living.

Secularists never let go of their campaign against Thanksgiving. Disentangling Church and state always remained front and center, but sometimes the old populist fire still burned. The American Association for the Advancement of Atheism, organized in 1925 in the wake of the Scopes trial to combat Fundamentalist anti-evolutionism, was nothing if not pugnacious. As the nation sank into the Great Depression, the group broadened its platform and urged President Herbert Hoover to desist from the “irrational act” of “a public Thanksgiving to God.” When the president predictably failed to take heed, the association lobbied instead for equal time for its sardonic vision, suggesting a new national holiday called “Blamegiving Day.” As the association argued in support of its mordant celebration, “cropless farmers” and “jobless workers”—all “the victims of Divine Negligence”—deserved better than civic religious platitudes about the nation’s spiritual and temporal blessings.

Today’s nonbelievers often see the quandaries of Thanksgiving observance as more familial than socioeconomic. Can an atheist say a humanist grace, they wonder? Or, how can an irreligious Millennial get through the holiday meal without offending older religious relatives? But the impulse to turn Thanksgiving to secular-populist ends abides alongside those household dilemmas. In another Gilded Age of massive income inequality, Thanksgiving has emerged anew as a time to amplify core progressive themes—to focus on the 99 percent over the 1 percent, to make the case for a living wage from employers such as Walmart, to critique the extra shifts demanded by retailers for Black Friday or even Thanksgiving Day itself, or to underline the importance of keeping immigrant families together. “Communist Candidate Bernie Sanders Calls for a Ban on Thanksgiving,” a headline to one satirical news story announced during last year’s primary season. It was all tongue-in-cheek, of course, but the long-standing secular-populist critique of the holiday gives that flippant humor some bite.

The secularist war on Thanksgiving was always tenuous. It was never going to carry the holiday into public oblivion any more than the supposed war on Christmas is going to usher Baby Jesus into cultural obscurity. Presidential proclamations blessing the holiday remain de rigueur; Lincoln’s approach endures. No matter how quixotic, the freethinking populist complaint is a heaping reminder that a lot more is potentially at stake in the holiday’s economy (and its theology) than the inauguration of the most important shopping season of the year.