Blair Jones and Deborah Beckmann are Managing Directors at Semler Brossy Consulting Group LLC. This post is based on their Semler Brossy memorandum, originally published in Directorship magazine.

Related research from the Program on Corporate Governance includes The Perils and Questionable Promise of ESG-Based Compensation (discussed on the Forum here) by Lucian A. Bebchuk and Roberto Tallarita.

One of a board’s most important responsibilities is selecting the CEO. Most boards have annual succession planning discussions and robust procedures to prepare for a transition. But, recognizing both the shrinking of leaders’ tenures and the shifting skill sets needed for future success, many boards are now making succession planning a continual process. Centered on an ongoing conversation with the CEO, the process might start with one or two candidates and then expand, internally or externally, as needed. Even under ideal conditions, however, succession is a sensitive process.

One way that boards can smooth the process is to prepare for a variety of compensation decisions. Compensation sends important signals, both intended and unintended. Choices about pay should support the motivation and retention of leading candidates as well as individuals in key supporting roles.

For example, the pay of internal candidates will likely need to change as their roles and mandates expand and as the board evaluates their capabilities. With the actual transition, the board may need to adjust compensation for the new CEO, the former CEO, and other executives remaining with the organization, along with any new senior leaders. One-time actions may be required to maintain stability throughout the leadership change.

A change in leadership may also present a transition to a new business strategy and management style, which should be reflected in the compensation design, including the choice of incentive measures, the types of long-term incentive vehicles granted, and how goals are set. These decisions communicate to stakeholders the company’s priorities going forward as well as the balance between individual accountability and team orientation.

THE IMPORTANCE OF DYNAMIC SUCCESSION CONVERSATIONS

The number of CEO transitions has been rising. Among S&P 500 companies, it went from 40-plus transitions per year in the early 2010s to the high 50s by the end of 2020. Transitions fell a bit during the pandemic, as usually happens in a crisis, but are expected to pick up again this year.

The executive search and consulting firm Spencer Stuart found that ongoing disruption slowed CEO transitions in 2021 to 49 S&P 500 companies. However, the firm’s research on CEO successions during periods of crisis shows that while boards tend to deprioritize transitions during turbulent times, transitions rebound as uncertainty wanes, often spiking to record levels two years after the depth of a crisis.

Succession plans must be dynamic because potential internal candidates may move to other companies, their performance in an expanded role may call their candidacy into question, or the company’s strategy, external operating environment, and related skill requirements may change. Boards cannot assume that succession plans from previous years are still valid. They need to plan for transitions on an ongoing basis, with ongoing conversations with the current CEO.

Since boards have the final decision even when a well-regarded CEO retires, directors must stay apprised of the company’s bench and monitor recruiting, promotion, and retention across the company. Succession is a primary board responsibility, and boards need to ensure that they have a well-thought-out process that considers the ramifications for compensation.

Below we’ve grouped board efforts according to the four phases of succession: no imminent change, change within a few years, change now, and post-succession. In every phase, directors have substantial decisions to make.

PHASE ONE: NO IMMINENT CHANGE

The board is checking regularly with the CEO, and the expectation is that there will be no change for at least two years. Assuming the directors are satisfied with the leader’s performance, that’s good news. Still, the board should have a regular process in place for succession planning.

That process involves three main efforts. First, the board needs to be aware of the company’s overall pipeline for future leaders, from mid-level managers on up. Who is available to step up and eventually take over? Most of these individuals could be candidates for other C-suite positions, as well.

Second, what can the board do to better identify and support the development of those potential internal successors? Directors might work with the CEO or other executives to make sure those candidates widen their experience. Compensation can help support the process. If you have identified rising stars and potential successors, does their pay reflect the high value the company places on them? Does their long-term incentive mix encourage them to stay? If their responsibilities are expanded, will their compensation be adjusted appropriately? Do their incentives need to change to capture the priorities of their new roles?

Third, what skills are they missing that might matter for strategic success? A company’s evolving business strategy influences the talent strategy, and an annually adjusted skills-gap assessment is essential. Boards should likewise consider the diversity of the pipeline and assess the risk of key people leaving the company.

Companies usually prefer to hire from the inside, given the advantage of knowledge of the company, its culture, and its people. An outside CEO must work to get to know the organization and develop relationships, particularly if they plan an overhaul. That said, it has become a best practice for boards to look at external candidates, as well. Even if a board has no intention to hire from the outside, this exercise can help the board gain perspective on its internal candidates’ merits and development opportunities.

Despite the historical preference for internal candidates and more mixed transition success, external hires are increasing. In the same study mentioned above, Spencer Stuart found that 29 percent of new CEOs at large-cap companies came from outside the organization in 2020, up from 21 percent the year before. External hires typically come with higher pay requirements. A recent study by the Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania found that outside management hires at all levels typically receive 18 to 20 percent higher compensation despite lower performance ratings and higher exit rates than long-tenured internal managers.

Here as well, after viewing candidates through the eyes of the company’s future needs, boards might value them differently. Even if they decide to seek external candidates, they might want to adjust the compensation of internal picks accordingly.

Finally, this phase is a good time to identify an individual—usually a C-suite executive or a board director—who could serve on an interim basis in an emergency situation. Most boards conduct this conversation annually. It’s helpful to settle this question during a quiet period.

PHASE TWO: SUCCESSION IN THE NEXT TWO YEARS

Those ongoing discussions have led the CEO, the board alone, or both to decide that the company will need a new leader in the near future. The immediate question is whether a prime internal candidate already exists, the board needs to pick from a few potentials, or the board must conduct an external search. If the board has gone through phase one, it is already familiar with the company’s executive bench and can just update the profile of skills needed in the next CEO. Boards often work with an outside advisor such as a search firm to validate the CEO skills profile and assess internal and external candidates against that profile.

Even if the board has a satisfactory heir apparent, it still has much to decide. Should the board immediately signal the choice to the rest of the organization, which may help end the jockeying but might lead other candidates to bolt or lose motivation? Should the prime candidate take on new responsibilities, perhaps becoming president or chief operating officer, to broaden their preparation? Should the board adjust the lead candidate’s pay package accordingly?

Also, who is the backup candidate if the chosen successor does not work out? Is it someone who might also benefit from new responsibilities and adjusted compensation arrangements? Most boards find it helpful to have multiple backups in case the lead candidate is lured away or not up to the job, or, alternatively, if the transition is delayed.

The board also needs to consider timing. Investors as well as managers on the inside will pay close attention and could draw the wrong conclusions from signals that coincide with major company developments. Legal counsel should be involved throughout the process to help advise on any legal requirements for disclosures and appropriate timing.

If no clear successor exists, then the board has to step up and manage a full selection process. The CEO can certainly offer advice and guidance—after all, the CEO knows the company and its people better than the board. But directors must still do the work to make a knowledgeable decision on their own, building on their efforts in phase one.

Will the board manage the process as a horse race of potential successors? This approach has the benefit of enabling close comparison, but it often alienates candidates and distorts operations as colleagues take sides on who will “win.” Boards are looking not just at individual capabilities but also at how well a future C-suite would collaborate. Most companies do quietly signal to certain people that they are under consideration, with feedback about their strengths and development needs. Some or all of the candidates may need coaching and other support to fill perceived gaps.

As in phase one, boards might consider it a best practice to look at external candidates to compare against internal choices, however satisfactory those might already be. The assessment process, run in conjunction with an outside advisor, can be instrumental at this juncture, clarifying all candidates’ strengths and weaknesses, and confirming whether internal candidates have the preferred skill sets.

The board should consider new roles for potential internal candidates, possibly moving them to new areas to broaden their perspectives. Higher pay might be justified, but we caution against adding retention grants separate from position or performance. The possibility of becoming the CEO should be enough of a carrot. If a candidate is at risk of looking elsewhere, it may be a sign of low commitment that by itself might signal that the candidate is not right for the job.

Eventually the board must decide on a candidate, usually in partnership with the sitting CEO. But before any announcement, the board needs a plan for candidates not picked.

Horse races often lead to talented losing candidates going elsewhere. They’ve been recognized as CEO material, and their disappointment makes them open to appeals from recruiters. Their departure could be for the best, as losing candidates can prove disruptive to the new leader. Even without an explicit horse race, talented executives may see less opportunity with a new CEO, whether internal or external. Retention grants can make sense in this situation, but should be used sparingly and with a short duration. The goal is to show the executives that the company values their talents and to ensure a smooth transition—while still enabling the new CEO to pick his or her team.

A 2021 study by FW Cook looked at 65 large-cap companies with CEO transitions between 2010 and 2016. A full 40 percent of those firms issued retention grants related to a CEO transition to some or all of the named executive officers. But the grants helped keep losing candidates for only one year; after that, their effectiveness fell off dramatically compared to executives that did not receive such grants.

In some cases, a board has to deal with an unplanned transition. That usually happens because the CEO is demonstrably failing in the job and needs to move on, the CEO suddenly becomes incapacitated, or a scandal erupts. Rather than rush toward a new candidate, we recommend naming an interim CEO—preferably a person that the board already discussed and decided on in phase one. This is not a decision you want to be forced into on short notice, and the chosen individual may not be a long-term succession candidate. The board could also decide on a higher salary and target bonus, with some of the bonus tied to specific contributions expected of the interim leader. Some companies make special or increased equity grants depending on the expected timing of the interim assignment, especially if the temporary CEO must work to restore internal and external credibility.

WHEN COMPENSATION DECISIONS SUPPORT CEO SUCCESSION

PHASE THREE: JUST BEFORE THE SUCCESSION EVENT

Assuming a normal rather than forced transition, boards should also think ahead about the departing CEO. Will the outgoing leader become chair of the board in a clearly defined role? For how long? Often companies that opt for this transition plan it for six months to a year. Alternatively, the role of board chair might go to the new CEO or to an independent board member. If not the board chair, will the departing CEO be available for guidance after the transition in a consulting arrangement? Beyond that, will the departing CEO have any formal involvement with the company?

Each of these roles poses different compensation questions. For a CEO who is simply retiring, their remaining incentives and outstanding equity are typically predetermined by grant agreements and company policies. Most companies no longer offer perquisites to retiring CEOs. We studied disclosures from S&P 500 companies on post-retirement benefits from 2011 to 2021 (not including executive chairs) and found that only 4 percent of transitions mentioned these benefits.

If the outgoing CEO is becoming or continuing as board chair, the board needs to establish a strong rationale for the role and to clarify responsibilities and decision rights vis-à-vis the new CEO. It’s also important to set compensation that is appropriate for the level of involvement. Former CEOs typically receive cash at 50 to 80 percent of what they earned previously. If the board expects the role to last longer than a year, it might issue new equity awards at a reduced level, although practices are varied. Previously granted awards, in any case, continue to vest during the period. Some departing CEOs take on short-term consulting arrangements, typically for up to a year and rarely for more than a few years. Here as well, the board needs to define expectations and set the consulting rate accordingly.

An even bigger question is the compensation for the new CEO. Should you pay the new leader the same as the predecessor? The latter most likely was in place for several years before leaving, while the successor is new to the role and therefore may merit less pay initially. An external benchmarking exercise can help to determine competitive pay levels.

The board’s decision should be based on many factors, including demonstrated performance, current role, and pay prior to promotion. The board could choose to go to a median level right away or set a plan to get there over two to three years. If the new CEO comes from outside and has relevant experience, the pay package might be close to the predecessor’s from the start. In some cases it might even be higher, given the executive may need to move to a new location and disrupt their family. Note that external hires may be more expensive as they may expect a risk premium for making the move. External hires also expect to be made whole for equity forfeited in leaving their former employers.

One-time awards to the new leader may make sense but need to be handled carefully with an eye on external reactions. Proxy advisors and shareholders are skeptical of front-loaded awards given the risk of overpayment and the potential lack of alignment between pay and performance. To help mitigate this concern, boards can tie the awards to substantial performance conditions and vesting, while adding shareholder-friendly terms such as forfeiture upon termination or nonperformance and a clawback.

Boards should consider including a larger team of leaders in any one-time award, since it is typically a team effort to achieve step-change goals. In all of these discussions, boards should remember that compensation is most powerful when it aligns with both the company’s culture and the leader’s priorities.

This is also the time to think again about the rest of the C-suite. The incoming CEO will largely pick or confirm the team, but boards should also be involved to make sure people are in the right roles. Are there any executives that the new leader must keep? Are the pay levels appropriate, especially for people with new roles or responsibilities? As before, we advise caution with retention grants, which in any case should be attached to performance.

We’ve seen these dynamics play out in many companies. A large health-care company had a smooth transition with an internal successor and no change in strategy. The departing CEO became board chair at 80 percent of previous compensation and with no equity grant. The new CEO initially received compensation of roughly 90 percent of the former CEO’s at target. The board also nominated an independent director as lead director with a significant role, paying them at the high end of the market. The board went on to review pay levels for the remaining C-suite, with aggressive increases for those executives that the CEO hoped would stay. By contrast, at a food service company the board terminated the CEO and brought in a leader from a comparably sized organization to turn around the company. The board paid this first-time CEO equal to the predecessor to lure the new leader to the role and to acknowledge the turnaround required. An existing board member became chair with the intent to coach and provide support, for which the new chair gained a premium above the regular board pay. The new CEO expected to replace many current executives but wanted a strong operating partner, so the board gave a substantial retention award to the head of operations.

Still, boards need to pay attention to the rationale for special awards. At a consumer-packaged-goods company the board hired from outside with a substantial equity award tied to improving stock price. The two losing internal candidates received large, time-based retention awards. Investors criticized these arrangements because they did not appreciate the rationale. The board reached out to shareholders to get detailed feedback, clarify the rationale, and redesign future compensation awards to better align with strategy.

PHASE FOUR: POST-SUCCESSION

After the general announcement, the board still has work to do. Besides the required disclosure on Form 8-K, any employment agreement or pay awarded outside of preexisting programs must be disclosed on an 8-K within four business days of the new CEO signing on. Equity grants are reportable on Form 4 within two business days.

Whether to disclose more depends on the board’s judgment. The board may need to follow up with investors on compensation if the arrangements have changed considerably from the past or have one-time elements. This messaging is often best addressed with direct outreach meetings focused on communicating specific messages.

Internal messaging is equally important. The board can work with the former and new CEOs to develop the key communication points. Directors might also engage in one-on-one conversations with key executives who might be sensitive about the decisions on promotion or pay.

The board also needs to confirm alignment with the new CEO on expectations and priorities and areas of focus. After all, even in smooth transitions, a new CEO brings new perspectives, a different management style, and updated strategic priorities. Alignment is especially important when the board is looking for a substantial turnaround or step-change, which often involves a leader coming from outside. Changes to incentive compensation can be particularly powerful in messaging change and creating alignment among leaders and broader management. Well-designed incentive programs can add urgency to strategic priorities while offering opportunities to create wealth if shareholders benefit from new objectives being achieved.

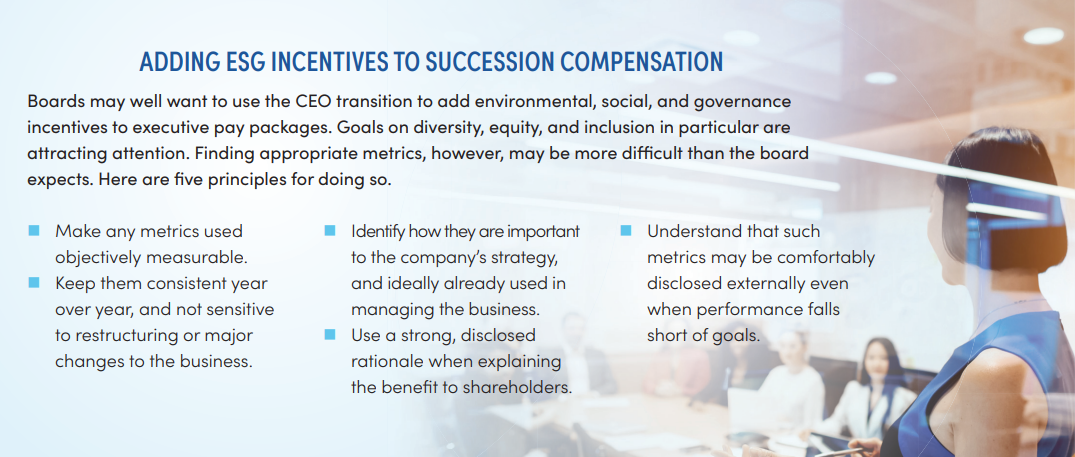

When redesigning incentive plans, in addition to financial goals, the board should discuss operational and strategic goals, including environmental, social, and governance (ESG) and human capital management goals, with the CEO (see sidebar). Succession is a good time to add or revisit these goals and consider whether they are critical to new strategic priorities and therefore should be linked to incentive plans. Once the succession plan is in place and the new leader has settled in, the board can return to phase one and begin planning for the next succession.

SUCCESSION AND COMPENSATION INTERTWINE

CEO transitions involve challenge and possibilities, letting go of the old and imagining the new. These can be exciting times for boards, even with the added internal and external scrutiny, as long as they’ve done the advance work of succession planning. Broad adjustments in executive compensation can be vital to the process, as candidates are groomed and tested, before the announcement, and as the new leader settles into place. A CEO transition doesn’t happen in isolation. The process affects not just the likely candidates but all key contributors seeing the change affecting their own prospects. Changes at the top can alter a great many individual roles throughout the organization.

As in other times of transition, pay programs can deviate from the norm, but boards will need explanations for internal as well as external stakeholders. Stretch responsibilities can justify new compensation packages and special awards not just for the incoming CEO but across the senior team. A planful approach, one that gets ahead of communications, can ease acceptance. With CEO succession no longer an occasional event, boards are turning their efforts into an ongoing process. Compensation is an essential part of that planning.

Print

Print