Lisa, an elementary school teacher from Ambler, Pa., came home from work one day and said to her husband, “Honey, guess what? I landed that summer teaching position I wanted!” “Wow, congratulations!” he replied. “I know how hard you worked to get that job. I am so happy for you! You must be really excited.” The way Lisa's husband reacted to her good news was also good news for their marriage, which, more than 20 years later, is still going strong; such positive responses turn out to be vital to the longevity of a relationship. Numerous studies show that intimate relationships, such as marriages, are the single most important source of life satisfaction. Although most couples enter these relationships with the best of intentions, many break up or stay together but languish. Yet some do stay happily married and thrive. What is their secret?

A few clues emerge from the latest research in the nascent field of positive psychology. Founded in 1998 by psychologist Martin E. P. Seligman of the University of Pennsylvania, this discipline includes research into positive emotions, human strengths and what is meaningful in life. Positive psychology researchers have discovered that thriving couples accentuate the positive in life more than do those who stay together unhappily or split. They not only cope well during hardship but also celebrate the happy moments and work to build more bright points into their lives.

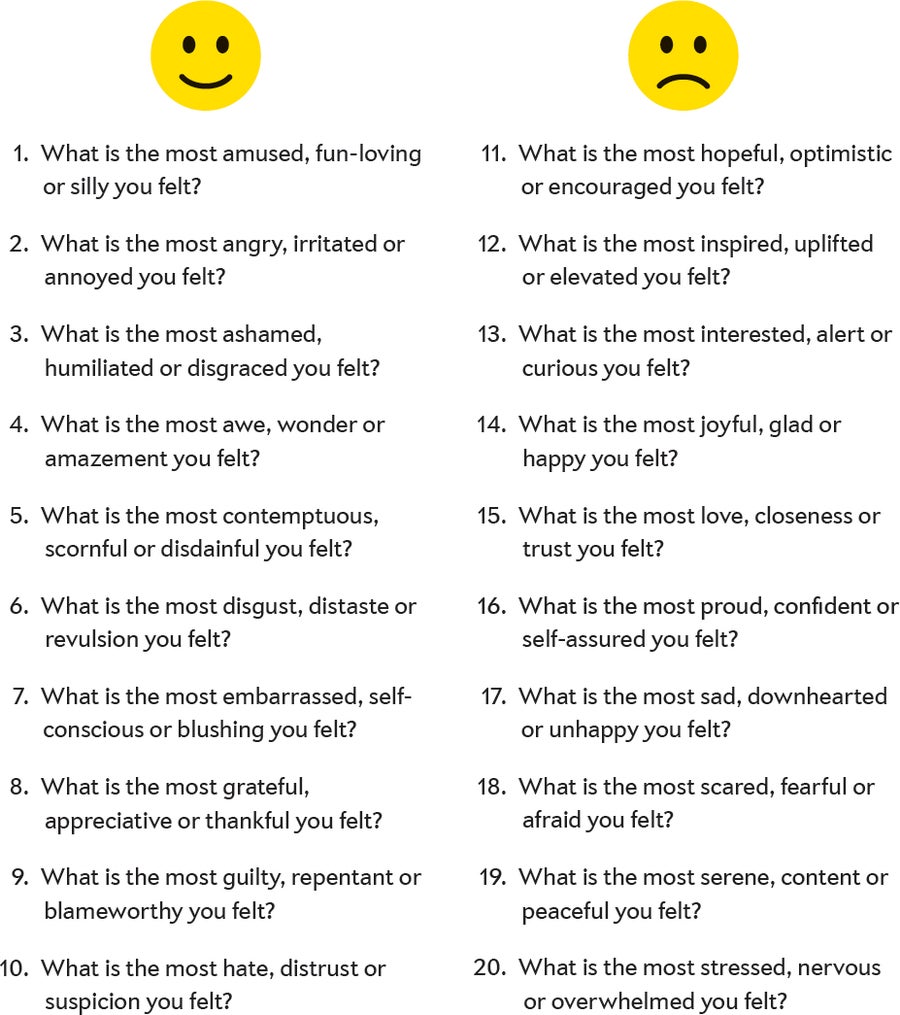

It turns out that how couples handle good news may matter even more to their relationship than their ability to support each other under difficult circumstances. Happy pairs also individually experience a higher ratio of upbeat emotions to negative ones than people in unsuccessful liaisons do. Certain tactics can boost this ratio and thus help to strengthen connections with others. [To measure your positivity ratio, see “How Positive Are You?” below.] Another ingredient for relationship success: cultivating passion. Learning to become devoted to your significant other in a healthy way can lead to a more satisfying union.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Let the Good Times Roll

Until recently, studies largely centered on how romantic partners respond to each other's misfortunes and on how couples manage negative emotions such as jealousy and anger—an approach in line with psychology's traditional focus on alleviating deficits. One key to successful bonds, the studies indicated, is believing that your partner will be there for you when things go wrong. Then, in 2004, psychologist Shelly L. Gable, currently at the University of California, Santa Barbara, and her colleagues found that romantic couples share positive events with each other surprisingly often, leading the scientists to surmise that a partner's behavior also matters when things are going well.

In a study published in 2006 Gable and her co-workers videotaped dating men and women in the laboratory while the subjects took turns discussing a positive and negative event. After each conversation, members of each pair rated how “responded to”—how understood, validated and cared for—they felt by their partner. Meanwhile observers rated the responses on how active-constructive (engaged and supportive) they were—as indicated by intense listening, positive comments and questions, and the like. Low ratings reflected a more passive, generic response such as “That's nice, honey.” Separately, the couples evaluated their commitment to and satisfaction with the relationship.

Mutual support and enthusiasm in good times are essential to a successful relationship, according to the latest research in positive psychology. Passive responses to exuberant announcements indicate a lack of interest—and are almost as damaging to a relationship as directly disparaging a partner’s good news. Credit: Age Fotostock (1); © iStock.com (2)

The researchers found that when a partner proffered a supportive response to cheerful statements, the “responded to” ratings were higher than they were after a sympathetic response to negative news, suggesting that how partners reply to good news may be a stronger determinant of relationship health than their reaction to unfortunate incidents. The reason for this finding, Gable surmises, may be that fixing a problem or dealing with a disappointment—though important for a relationship—may not make a couple feel joy, the currency of a happy pairing.

In addition, couples who answered good news in an active-constructive way scored higher on almost every type of measure of relationship satisfaction than those who responded in a passive or destructive way. (Passive replies indicate a lack of interest, as in changing the subject, and destructive responses include negative statements such as “That sounds like tons of work!”) Surprisingly, a passive-constructive response (“That's nice, honey”) was almost as damaging as directly disparaging a partner's good news. These data are consistent with an earlier study showing that active-constructive responders experience fewer conflicts and engage in more fun activities together. These individuals also are more likely to remain together. Active-constructive responding shows that a person cares about why the good news is important, Gable says, conveying that you “get” your partner. Conversely, negative or passive reactions signify that the responder is not terribly interested—in either the news or the person disclosing it.

Thankfully, life affords many opportunities to respond supportively to optimistic announcements: Gable, along with social psychologist Jonathan Haidt, now at New York University Stern School of Business, reported in 2005 that, for most individuals, positive events happen at least three times as often as negative ones. And just as responding enthusiastically to your partner's good news increases relationship satisfaction so does sharing your own positive experiences. In a daily diary study of 67 cohabiting couples published in 2010 in Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, Gable found that on days when couples reported telling their partner about a happy event they also reported feeling a stronger tie to their partner and greater security in their match.

Power of Positive Emotions

Reveling in the good times boosts the positive emotions of both members of a couple. Three decades ago positive psychology pioneer Barbara L. Fredrickson of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill showed that positive emotions, even fleeting ones, can broaden our thinking and enable us to connect more closely with others. Having an upbeat outlook, she argues, enables people to see the big picture and avoid getting hung up on small annoyances. This wide-angle view often brings to light new possibilities and offers solutions to difficult problems, making individuals better at handling adversity in relationships and other parts of life. It also tends to dismantle boundaries between “me” and “you,” creating stronger emotional attachments. “As positivity broadens your mind, it shifts your core view of people and relationships, bringing them closer to your center, to your heart,” Fredrickson says.

When a person's positive sentiments outnumber negative feelings by three to one, that individual tends to become more resilient in life and love, Fredrickson found. Among individuals in enduring and mutually satisfying marriages, ratios tend to be even higher, hovering around five to one, according to research by world-renowned marriage expert John Gottman, emeritus professor of psychology at the University of Washington.

In her book Positivity (Crown, 2009), Fredrickson lists the 10 most frequent positive emotions: joy, gratitude, serenity, interest, hope, pride, amusement, inspiration, awe and love. Although all these emotions matter, gratitude may be one of the most important for relationships, she says. Expressing gratitude on a regular basis can help you appreciate your partner rather than taking his or her small favors or kind acts for granted, and that boost in appreciation strengthens your relationship over time.

In a study published in 2010 in Personal Relationships, social psychology researcher Sara B. Algoe, also at U.N.C. Chapel Hill, and her colleagues asked cohabiting couples, 36 percent of whom were married or engaged, to report nightly for two weeks how grateful they felt toward their partners from their interactions that day. In addition to gratitude, they numerically rated their relationship satisfaction and their feelings of connection with their partner. On days that people felt more gratitude toward their partner, they felt better about their relationship and more connected to him or her; they also experienced greater relationship satisfaction the following day. Additionally, their partners (the recipients of the gratitude) were more satisfied with the relationship and more connected to them on that same day. Thus, moments of gratitude may act as a booster shot for romantic relationships.

The fact that gratitude affected both partners also hints that expressing your gratitude is important for relationship satisfaction. To test this idea directly, Algoe, Fredrickson and their colleagues asked people in romantic relationships to list nice things their partners had done for them lately and to rate on a scale from 1 (not at all) to 7 (very much) how well they thought they had expressed appreciation to their partner for having done those favors. The researchers found that each unit improvement in expressed appreciation decreased by half the odds of the couple breaking up in six months.

Promoting Passion

Like gratitude, feelings of passion can strengthen our bonds with others. Many people equate passion with a desperate longing, suggested by song lyrics such as “I can't live without you” and “You're my everything.” But such unbridled or obsessive passion is not conducive to a healthy relationship, according to work by social psychologist Robert J. Vallerand of the University of Quebec at Montreal. On the contrary, obsessive passion—a type that seems to control you—is as detrimental to the relationship, making it less satisfying sexually and otherwise, as having no passion.

A healthy passion—a voluntary inclination toward an activity or person whom we love and value—does provide benefits, however. It is associated with relationship satisfaction and constructive behavior during tough times, whereas obsessive passion predicts destructive behavior during conflicts and breakups over time. Using the Romantic Passion Scale, a questionnaire that measures harmonious and obsessive passion, Vallerand found that harmonious passion helps couples relate better, in part by enabling them to become intimate with their partner while maintaining their own identity, which helps to foster a more mature partnership. Their intimacy enables them to continue to pursue their own hobbies and interests rather than subjugating their own sense of self to an excessive attachment to the other person. (Previous research by Vallerand and his colleagues revealed that harmonious passion for activities leads to cognitive and emotional advantages, such as better concentration, a more positive outlook and better mental health. No one has yet studied whether these benefits spill over to our romantic relationships, however.)

You can cultivate healthy passion by joining your partner in a pursuit that both of you enjoy, Vallerand suggests. Engaging in exhilarating activities with another person has been shown to boost mutual attraction. Avoid serious competition because the point of the outing should not be winning but enjoying time together. Another tip: write down and share with your partner some of the reasons why you love him or her and why your relationship is important.

Positive Steps

Experts also have tips for injecting positive emotions into your life. First, learn to respond constructively to your partner's positive declarations. Look for opportunities to express your interest, support and enthusiasm. Acknowledge a terrific presentation at work, say, or faster time in a road race. Ask yourself regularly: “What good news has my partner told me today? How can we celebrate it?” Affirm your partner's joy first. Discuss your concerns, such as the practical downsides of a promotion, at a later time. In addition, be attentive and actively participate in the conversation. Ask questions and indicate interest nonverbally: maintain eye contact, lean forward and nod. To show you heard, rephrase a part of what he or she said, for instance: “You seem really excited about this new job.”

Simply willing ourselves to feel positive emotions is not effective. In fact, valuing happiness too much may even backfire. Instead Fredrickson emphasizes the importance of taking action to “prioritize positivity.” In other words, making choices and organizing our lives in ways that we are more likely to experience positive emotions. People who prioritize positivity have greater psychological resources such as resilience and self-compassion. Schedule exuberant feelings into your day by, say, making time for activities that evoke such emotions. Locate places you can walk to quickly to connect with nature or other beautiful scenery. Make these places regular destinations for exercising, reflecting or hanging out with friends. In addition, practice savoring a genuine source of positive emotion that is currently, has been or will be a part of your life.

Another idea for raising your personal positivity score: create a “positivity portfolio,” a collection of meaningful mementos signifying a positive emotion. For example, you might encapsulate joy by creating a collage of uplifting song lyrics and pictures that make you smile. Looking at your creation every day for 20 minutes can improve your positivity score. Try infusing fun or pleasure into mundane tasks. For instance, transform dinner preparation into a family activity in which the kids help by measuring ingredients and slicing vegetables, Fredrickson says. Turn daily challenges or snafus, like your child's misplaced shoes, into a game to see who can find them first.

Look for opportunities to thank your partner. “Try highlighting those small moments in which your partner has been thoughtful and expressing it to him or her,” Fredrickson suggests. And find time each day to share something positive that has happened to you.

How Positive Are You?

Although all healthy relationships involve some negative feelings, positive emotions form the foundation of any strong pairing. Psychologist Barbara L. Fredrickson of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill found that individuals who thrive in and outside relationships tend to experience a ratio of three or more positive emotions for every negative one in their daily lives. To find out how you compare, take the following quiz, called the Positivity Self Test, developed by Fredrickson in 2009.

Instructions

Using the scale below, indicate the greatest degree to which you have experienced each of the following emotions during the previous 24 hours.

0 = Not at all

1 = A little bit

2 = Moderately

3 = Quite a bit

4 = Extremely

Scoring

Circle questions 1, 4, 8, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16 and 19 and then underline questions 2, 3, 5, 6, 7, 9, 10, 17, 18 and 20.

Count the number of circled (positivity) questions you rated 2 or higher and the number of underlined (negativity) questions you scored 1 or higher.

Divide your positivity tally by your negativity tally. (If your negativity tally is zero, replace it with a 1.) The result represents your positivity ratio for today.

If you scored below 3:1, as most Americans do, you may be able to raise that ratio with exercises recommended in this article and in Fredrickson's book, Positivity (Crown, 2009). Because this test provides a mere snapshot of your feelings during the previous 24 hours, you may also want to repeat it nightly for two weeks to gain a more reliable assessment of your positivity ratio.

For more details as well as for a convenient way to test yourself, visit www.positivityratio.com.