The New Old-School Birth Control

Tracking fertility effectively is more complicated than just counting days on the calendar. But it can work.

If recent trend stories are to be believed, such as one from Ann Friedman at New York Magazine, some heterosexual women—particularly those in long-term, monogamous relationships—are giving up on the default birth control options. Synthetic hormones come with side effects, condoms don’t feel great, intrauterine devices are kind of scary. And so they turn to what seems to be the only method left for avoiding pregnancy: “pulling out.” A study by Duke University Medical Center resident Dr. Annie Dude found that 31 percent of women ages 15 to 24 had relied on the withdrawal method at least once.

Except that pulling out isn’t the only natural method of contraception. Some women have dispensed with not only the pill, but also the whole black-box approach to their reproductive systems, by learning how to carefully gauge when they’re fertile so they and their partners can decide when to have sex, and with what level of protection. There is a good amount of research and educational programs devoted to natural fertility awareness-based methods of birth control (FABM), though they may not yet be well-known.

A scant 1 to 3 percent of women in the U.S. use FABM as their contraception of choice, according to a 2009 study from the University of Iowa. But more want it, even if they don’t quite know what to call it: surveys conducted by physicians at the University of Utah show that when natural fertility-awareness methods are described to women, 25 percent say they would strongly consider using one as their means of birth control. But thanks to its glaring image problem and a set of just-as-formidable infrastructural hindrances, ignorance of fertility awareness-based methods is widespread. If more women looking for a non-hormonal, non-barrier, non-surgical form of birth control knew about FABM, then more of them could be practicing it to its utmost effectiveness—rather than doing it in the dark.

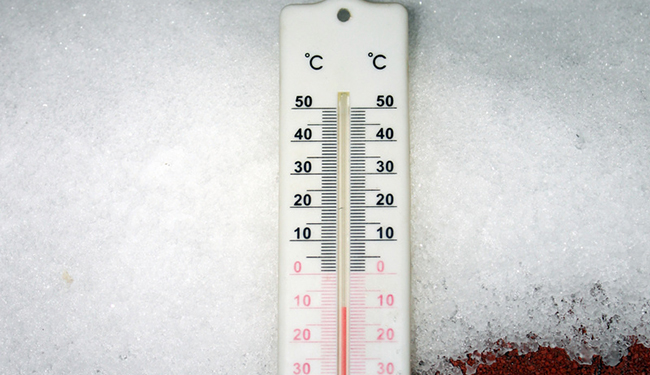

These fertility awareness models actually can work, and work well. A recent 20-year German study asked 900 women to track their fertility every day by monitoring their body temperature and cervical mucus, and use that information to avoid pregnancy. The study’s researchers found this to be 98.2 percent effective—comparable with the pill, and a far cry from the 82 percent effectiveness rate of the withdrawal method.

In January, a group of physicians organized through the Family Medicine Education Consortium published a review looking into the efficacy of various FABMs. They combed through all the relevant research published since 1980, and concluded that “when correctly used to avoid pregnancy, modern fertility awareness-based methods have unintended pregnancy rates of less than five (per 100 women years).” (A woman year is one year in the reproductive life of a woman.) Their effectiveness levels, in other words, are “comparable to those of commonly used contraceptives,” the study’s authors add.

Modern fertility-awareness methods are rooted in an ever-improving understanding of the various subtle signs a woman’s body flashes to indicate it’s in prime baby-making mode. Some FABMs teach women how to chart cervical mucus secretions—and their changes in quantity and texture—to figure out when she’s fertile. Other approaches add the requirement that practitioners record their daily basal body temperature. Still others combine mucus observations with technology that picks up on hormones associated with fertility in urine.

The downside is that all FABM methods require in-person training, generally multiple sessions (reading a book or consulting a website or an app doesn’t quite cut it). Plus, the few minutes it takes to measure and chart symptoms each day makes the methods much more user-dependent than all of the more popular forms of contraception.

The distinction between these newer versions of FABM and older vintages, like the outmoded rhythm method, which has women count days on a calendar rather than look for bodily signs of fertility, can be lost on the uninformed. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s periodic contraception report, for example, lumps together all natural approaches—including the rhythm method—and stamps them with a damning 24 percent failure rate. (A full 86 percent of the natural-method users surveyed for that report, in fact, said that rhythm was their go-to model.)

But this is the least of FABMs’ obstacles to wider adoption. A much more complicated tangle of factors must be called up in explaining this paradox in which a sizable proportion of women have expressed a desire for a viable birth control option that practically no one uses.

There’s the obvious image problem, for a start. FABM is the secular branch of a much older—and thoroughly Catholic—tree called Natural Family Planning (NFP). Like FABMs, NFP methods also teach cervical mucus observation and temperature-taking, but they preach abstinence during fertile times, so that a couple never has to use any barrier methods like condoms, diaphragms, or spermicide. FABMs generally advise the use of two barrier methods if a couple decides to have sex while the woman is most fertile.

Thanks in part to these origins, people may immediately assume religious ties when they come across research or programs promoting natural fertility-awareness, which can lead to a quick, wholesale dismissal. Contributing to this perception is the fact that in any search for teachers or certification programs in fertility awareness it’s several times easier to find those connected to NFP than to the secular version. Ilene Richman, director of the Fertility Awareness Network, North America’s only professional organization for secular instructors of fertility awareness, says the NFP listserv she subscribes to has 300 members; her own FAN list has 30. The extensive network of Catholic volunteers teaching NFP within their parishes simply has no match on the secular side, she says.

“There’s no secular equivalent of a church that [prospective FABM teachers] can go to and get support for this,” Richman says. “I can’t tell you how many inquiries I get [from people who want to teach]; probably one or two a week. It would be nice to say, ‘Take this accredited class that’s offered nationally,’ but I can’t.” The resulting imbalance has perpetuated the sense among many in the U.S. that no one practices fertility awareness except for the religiously motivated.

Recognizing that this uniformly Catholic face is likely hindering adoption of FABMs., a group of physicians gathered in 2010 to found the Fertility Appreciation Collaborative to Teach the Systems (FACTS), which aims for a science-first approach to getting information about fertility awareness in front of the country’s physicians. FACTS is part of the Family Medicine Education Consortium and is staunchly secular in its funding affiliations, though its members run the gamut—the core coalition includes Georgetown University professor Marguerite Duane, a Catholic who doesn’t prescribe the birth control pill to her patients, and Richman, who is not religious in her approach to FABM and says she simply wants to spread the word about “the full spectrum of informed choice.” FACTS’ main source of funding is the March of Dimes, but Duane says it’s a notoriously difficult space in which to find funding, especially when a group is committed to remaining secular in its ties. The federal government has devoted some funding to the research and teaching of natural birth control methods, but the vast majority of it has gone through USAID, the agency charged with administering civilian aid to developing regions overseas, and the specific fertility awareness methods and programs it’s developed have been tailored to those populations. And, of course, FABMs don’t offer the type of economic opportunity that many companies see in pills, rings, and patches.

“The problem is that there’s not a large pharmaceutical company behind this to make it extremely well known,” says Victoria Jennings, director and principal investigator at Georgetown University’s Institute for Reproductive Health. “When you look at the incredible amount of resources pharmaceutical companies spend on trainings and updates and so forth for clinical family planning providers, you see it’s not a level playing field.”

This lack of resources means that fertility awareness-based options often don’t register on the radars of physicians, let alone their patients. A FACTS survey of 120 family medicine residency programs found that more than half of women’s health faculty members were not familiar with modern FABMs, and 25 percent of these residency programs did not include the methods in their women’s health curriculum.

“It’s interesting,” says Mihira Karra, chief of the research, technology and utilization division in USAID’s office of population and reproductive health, “with all the other methods [besides fertility awareness], it’s usually at the client level where there are misperceptions that we try to overcome. With the natural methods, it’s the reverse; we have clients eager to use them, but our big barriers are sitting at the higher medical, policy, and programming levels.”

To remove those barriers, rather than shrugging and accepting the one in five chance of accidental pregnancy that the withdrawal method offers, women and their partners could make an informed inquiry into whether a FABM would be a better option for them.

“Until there is some kind of commitment on the part of the medical community and OB-GYNs to actually provide women the full range of options regardless of whether or not it is something that can be commodified or sold, this is always going to be at a disadvantage,” Richman says.