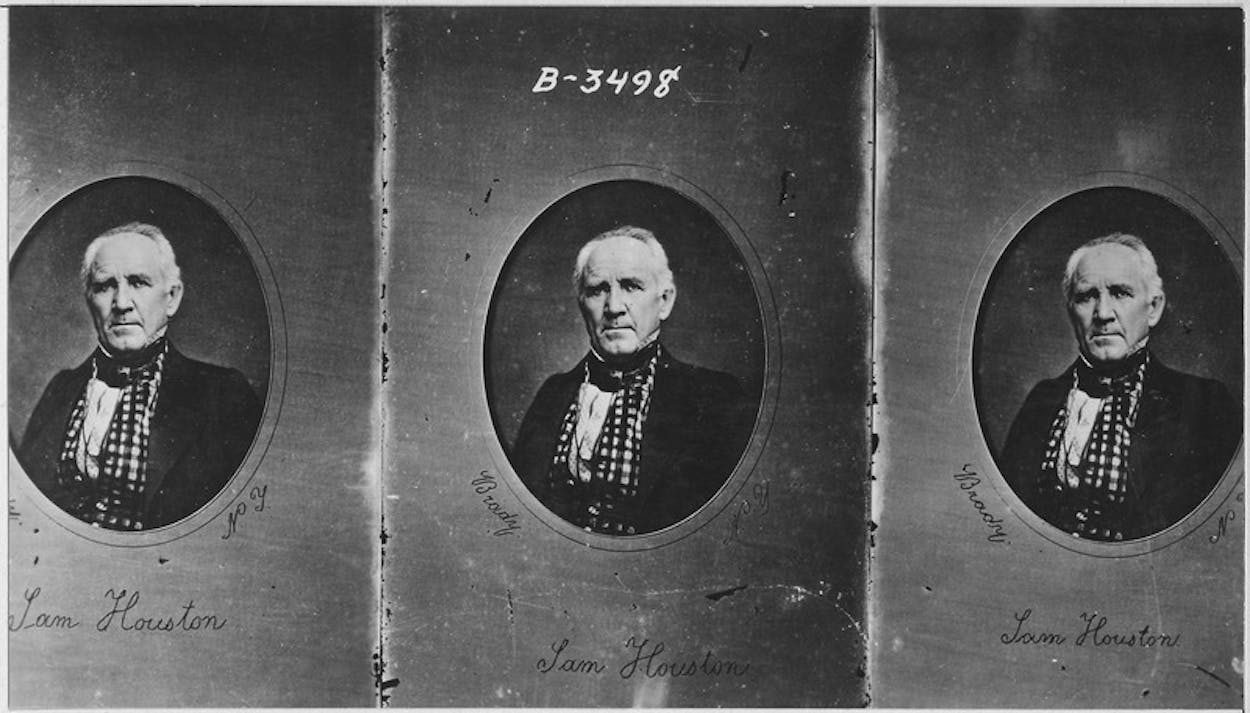

“Damned rascal!” — Sam Houston just before he thrashed Congressman William Stanbery.

Angry chest bumping and a shove or two are not unusual toward the end of a Texas Legislature, but this year’s end of session confrontation between several Democratic legislators and a Republican colleague was perhaps the most dramatic since one senator sucker punched another during a 1985 filibuster on a bill to regulate the shrimping industry. Even that kerfuffle—which erupted not over contentious shrimping regulations but from an exchange of personal insults—did not compare to this year’s exchange, which ultimately resulted in a death threat. But historic parallels can be tempting, and though our recent incident was less violent, we couldn’t overlook the similarities to the run-in that prompted Sam Houston to make his history-changing move to Texas in 1832.

Texas Capitol, May 29, 2017

Protestors from across the country arrived at the Texas Capitol wearing red to show opposition to the state’s new “sanctuary cities” law, known as Senate Bill 4. The law will punish law enforcement officials who do not cooperate with Immigration and Customs Enforcement when it comes to detainer requests for undocumented immigrants. It also allows police to question anyone who is detained or arrested about their citizenship and residency status. About a week before the protest, a national call for volunteers went out in the left-leaning magazine the Nation: “Spread the word on social media. Use the hashtag #SB4isHate and let your friends and family know what’s going on.”

About 500 of the protestors, uniformly decked in red, entered the Texas House gallery last Monday and started yelling and taunting the legislators. State Representative John Cyrier, serving as the presiding officer, ordered the Texas Department of Public Safety to clear the gallery. Officers started peacefully ejecting the protestors while the red-clad masses chanted, “Hey, hey, ho, ho, SB 4 has got to go.”

U.S. House Chamber, March 31, 1832

Congressman William Stanbery of Ohio, an opponent of then-President Andrew Jackson, questioned the president’s integrity from the House floor. An opponent of Jackson’s Indian Removal Act, Stanbery repeated allegations that Sam Houston, as governor of Tennessee, had been involved in a scheme to defraud Cherokee tribe. Houston, of course, was friends with the Native Americans and tried to protect them from scams. The rumor was a lie, but Houston could not sue Stanbery for slander because the congressman was protected by congressional privilege. Angry, Houston promised to beat an apology out of Stanbery. Stanbery started carrying pistols for self-defense.

Texas House Chamber, shortly after noon, May 29, 2017

Republican state Representative Matt Rinaldi of Irving approaches a group of Latino lawmakers, waving a cell phone while saying he had called Immigration and Customs Enforcement to come arrest undocumented immigrants in the crowd.

“F— them, I called ICE,” one of the Hispanic lawmakers recalled Rinaldi as saying. Rinaldi later denied using the profanity.

The Hispanic lawmakers saw it as insulting racial profiling, because not all the people in the crowd were undocumented immigrants. “He looked into the crowd, and he saw illegals. Whether he wants to accept it or not, he has hate in his heart for those people and wants to see them gone,” said Representative Ramon Romero Jr.

Representative César Blanco of El Paso reminded Rinaldi, who is Italian-American, that the “Irish and Italians were persecuted in the same way.” “Yeah, but we love our country.” Rinaldi responded.

Then the scuffle began. “He wanted a fight. He got a fight,” said Representative Philip Cortez of San Antonio. Several Hispanic lawmakers started shoving Rinaldi.

Pennsylvania Avenue, a half mile from the U.S. Capitol, about 8 p.m., April 13, 1832

Stanbury exited his boarding house with a pistol in his pocket and suddenly chanced upon Houston, whose only weapon was a walking stick made of young hickory. Because they did not know each other on sight, Houston asked if he was Stanbery. The congressman bowed and politely answered, “Yes, sir.”

“Then you are a damned rascal,” Houston declared, walloping Stanbery with his cane. The Ohioan stepped backward, throwing his hands over his head. His hat fell off and he pleaded, “Oh, don’t!”

Texas House Chamber, May 29, 2017

Several white lawmakers stepped between a group of about five Hispanic legislators and Rinaldi to keep the argument from escalating. For most, the path to Rinaldi was blocked, but Representative Poncho Nevárez side-stepped around the barrier of lawmakers around Rinaldi and started shoving him backward. Once. Twice. Three times.

“He’s lucky that there were more people around—because, while there was pushing and shoving, and anything beyond that isn’t acceptable and it shouldn’t happen out there, and I’m sorry it happened—the fact is he was asking for it,” Nevárez said.

Several Hispanic lawmakers said Nevárez indicated they should “take it outside” and Rinaldi responded by saying, “I’ll put a bullet in your head.” Rinaldi later issued a statement, giving his side of the exchange: “During that time, Poncho told me that he would ‘get me on the way to my car.’ He later approached me and reiterated that ‘I had to leave at some point, and he would get me.’ I made it clear that if he attempted to, in his words, ‘get me,’ I would shoot him in self defense.”

U.S. House, April 23, 1832, trial of Sam Houston for contempt of Congress

Senator Alexander Buckner of Missouri testified about the aftermath when Houston first caned Stanbery: “Houston continued to follow him up, and continued to strike him. After receiving several blows, Stanbery turned, as, I thought, to run off. Houston at that moment sprang upon him in the rear. Stanbery’s arms were hanging down, apparently defenseless. He seized him and attempted to throw him, but was not able to do so. Stanbery carried him abound on the pavement some little time … Stanberry fell; when he fell, he still continued to halloo, indeed he hallooed all the time pretty much, except when they were scuffling.”

Then Stanbery offered his side of the story. “I got my hand in my pocket and got my pistol and cocked it,” he testified. “I watched an opportunity while he was striking me with great violence, and pulled the trigger, aiming at his breast, the pistol did not go off.”

Buckner continued: “By this time, a crowd had gathered round and some person I do not know who spoke to Houston, Houston replied, ‘that he attended to his business, and that he had chastised the damned scoundrel; if he had offended the law, he would answer for what he had done.’”

The U.S. House found Houston in contempt of Congress and sentenced him to stand in the well of the House and take a scolding from the Speaker.

Texas House, May 29, 2017

Hispanic lawmakers hold a news conference in the Speaker’s Committee Room to denounce Rinaldi. State Representative Joe Moody of El Paso asks to have the House General Investigating Committee look into the incident.

U.S. Circuit Court of Maryland, July 1832

Stanbery, dissatisfied with the ruling of Congress, sued Houston for assault. The court found Houston guilty and ordered him to pay $500. Rather than pay the fine, Houston moved to Texas. And, well, became a legend.

Several weeks after his pyrrhic victory in court, Stanbery was censured by the House for insulting the Speaker, and that fall he lost his bid for re-election. The Albany Argus of New York summed up the entire affair:

“It will be recollected that this charge against the gentleman thus honorably acquitted was made by the valiant Mr. Stanbery of Ohio. In what light will the public view the honorable member, now that his accusations have fallen to the ground? He has failed in every thing connected with these arraignments from the first to last; and although Gov. Houston has a fine to pay … we are much mistaken, if, with the exception of his personal rencontre with the man from Ohio, he does not stand infinitely higher than his opponent, in the general estimation.”