John R. Ablan, Philip O. Brandes, and Brian J. Massengill are partners at Mayer Brown LLP. This post is based on their Mayer Brown memorandum, and is part of the Delaware law series; links to other posts in the series are available here.

On January 3, 2022, the Delaware Court of Chancery issued an opinion denying motions to dismiss in In re Multiplan Corp. Stockholders Litigation, a stockholder action arising out of the completed business combination for Churchill Capital Corp III (“Churchill”), a special purpose acquisition company (“SPAC”), and Multiplan Inc. (“MultiPlan”). The court’s opinion has important implications for SPAC sponsors, directors, officers and other stakeholders because of its application of traditional Delaware corporate law concepts to a “deSPAC” business combination transaction. This Legal Update (i) summarizes the facts alleged by the plaintiffs in the case and the court’s conclusions; and (ii) provides key takeaways and practical considerations.

Background

Churchill’s IPO and Business Combination with MultiPlan

As with virtually all modern SPACs, Churchill consummated an initial public offering (“IPO”) without any business operations of its own and instead was formed for the sole purpose of searching for, and consummating a business combination with, an operating company; a process it had two years to complete following its IPO. In exchange for a purchase price of $10.00 per unit, investors in Churchill’s IPO received units comprised of one share of Class A common stock and one-fourth of a warrant to purchase one share of Class A common stock at a strike price of $11.50. Churchill deposited $10.00 per unit sold in the IPO into a trust account, and funds placed in the trust account generally could be released only (i) upon completion of a business combination or (ii) in the absence of a business combination having been completed within the two-year window, upon dissolution and, in such case, the funds, plus interest, would be returned to Class A stockholders.

In keeping with standard SPAC market practice, prior to consummating any business combination, Churchill was required to offer its Class A stockholders the opportunity to redeem their Class A shares in connection with the consummation of such business combination. The redemption price would equal the investor’s original $10.00 investment plus such investor’s pro rata share of any interest earned on the funds while held in the trust account.

Churchill’s founders received a “sponsor promote” in the form of shares of Class B common stock (also known as “founder shares”) and warrants sold in a private placement that closed concurrently with the SPAC’s IPO. The founder shares were purchased for a nominal price (in aggregate, $25,000) and the private placement warrants were purchased for an aggregate purchase price of $23 million, or $1.00 per warrant. Upon completion of a business combination, the founders’ Class B common stock would automatically convert into Class A common stock. Following the IPO, the founders’ Class B common stock represented 20% of Churchill’s total outstanding common stock. Churchill’s founders were led by Michael Klein who effectively controlled voting power with respect to the Class B shares, and thus Churchill, through a series of holding companies. According to the court, each of Churchill’s directors had prior connections to Klein or his affiliates and was compensated with membership interests in a sponsor holding company, indirectly receiving economic interests in Class B shares and private placement warrants.

Churchill consummated its IPO in February 2020, raising $1.1 billion and began its search for a target operating company with which to combine.

In July 2020, Churchill signed a business combination agreement with MultiPlan, a provider of data analytics technology and cost management solutions platform for the U.S. healthcare industry (the “Business Combination”). The Business Combination would result in MultiPlan becoming a wholly owned subsidiary of Churchill and effectively a publicly traded company. The Business Combination would be funded by the following sources:

- $1.1 billion released from Churchill’s trust account, net of any funds removed as a result of redemptions from Class A stockholders; and

- $2.6 billion of proceeds from a PIPE (private investment in public equity) transaction, in which investors were sold new shares of Class A common stock, warrants and convertible notes.

On the same day that Churchill’s board of directors approved the Business Combination, Churchill formally retained The Klein Group LLC as a financial advisor. The Klein Group was affiliated with Klein and allegedly received $30.5 million for its advisory services.

Prior to the stockholder meeting to approve the Business Combination, Churchill sent stockholders a proxy statement describing, among other things, the terms of the proposed Business Combination and providing detailed disclosures about MultiPlan’s business, financial condition, prospects and possible risks. The proxy statement further described the events leading up to the Business Combination, including the “extensive due diligence” conducted by Churchill on MultiPlan.

The proxy statement also described the redemption right afforded to Churchill’s Class A stockholders and stated that the redemption price would be approximately $10.04 per share. As of the record date for the stockholder meeting, Class A shares were trading at $11.09 per share.

Finally, the proxy statement also disclosed MultiPlan’s dependence on a single customer—its largest—for 35% of its revenues. Critically, however, the proxy statement did not disclose that the customer was UnitedHealth Group Inc. (“UHC”) or that UHC intended to create an in-house data analytics platform called Naviguard.

Naviguard would allegedly both compete with MultiPlan and cause UHC to move all of its key accounts from MultiPlan to Naviguard by the end of 2022. According to the plaintiffs, UHC had publicly discussed its plan for Naviguard in June 2020, one month before Churchill agreed to the Business Combination.

In October 2020, Churchill and MultiPlan consummated the Business Combination with the holders of approximately 8.7 million of the 110 million outstanding Class A shares electing to exercise their redemption rights and approximately 93% of the shares casting a vote doing so in favor of the Business Combination.

The Litigation

On November 11, 2020, an equity research firm published a report about MultiPlan discussing, among other things, UHC’s formation of Naviguard. MultiPlan’s stock price declined to $6.27 the following day. Plaintiffs filed complaints for putative class actions in March and April 2021. The cases were consolidated and an operative consolidated complaint was filed against Klein, certain other Churchill directors, officers, various affiliated entities and Churchill (now renamed MultiPlan Corporation). The consolidated complaint alleged, among other things, claims of breach of fiduciary duty by the defendants when they issued a materially false and misleading proxy statement that effectively impaired Class A stockholders’ informed exercise of their redemption and voting rights. In May 2020, the defendants moved to dismiss the complaint (i) for failure to plead demand futility and (ii) for failure to state a claim upon which relief can be granted.

On January 3, 2022, the court denied these motions except with respect to one officer (only as to one count) and with respect to MultiPlan Corporation itself.

The Court’s Legal Analysis & Conclusions

In ruling on the defendants’ motions to dismiss, the court was required to assume that all of the plaintiffs’ well-pleaded factual allegations were true and to draw all reasonable inferences in favor of the plaintiffs. In its ruling, the court described the crux of the plaintiffs’ claims as follows: “the defendants breached their fiduciary duties by prioritizing their personal interests above the interests of Class A stockholders in pursuing the merger and by issuing a false and misleading proxy, harming stockholders who could not exercise their redemption rights on an informed basis.”

Breach of Fiduciary Duty Claims—“Entire Fairness” as the Standard of Review

In Delaware, the court’s default standard of review for a breach of fiduciary duty claim is the “business judgment rule,” which is a presumption that in making a business decision, a corporation’s board of directors acted on an informed basis, in good faith and in the honest belief that the action was taken in the best interest of the corporation. Typically, once this standard is applied, a Delaware court will find for the directors as a court will not substitute its own judgment for the judgment of a corporation’s board of directors. However, absent certain procedural safeguards, such as independent board committees, the deferential “business judgment rule” standard will not apply in transactions presenting conflicts of interest. In conflicted situations, Delaware courts apply the “entire fairness” standard, which shifts the burden to the defendant directors to prove the fairness of the transaction.

The plaintiffs put forth, and the court accepted, two individually sufficient arguments as to why the “entire fairness” standard applied: (i) the Business Combination, including the right to redeem, was a “conflicted transaction,” and (ii) a majority of the Churchill board of directors was conflicted either because they were self-interested or because they lacked independence from Klein.

Conflicted Transaction

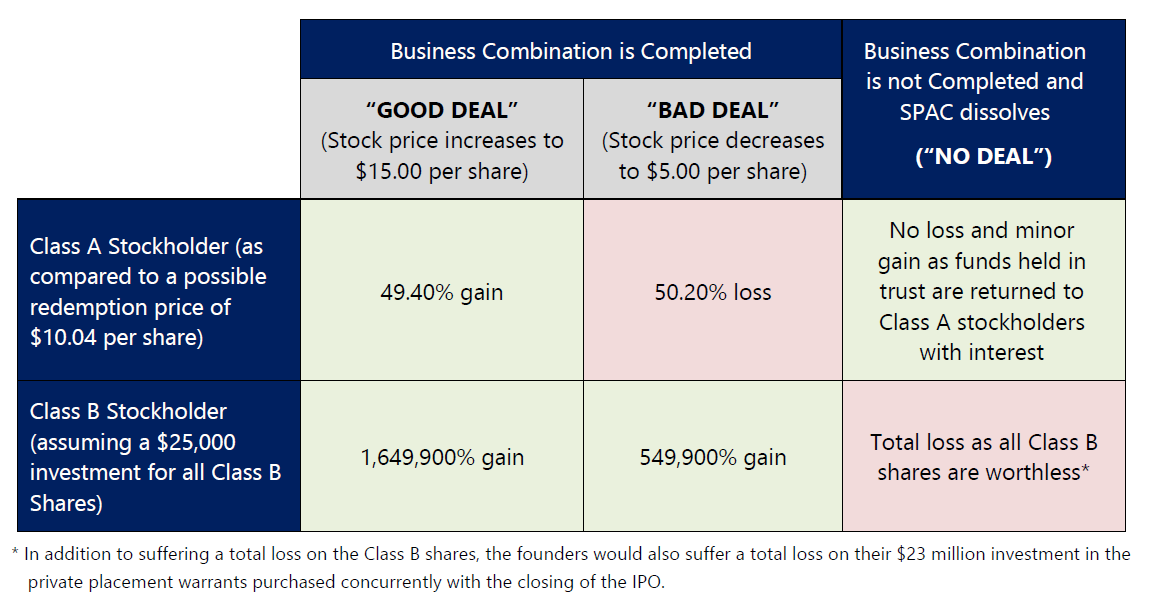

While the court acknowledged that the “entire fairness” standard was not triggered by Klein’s effective control of Churchill alone, the court concluded that the standard was required as a result of Klein and the other founders receiving a “unique benefit” from the Business Combination, a benefit not shared by the Class A stockholders. The “unique benefit” stems from the different financial incentives Class B stockholders had compared to Class A stockholders. The court observed that Class B stockholders stood to realize substantial gains even if the Business Combination was a “bad deal” and the post-combination company’s stock price fell dramatically, but would lose all of their invested capital if there was “no deal” and the SPAC dissolved. [1] In contrast, a Class A stockholder would realize substantial loss in a “bad deal” scenario but would get all of its capital back in a “no deal” scenario. The following table illustrates these differing incentives by summarizing the outcomes under different scenarios.

The defendants argued that the plaintiffs should not be able to use the differing economic incentives for Class A and Class B stockholders to challenge the Business Combination because these incentives were disclosed to them before they invested. The court rejected this argument and reasoned as follows:

In this case, the structure of the SPAC—and Klein’s incentives—were disclosed in the [IPO] prospectus but the transaction at issue was not. Public stockholders who invested in Churchill agreed to give the Sponsor an opportunity to look for a target company with the understanding that they retained an option to make a redemption decision. They did not, however, agree that they did not require all material information when the time came to make that choice. The defendants’ argument might be persuasive if it had been made about the [proxy statement] and the plaintiffs had opted not to redeem despite adequate disclosures—but that is not the universe alleged in the Complaint. [Emphasis added]

As a result, the court concluded that the plaintiffs’ “conflicted transaction” argument was sufficient to trigger the “entire fairness” standard.

Conflicted Board

In Delaware, if a majority of a corporation’s board of directors is self-interested or not independent with respect to a particular transaction, the “entire fairness” standard applies. In this case, the court concluded that the “entire fairness” standard was also applicable because all of Churchill’s directors were either self-interested in the Business Combination or not independent from Klein, the controlling stockholder, or both.

Using the stockholder meeting record date closing price of $11.09 per share, the plaintiffs estimated that Churchill’s directors (other than Klein) held interests in the founder Class B shares and warrants that had an implied market value that ranged from $3.3 million to $43.6 million. The court stated:

Delaware courts recognize that stock ownership by decision-makers aligns those decision-makers’ interests with stockholder interests; maximizing price. But, as discussed above, this argument ignores the diverging interests between insider Class B stockholders and public Class A stockholders lacking the benefit of full information when faced with the choice of a bad deal or liquidation.

The court illustrated the point with an example: even after a “bad deal” Business Combination (e.g., if the post-Business Combination company’s share price was $5.00), the court estimated that the directors holding the fewest amount of Class B shares would still hold shares worth over $500,000 (even after accounting for a significant discount rate for the 18-month lock-up and exclusion of unvested shares). The court concluded that “[a] greater than half-million-dollar payment is presumptively material at the motion to dismiss stage” and thus that court could “infer that a majority of directors were self-interested.”

Additionally, the court concluded that at least a majority of the directors were not independent of Klein. The court cited the following reasons: (i) Klein appointed each of the directors and had the unilateral power to remove them; (ii) most of the directors had the substantial financial incentives described above; (iii) several of the directors were beholden to Klein because he had appointed them as directors of other SPACs with the potential for more large paydays and may have been seeking future appointments; (iv) one of the directors was Klein’s brother; and (v) one of the directors was a managing director of another entity controlled by Klein.

While the court acknowledged that the actual extent of these relationships was not altogether clear at this stage in the litigation, the existence of these relationships was enough on a motion to dismiss to apply the “entire fairness” standard.

Breach of Fiduciary Duty Claims—Evaluation Using the “Entire Fairness” Standard of Review

Applying the “entire fairness” standard and presuming that the plaintiffs’ factual allegations were true, the court concluded that the complaint successfully stated a breach of fiduciary duty claim against Churchill’s directors.

Importantly, the court made clear that the viability of the plaintiffs’ claims was not due to the nature of the Business Combination or the resulting conflicts alone. As the court stated:

[The plaintiffs’ claims] are reasonably conceivable because the Complaint alleges that the director defendants failed, disloyally, to disclose information necessary for the plaintiffs to knowledgeably exercise their redemption rights. This conclusion does not address the validity of a hypothetical claim where the disclosure is adequate and the allegations rest solely on the premise that fiduciaries were necessarily interested given the SPAC’s structure. The core, direct harm presented in this case concerns the impairment of stockholder redemption rights. If public stockholders, in possession of all material information about the target, had chosen to invest rather than redeem, one can imagine a different outcome. [Emphasis added]

Key Takeaways & Practical Considerations

Although the court’s opinion is only a denial of a motion to dismiss and not a final ruling on the merits, it is an important development for SPACs and SPAC sponsors, directors and officers. The court’s conclusions signal potential increased litigation risk for SPAC directors in connection with business combination transactions. A very common feature of SPACs—the differing incentives for Class A versus Class B stockholders—may present an inherent conflict of interest requiring the application of the “entire fairness” standard to a deSPAC business combination transaction.

The following are some key takeaways and practical considerations these stakeholders would be well-advised to consider:

- SPAC sponsors should conduct an analysis of their SPAC’s board of directors and carefully consider the amount and type of compensation given to independent directors. SPAC sponsors should ensure that a majority of a SPAC’s directors do not have any material pecuniary interests in the SPAC or any employment, familial or other potentially problematic relationships with the sponsor or its affiliates. Any material pecuniary interests or potential conflicts of interest that do remain should be prominently disclosed in a SPAC’s proxy statement to approve a business combination.

- Sponsors with multiple SPACs should consider adopting a policy of appointing different independent directors for each such SPAC.

- If there are conflicts of interest among a SPAC’s directors, whether through significant ownership of Class B shares, private placement warrants or otherwise, and a SPAC expects the “entire fairness” standard to apply to litigation challenging its business combination, the SPAC should consider obtaining a fairness opinion from a financial advisor to support an analysis that the terms of the business combination are fair, from a financial perspective, to the SPAC’s Class A stockholders.

- In its opinion, the court holds that the plaintiffs’ claims are direct rather than derivative. Many fiduciary duty claims against directors are derivative, meaning such claims are initiated by stockholders on behalf of the corporation rather than directly against the directors. Derivative claims include procedural hurdles that make them more difficult to litigate than direct claims. In its opinion, the court allowed the plaintiffs to proceed on a direct claim because it concluded that the plaintiffs allegedly suffered harm independent of, and not shared with, the corporation. Unlike a claim for corporate waste or dilution, the court concluded that the plaintiffs suffered harm directly by the alleged impairment of their redemption rights. This conclusion is important because virtually all SPACs provide their Class A stockholders with redemption rights prior to consummating a business combination, and, as such, it appears that a SPAC’s structural features provide a path for stockholders to make direct claims against their directors for breaches of fiduciary duty.

- SPAC sponsors and SPACs must ensure that they conduct robust due diligence on a target operating company, both before signing a business combination agreement and up to and including the distribution of their proxy statement seeking stockholder approval for the deal. Conducting rigorous due diligence on a potential target is the best way to ensure that a SPAC’s proxy statement discloses all material information necessary to allow SPAC investors to make an informed investment decision in relation to a proposed business combination. The court’s opinion indicates that its analysis does not rest on the founders’ differing financial incentives and conflicts alone. Without the failure to include the disclosure on UHC and Naviguard, the MultiPlan court can “imagine a different outcome.”

- Insisting on fulsome due diligence on a potential target is consistent with statements made by the staff of the Division of Corporation Finance [2] of the Securities and Exchange Commission (“SEC”) and SEC Chairman Gary Gensler [3] that the gatekeeper/underwriter/due diligence function normally undertaken by an investment bank in a traditional IPO may fall to SPAC sponsors, directors and officers in a deSPAC transaction. According to Chair Gensler, “a lot of people think the term ‘underwriters’ solely refers to investment banks. The law, though, takes a broader view of who constitutes an underwriter.” Similarly, in its “Order Instituting Cease-And-Desist Proceedings” [4] against Stable Road Acquisition Corp. (“SRAC”), another SPAC, the SEC stated that SRAC’s failure to conduct adequate due diligence on its business combination target resulted in materially misleading materials being presented to investors. In that case, the SEC imposed monetary penalties on SRAC, its CEO and the target company. SRAC’s sponsor was also required to forfeit a portion of its Class B shares. Finally, PIPE investors in that deSPAC transaction were granted recession rights. Although the court’s opinion provides an independent reason for a SPAC’s stakeholders to do the work to ensure all material risks for a business combination are disclosed to investors, the SEC’s statements and actions bolster this as a best practice.

Endnotes

1The court found it unpersuasive both that a portion of the Class B shares would be (i) subject to a lock-up for 18 months following the Business Combination and (ii) subject to forfeiture in the event the stock price failed to trade above $12.50 for 40 trading days in a 60 trading day period within five years of the Business Combination. The court stated that while these terms may have lowered the value of the Class B shares, they would not negate it.(go back)

12 See John Coates, SPACs, IPOs and Liability Risk under the Securities Laws (Apr. 8, 2021), available at https://www.sec.gov/news/public-statement/spacs-ipos-liability-risk-under-securities-laws.(go back)

3See Gary Gensler, Prepared Remarks Before Healthy Markets Association Conference (Dec. 9, 2021), available at https://www.sec.gov/news/speech/gensler-healthy-markets-association-conference-120921.(go back)

4See John R. Ablan and Anna T. Pinedo, The SEC Pursues Action Against SPAC Insiders for Misleading Investors, American Bar Association (Sept. 13, 2021), available at https://businesslawtoday.org/2021/09/the-sec-pursues-action-against-spac-and-insiders-for-misleading-investors/.(go back)

Print

Print