Daniel Taylor is Associate Professor of Accounting at the Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania. This post is based on a recent paper by Professor Taylor; David F. Larcker, James Irvin Miller Professor of Accounting at Stanford Graduate School of Business; Bradford Lynch, PhD Student at The Wharton School; and Brian Tayan, Researcher with the Corporate Governance Research Initiative at Stanford Graduate School of Business.

We recently published a paper on SSRN (“The Spread of COVID-19 Disclosure”) that examines disclosure practices across all U.S. public companies during the initial spread of COVID-19.

Investors rely on corporate disclosure to make informed decisions about the value of companies they invest in. Corporate disclosure includes not only financial statement information that quantifies earnings, cash flows, and changes in the value of assets, but also supplemental information to explain, qualify, or forecast future performance and risks. While the Securities and Exchange Commission requires minimum standards of information in filings, it allows flexibility to go beyond these minimums within the filing and through alternative public channels (such as press releases, earnings conference calls, and industry conferences).

Shareholders value transparency because it improves their ability to price securities, and over time, shareholders’ demand for transparency has led to a steady increase in the amount of information that companies voluntarily disclose beyond regulatory requirements. For a variety of reasons, however, a company might prefer to release less information to the public. A company in a competitive industry or developing a new product might not want to divulge proprietary information that will disadvantage it relative to peers. Alternatively, it might lack foresight about future performance and, out of a desire to avoid legal liability for making inaccurate statements, prefer to disclose less information or use less precision when making statements.

The COVID-19 pandemic presents an interesting scenario whereby an unexpected shock to the economic system led to a rapid deterioration in the economic landscape, causing sharp changes in performance relative to expectations just a few months prior. For most companies, the pandemic has been detrimental. For a few, it brought unexpected demand. In many cases, supply chains have been strained, causing ripple effects that extend well beyond any one company.

How do companies respond to such a situation? What choices do they make, and how much transparency do they offer? How does disclosure vary in a setting where the potential impact is so widely uncertain? The COVID-19 pandemic provides a unique setting to examine disclosure choices in a situation of extreme uncertainty that extends across all companies in the public market. This devastating outlier event provides a rare glimpse into disclosure behavior by managers and boards.

COVID-19 Disclosure

To examine COVID-19 disclosure practices, we reviewed the SEC filings (forms 8-K, 10-Q, and 10-K) of 3,644 publicly listed companies in the United States covering the time period between January 1 and May 29, 2020 for references to COVID-19.

Perhaps ironically, the first company to make specific reference to the coronavirus in a public filing was the biotechnology company Moderna. In contrast to the mostly negative disclosure that would follow in subsequent months, Moderna filed an 8K on January 22 reproducing statements to a news outlet touting its participation “in the potential creation of a vaccine to respond to the current public health threat of the coronavirus”:

Moderna’s mRNA vaccine technology could serve as a rapid and flexible platform that may be useful in responding to newly emerging viral threats, such as the novel coronavirus. While we have not previously tested this rapid response capability, Moderna confirms that we are working with NIH/NIAID/VRC on a potential vaccine response to the current public health emergency. Moderna is committed to addressing infectious diseases and improving global public health.

The first Fortune 100 company to disclose the impact of coronavirus was Starbucks in a 10Q filing January 28. The coffee giant, which derives 14 percent of its sales from China, referenced the potential impact of the virus on its Chinese operations in a subsequent-event notification:

In late January 2020, we closed more than half of our stores in China and continue to monitor and modify the operating hours of all of our stores in the market in response to the outbreak of the coronavirus. This is expected to be temporary. Given the dynamic nature of these circumstances, the duration of business disruption, reduced customer traffic and related financial impact cannot be reasonably estimated at this time but are expected to materially affect our International segment and consolidated results for the second quarter and full year of fiscal 2020.

Starbucks also noted that, “At the time of this filing, the outbreak has been largely concentrated in China, although cases have been confirmed in other countries.”

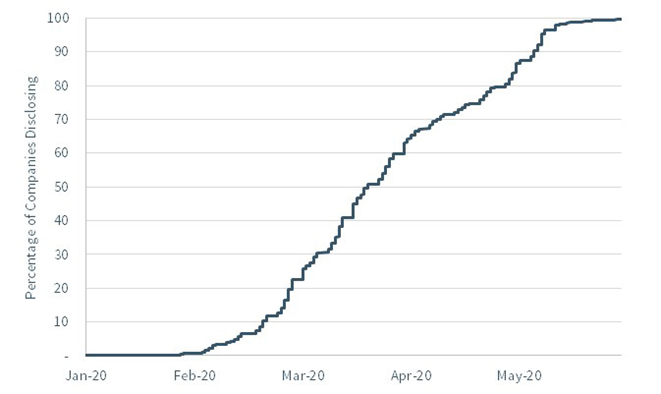

Coronavirus references were relatively scarce in the early months of the year. By January 31, only 0.7 percent of companies had referenced the virus in 10-Ks, 10-Qs or 8-Ks; by February 29, only 22 percent. As the severity of the pandemic became more apparent and shelter-in-place programs instituted across the United States and Europe, disclosure increased exponentially: 41 percent by March 15, 64 percent March 31, 73 percent by April 15, and 86 percent by April 30. By the end of our measurement period, virtually every company (99.6 percent) made some level of disclosure about the pandemic. (One exception is discussed below.) See Exhibit 1.

Exhibit 1: COVID-19 Disclosure

Companies Referencing COVID-19 in SEC Disclosures, Cumulative

Note: Includes Forms 8-K, 10-Q, 10-K.

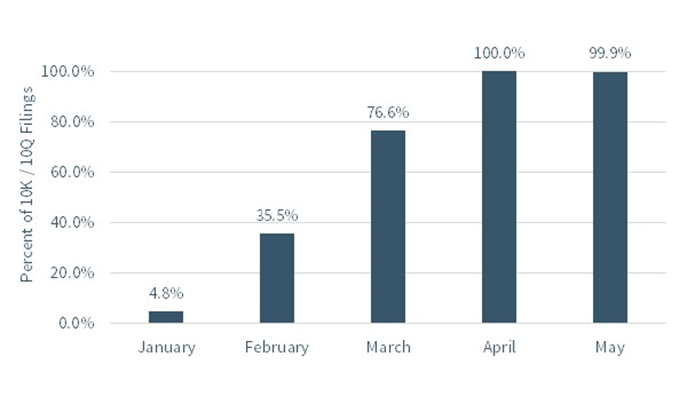

Percent of 10-K and 10-Q Filings Referencing COVID-19

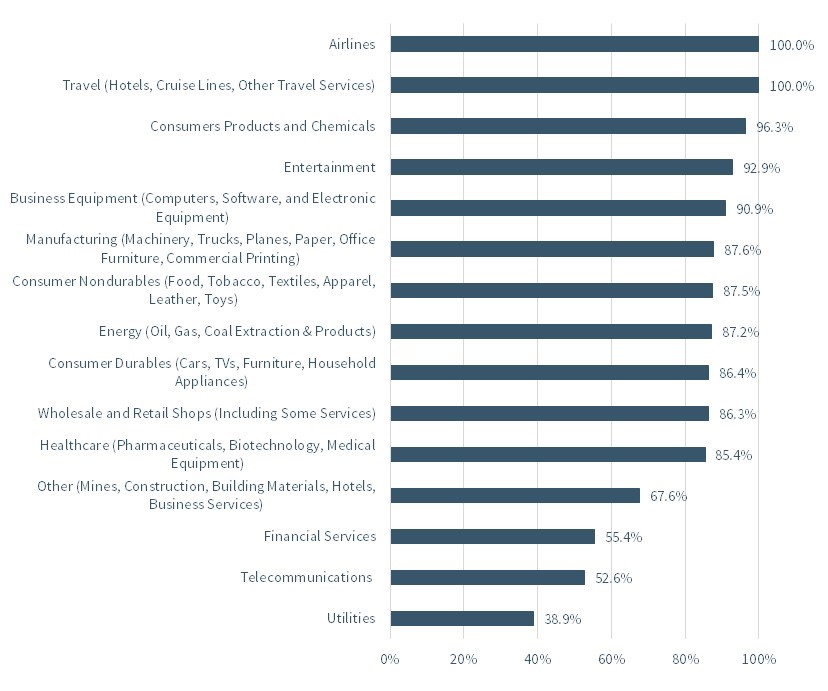

Some noteworthy patterns present themselves when disclosure is examined by industry and over time. Examining cumulative COVID-19 disclosures made by March 31 in 10-Qs and 10-Ks, we see that the prevalence of COVID-19 disclosure varies across industries. Companies in the travel and airlines industry (100 percent) were most likely to have referenced COVID-19. Companies in the entertainment industry also had significantly above-average disclosure rates (91 percent). Perhaps unexpected, the financial services industry, which has incurred significant losses, had relatively low levels of disclosure rates in March (55 percent). The utilities industry had the lowest disclosure rate (39 percent). See Exhibit 2.

Some noteworthy patterns present themselves when disclosure is examined by industry and over time. Examining cumulative COVID-19 disclosures made by March 31 in 10-Qs and 10-Ks, we see that the prevalence of COVID-19 disclosure varies across industries. Companies in the travel and airlines industry (100 percent) were most likely to have referenced COVID-19. Companies in the entertainment industry also had significantly above-average disclosure rates (91 percent). Perhaps unexpected, the financial services industry, which has incurred significant losses, had relatively low levels of disclosure rates in March (55 percent). The utilities industry had the lowest disclosure rate (39 percent). See Exhibit 2.

Exhibit 2: Companies Referencing COVID-19 in SEC Disclosures, by Industry

Notes: Includes Forms 10Q and 10K; industry breakdowns based on Fama-French classifications.

Source: Research by the authors.

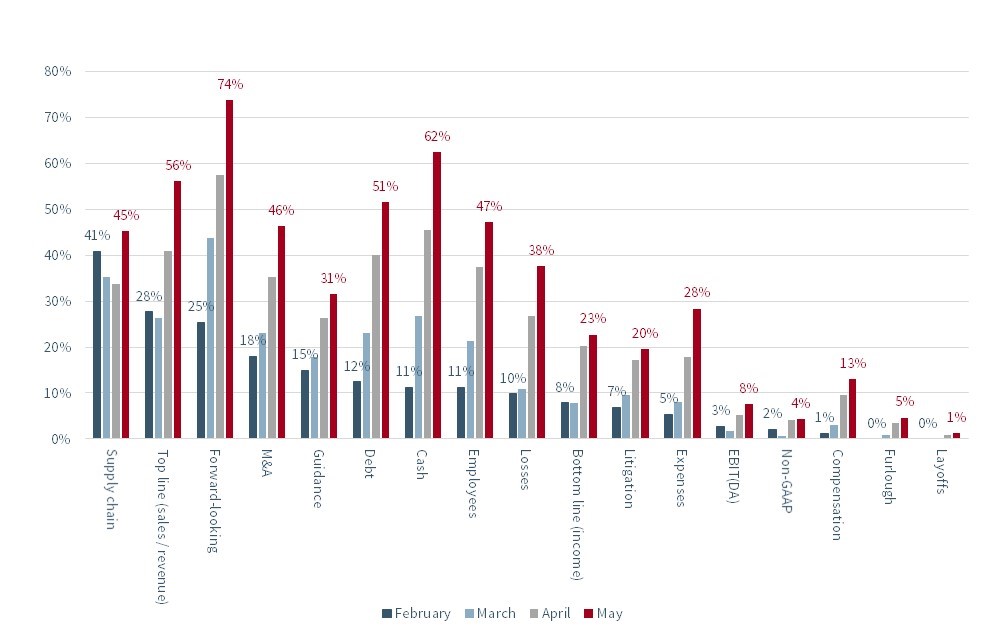

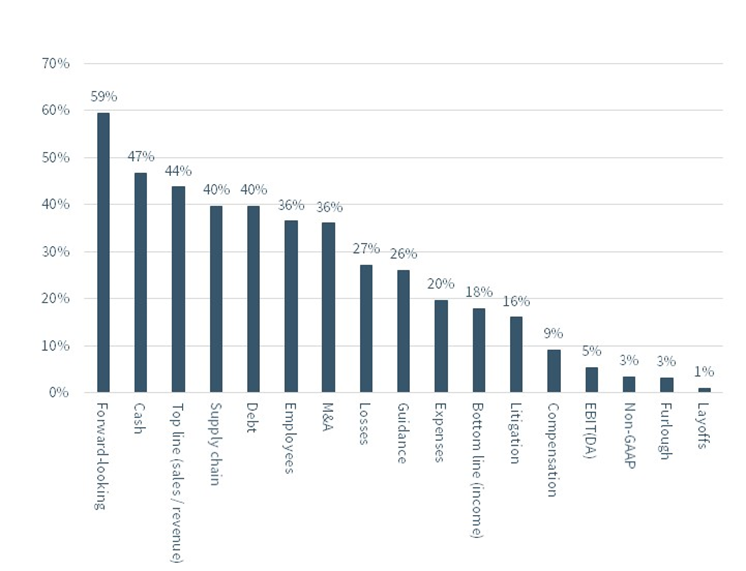

The content of disclosure has also varied over time. Over the entire measurement period (January through May), COVID-19 disclosure most frequently took the form of disclaimers to forward-looking statements (59 percent). For example,

Certain statements may constitute forward-looking statements within the meaning of U.S. federal securities law… and are subject to certain risks and uncertainties that could cause actual results to differ materially… including but not limited to … the outbreak of the recent coronavirus (COVID-19), [etc.].

That is, COVID-19 is disclosed along with a generic laundry list of risk factors. After this, companies next most frequently disclosed the pandemic’s impact on cash (47 percent) and sales (44 percent):

Our key liquidity objective during these unprecedented and uncertain times is to prioritize actions that preserve or improve our cash balance until we are able to resume and sustain normal production and generate revenue.

Revenues were impacted by COVID-19, which led to the suspension of operations, disruptions in our business and closure of our retail stores. We estimate that the impact of COVID-19 on current period revenue was approximately $1.0 billion.

Supply chain (40 percent), such as:

The COVID-19 pandemic has led, and could continue to lead, to interruptions in the delivery of supplies arising from delays or restrictions on shipping or manufacturing, closures of supplier or distributor facilities or other factors.

And debt (40 percent), such as:

While the COVID-19 pandemic caused a disruption in the commercial paper market, we currently still have the ability to borrow funds in this market and expect to continue to be able to do so in the future.

See Exhibit 3.

Exhibit 3: Corporate Disclosure by Topic

Source: Research by the authors.

When the data is analyzed by month, we see that the emphasis of disclosure changed as companies came to different realizations about how the virus would impact their business. In the early months, supply-chain impacts were the most common issue disclosed; by May, disclaimers to forward-looking statements became the most commonly issued disclosure, as companies realized that the full effects of the pandemic could not be easily quantified. Also, we see a significant increase in disclosure on cash positions, as market fears about liquidity and solvency increased. Cash was the seventh most frequently disclosed issue in February; by May, it rose to second (see Exhibit 4). These trends are indicative of a pandemic that was originally seen as contained to China but later one that spread to materially impact the sales, operations, and financial position of most U.S. businesses.

Exhibit 4: Corporate Disclosure by Topic Over Time

Source: Research by the authors.

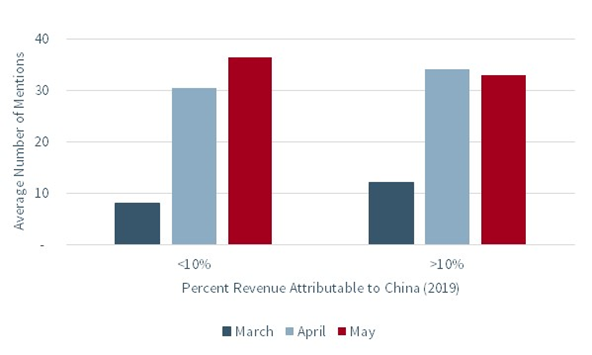

Related to this, disclosure varied based on a company’s exposure to China. Companies that derive more than 10 percent of their revenue from China were sooner to disclose coronavirus impacts. By May, companies with lower exposure to China increased their disclosure volume (see Exhibit 5).

Exhibit 5: Disclosure and Business Exposure to China

Source: Research by the authors.

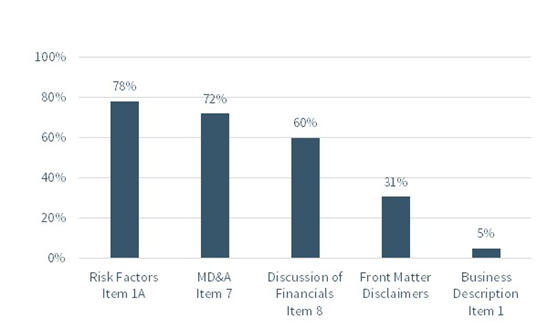

Disclosure is most frequently included in 10-Q and 10-K sections on risk, management discussion and analysis (MD&A), and financials; it is less frequently included in front matter or general business description (see Exhibit 6).

Exhibit 6: COVID-19 Disclosure Within 10K and 10Q Filings

Source: Research by the authors.

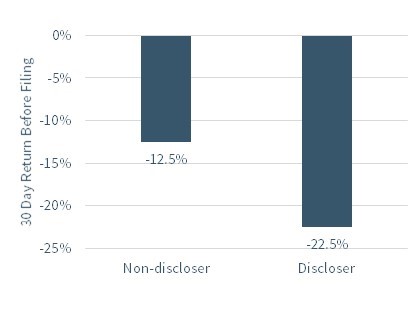

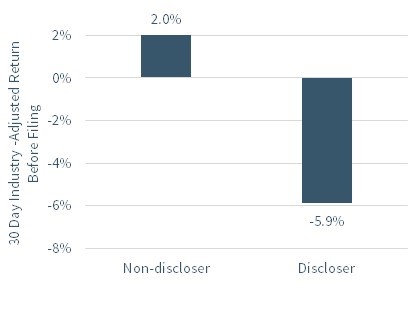

Companies that disclosed COVID-19 impact in March experienced a more negative stock price performance prior to that disclosure. While most companies experienced sharp share price declines in March, companies that issued COVID-19 related disclosure in March experienced 30-day stock price declines that were significantly more negative than companies that did not disclose in March (-22.5 percent versus -12.5 percent). On an industry-adjusted basis, companies that disclosed COVID-19 impact in March experienced a 5.9 percent decline prior to the disclosure while those that made no disclosure in March experienced an industry-adjusted 2.0 percent increase. This data suggests companies that performed worse were more likely to disclose the virus’ impact, potentially because of greater exposure and risks (see Exhibit 7).

Exhibit 7: Returns Leading Up To March 10K and 10Q Disclosures

Source: Research by the authors.

Head-to-Head Competitors

Interesting insights can be gained by comparing the disclosure practices of head-to-head competitors as the pandemic developed.

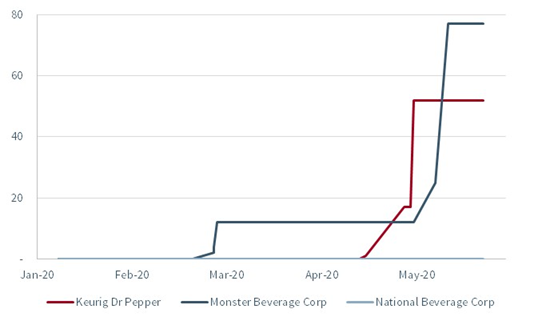

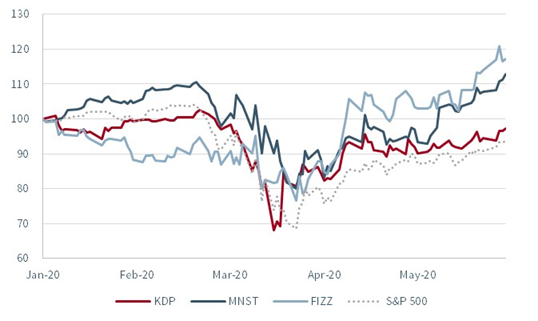

Beverages. Keurig Dr. Pepper, Monster Beverage, and National Beverage (maker of La Croix sparkling water) all have significant exposure to the U.S. beverage market. In late February, Keurig issued both an 8K and a 10K with no references to COVID-19. The very same day, Monster included a cautionary statement in an 8K, warning about “the impact on our global supply chain and our operations due to the recent coronavirus (or COVID-19) outbreak;” the next day Monster included additional disclosure in its 10K. In late April, Keurig included over 50 statements on the virus’ impact on sales, inventory, risk, and employees. By contrast, National Beverage’s SEC filings issued during the January to May period made zero references to COVID-19, nor does their website mention anything related to COVID-19. They are one of only a handful of companies to have remained completely silent about the impact of the virus in filings, despite having significantly negative stock price performance in the month of March (see Exhibit 8).

Exhibit 8: COVID-19 Disclosure: Beverages

COVID-19: Cumulative Disclosure

Stock Price Performance

Source: Research by the authors. Stock price information from Yahoo! Finance.

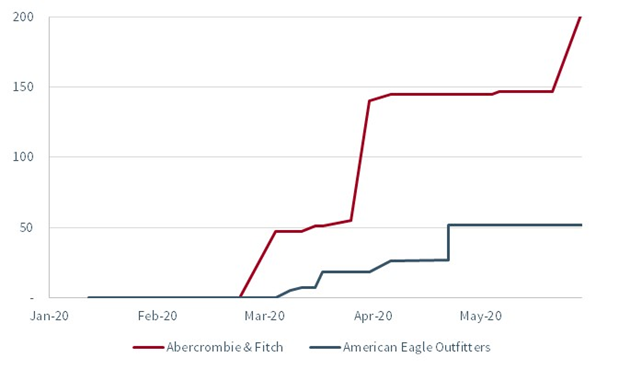

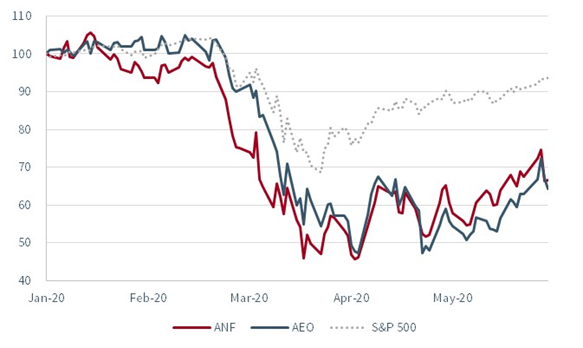

Apparel. American Eagle Outfitters and Abercrombie & Fitch are two specialty apparel companies with similar markets and distribution channels. From an economic perspective, they have both been severely impacted by the pandemic, which resulted in the temporary closure of many of their retail outlets. The companies, however, took different approaches to when and where to disclose the impact of COVID-19 on their businesses. In March, Abercrombie & Fitch made approximately 150 references to the virus in 8K and 10K filings, describing its estimated impact on sales, margins, operations, and regional exposure. During this time, American Eagle Outfitters made less than 20, despite the fact that it also issued a 10K during the month. It was not until the company marketed a convertible bond on April 22 that it provided extensive disclosure about the harm the pandemic inflicted on its business (see Exhibit 9).

Exhibit 9: COVID-19 Disclosure: Apparel

COVID-19: Cumulative Disclosure

Stock Price Performance

Source: Research by the authors. Stock price information from Yahoo! Finance.

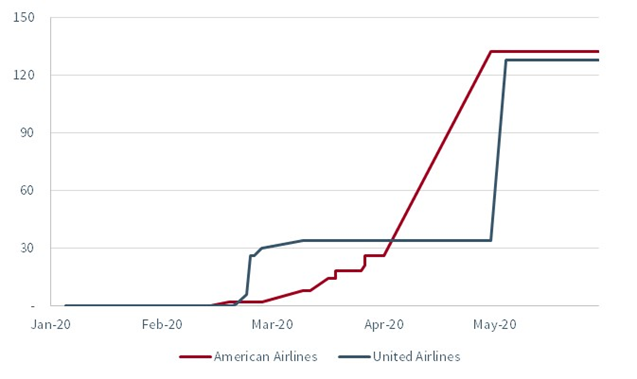

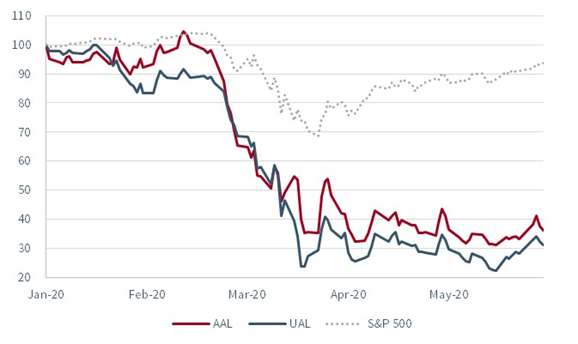

Airlines. American Airlines and United Airlines issued 10Ks six days apart. On February 19, American made two references to the disease, noting that the “coronavirus outbreak that originated in or around Wuhan, China in January 2020 has resulted in the widespread suspension of commercial air service to the region.” It did not elaborate beyond this, despite the fact that American operated flights to and from China. By contrast, United made multiple references to the virus, warning that “as of the date of this report, the company is experiencing an approximately 100 percent decline in near-term demand to China and an approximately 75 percent decline in near-term demand on the rest of the Company’s trans-Pacific routes.” It also warned that the impact of the virus would depend on “the duration and spread of the outbreak and related travel advisories and restrictions and the impact of the COVID-19 on overall demand for air travel” (see Exhibit 10).

Exhibit 10: COVID-19 Disclosure: Airlines

COVID-19: Cumulative Disclosure

Stock Price Performance

Source: Research by the authors. Stock price information from Yahoo! Finance.

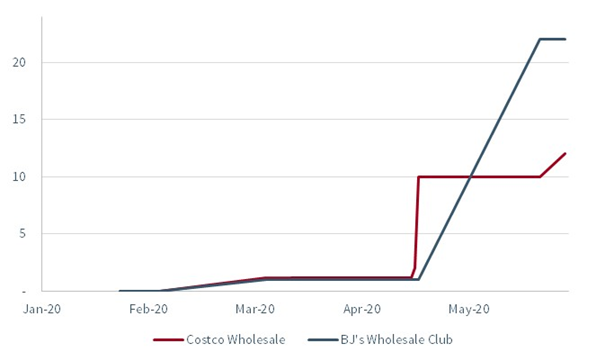

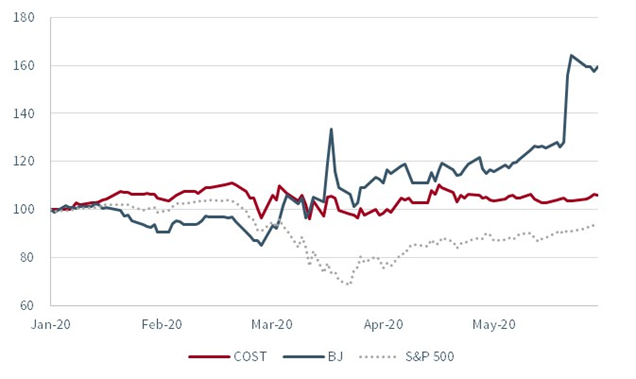

Big Box Retailers. In contrast to the vast majority of U.S. companies, COVID-19 provided an unexpected financial windfall to big box retailers, including Costco and BJ’s Wholesale. Both companies issued 8Ks on March 5: Costco attributed its 10 percent increase in sales in part to elevated demand from the virus; BJ’s simply noted in its cautionary statements that future results could be impacted. In BJ’s March 19 10K, the company made no reference to the virus but did add a new paragraph to its risk factors, noting that results could be impacted by “public health emergencies” or a “pandemic.” When Costco filed a 10Q on March 12, it made no updates to its risk factors: “There have been no material changes in our risk factors from those disclosed in our Annual Report on Form 10-K [filed 10-11-2019 – emphasis added]” (see Exhibit 11).

Exhibit 11: COVID-19 Disclosure: Big Box Retailers

COVID-19: Cumulative Disclosure

Stock Price Performance

Source: Research by the authors. Stock price information from Yahoo! Finance.

Why This Matters

- The COVID-19 pandemic provides a unique opportunity to examine disclosure practices of companies relative to peers in real time about a somewhat unprecedented shock that impacted practically every publicly listed company in the U.S. We see that decisions varied considerably about whether to make disclosure and, if so, what and how much to say about the pandemic’s impact on operations, finances, and future. What motivates some companies to be forthcoming about what they are experiencing, while others remain silent? Does this reflect different degrees of certitude about how the virus would impact their businesses, or differences in managements’ perception of their “obligations” to be transparent with the public? What does this say about a company’s view of its relation and duty to shareholders?

- In one example, we saw a consumer beverage company make zero references to COVID-19 in its SEC filings and website, despite the virus plausibly having at least some impact on its business. In another example, we saw a company claim no material changes to its previously reported risk factors when managers almost certainly had relevant information about the virus and the likely impact on sales and operations. What discussion among the senior managers, board members, external auditor, and general counsel leads to a decision to make no disclosures? What should shareholders glean from this decision, particularly in light of peer disclosure?

- The COVID-19 pandemic represents a so-called “black swan” event that inflicted severe and unexpected damage to wide swaths of the economy. What strategic insights will companies learn from this event? Can boards use these insights to prepare for other possible outlier events, such as climate events, terrorism, cyber-attacks, pandemics, and other emergencies? Should these insights be disclosed to shareholders?

The complete paper is available here.

Print

Print