Gur Aminadav is a Finance & Research Advisor at the London Business School; and Elias Papaioannou is Professor of Economics at the London Business School and the Hal Varian Visiting Professor at MIT Department of Economics. The post is based on their recent article, forthcoming in the Journal of Finance.

Understanding the driving forces and consequences of the various types of corporate control are core inquiries of corporate finance. While most economics and legal theory distinguishes between widely-held corporations with dispersed ownership and controlled firms where a dominant shareholder exerts control, corporate structures are complex. Pyramids that allow shareholders to influence decisions over their cash-flow rights and cross-holdings of equity in business groups are pervasive. Moreover, ownership and control are often hidden behind shell companies incorporated in off-shore centers. Equity blocks—that entail some controlling rights—are commonplace, even in companies that most would coin as widely-held.

In a series of influential works Rafael La Porta, Florencio Lopez-de-Silanes, Andrei Shleifer and Robert Vishny (1997, 1998, 1999) tried to bridge economics and law research, compiling data on ownership concentration, corporate control, and legal protection of investors for a large number of countries. The subsequent voluminous literature on law and finance explores the role of the legal tradition, imposed by colonial powers, as well as corporate law, shareholder and creditor protection, securities legislation, and regulatory features on corporate control and finance (see La Porta, Lopez-de-Silanes, and Sheifer (2006) for an overview).

In a recent article, we explore the role of legal origin on corporate control across the world, relying on a newly-compiled dataset that codifies control for 42,700 listed firms, incorporated in 127 countries in 2007-2012. This is a considerably larger sample than that used by earlier papers or country/regional case-studies. Given the wide use of equity blocks, we distinguish between three types of firms: widely-held corporations, widely-held corporations with one or more equity block(s), defined as voting rights in excess of 5%, and controlled firms with a dominant shareholder. We split controlled firms into state-controlled, family-controlled, and controlled by other listed or private firms. Our analysis proceeds in three steps.

Mapping Corporate Control

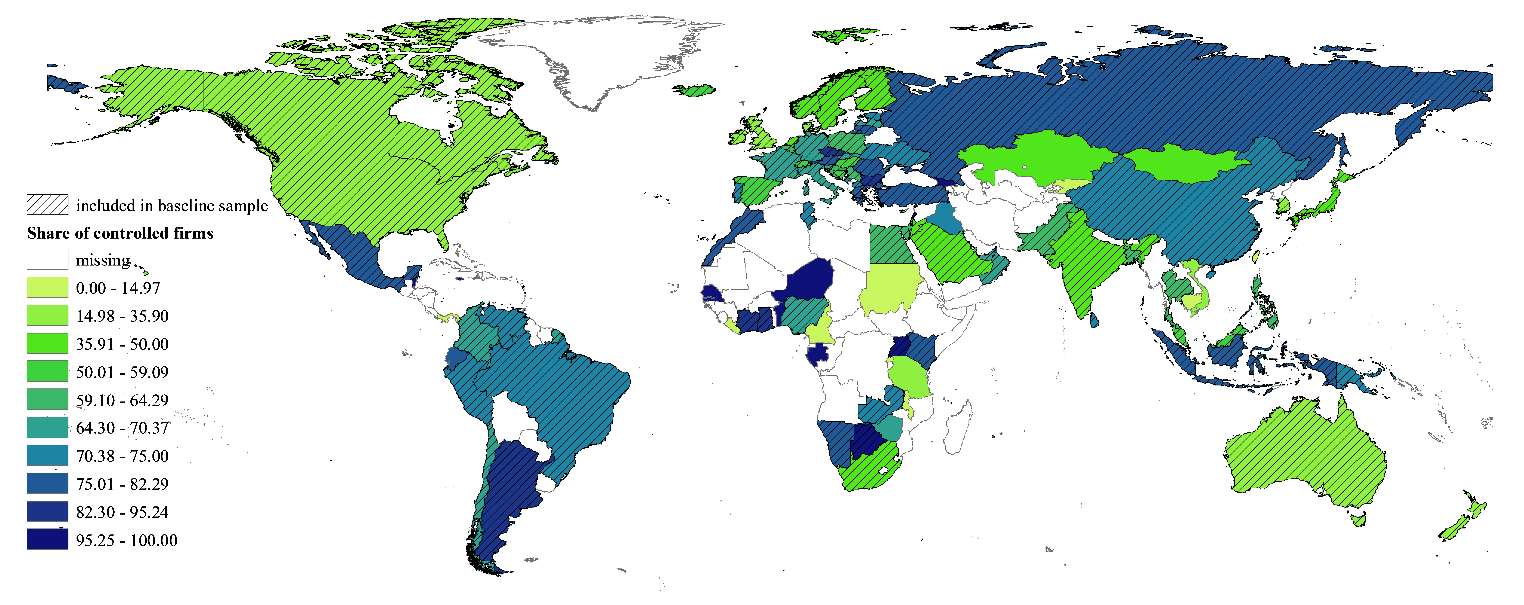

In the first part of our article, we provide an anatomy of corporate control with the newly compiled data that cover roughly 90% of world stock market capitalization in 2012. Figure 1 provides a mapping. The Berle and Means (1932) type of corporation with many small shareholders is almost absent in Africa (in Uganda, Ivory Coast, Ghana, Namibia, Botswana, and Kenya more than 75% of the firms are controlled) and in Eastern Europe (in the Czech Republic, Bulgaria, Lithuania, Romania, and Russia more than 75% of the firms have a controlling shareholder). In contrast, the share of controlled firms is low (below 30%) in New Zealand, Canada, US, UK, Ireland, Australia, and Taiwan. There is non-negligible variability within regions. In Western Europe, the share of controlled firms ranges from around 80% in Austria, Malta, and Greece to around 20% in the United Kingdom and Ireland with Spain and Switzerland in the middle. In Asia, corporate control ranges from 78% in Indonesia to around 20%-30% in Australia and Taiwan and around 47% in India.

Figure 1. Corporate Control across the World

We also provide mappings for the pervasiveness of family-controlled firms. The cross-country mean (median) is 17.5% (16.7%). When we add firms controlled by unidentified private owners, the cross-country average (median) doubles. Family-control is omnipresent in countries with strong family ties, such as Greece, Italy, Portugal, Argentina, and Lebanon, while there are relatively few family-controlled listed corporations in Taiwan, Ireland, and Australia. Likewise we map state control around the world. Government control is (close to) zero in 18 countries (e.g., United States, Canada, Latvia, Estonia), but it exceeds 20% in 11 countries, mostly in Africa (e.g., Uganda, Ghana), the Arab World (Oman, Qatar, UAE), and also Russia and China.

Legal Tradition and Corporate Control

In the second part of the article, we re-examine the “reduced-form” correlation between corporate control (and ownership concentration) and legal origin, as well as economic development. The large sample is useful, as most previous studies worked in smaller firm samples with limited country coverage; and they often focused on large firms. The big sample is especially helpful in examining heterogeneity with respect to firm size and age, aspects that may affect control and in turn be affected by the institutional environment. We uncover the following robust regularities.

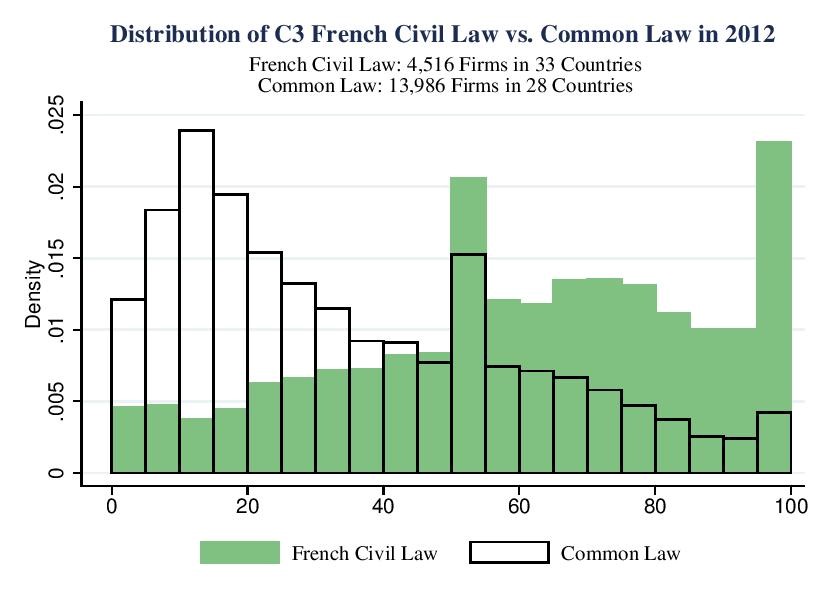

1. There are large differences in corporate control across legal families. The share of controlled firms is the highest among French civil-law countries, followed by German and then Scandinavian civil-law countries. The share of controlled firms is the lowest in common-law countries. Similar patterns apply for ownership concentration, measured as the sum of the voting rights of the three (or five largest) shareholders (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Ownership Concentration in French Civil Law and Common Law Countries

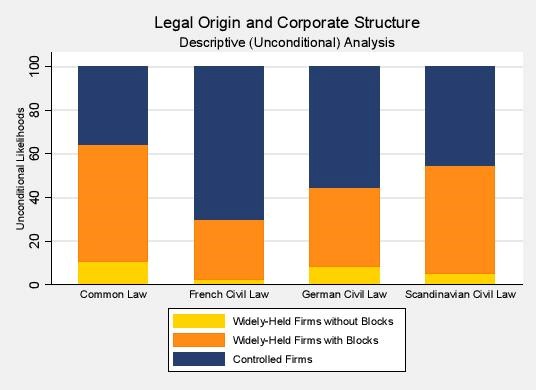

2. Equity blocks are commonplace, as we observe them in more than 80% of non-controlled firms; this applies across all regions, in both civil-law and common-law countries. Yet, the share of widely-held firms with blocks is the highest in French civil-law and the lowest in common-law countries (figure 3).

Figure 3. Corporate Control across Legal Families

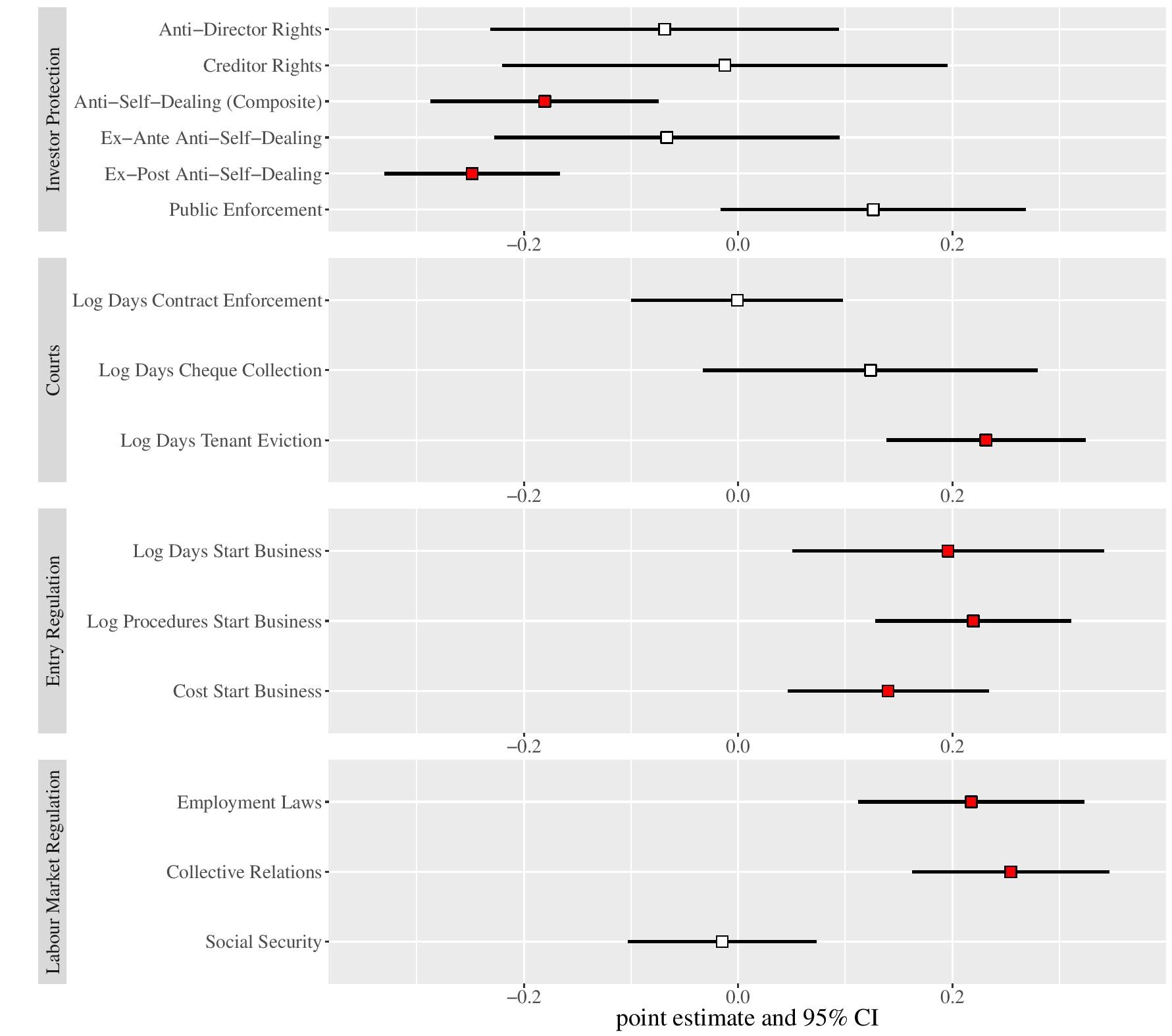

3. Institutions and Corporate Control. In the third part of the article, we examine the correlation between corporate control and the institutional features that legal origin theories emphasize. While these correlations do not identify causal effects, they allow examining the potential role of investor protection, court efficiency, red tape, and labor market regulation on corporate control in a simple unified framework. Figure 4 gives a summary of the correlational analysis. The graph plots the univariate correlation between corporate control and institutional proxies of investor protection, courts quality, entry, and labor market regulation. The dots show the point estimate (bold red dots denoting statistically significant correlation) and the horizontal lines show 95% confidence intervals (based on clustered at the country standard errors).The significant cross-country correlation between corporate control (and ownership concentration) and legal origin applies for large, medium, and small listed firms; it also applies for young and old firms.

4. Dispersed ownership correlates with GDP per capita. But, the correlation is not particularly strong, as it masks heterogeneity. The negative correlation between income and control is significant only in the sample of above-median-size firms; it is especially strong for big corporations (top 10% of global market cap). The correlation is zero in the sample of small and medium-sized public companies. This novel finding echoes the results of Hsieh and Klenow (2014), who after showing that productivity differences between Mexico, India, and the United States (US) are pronounced for (very) large firms and muted for small firms, hypothesize that this reflects medium-sized firms’ inability to expand in emerging markets, because of financial frictions.

Institutions and Corporate Control

In the third part of the article, we examine the correlation between corporate control and the institutional features that legal origin theories emphasize. While these correlations do not identify causal effects, they allow examining the potential role of investor protection, court efficiency, red tape, and labor market regulation on corporate control in a simple unified framework. Figure 4 gives a summary of the correlational analysis. The graph plots the univariate correlation between corporate control and institutional proxies of investor protection, courts quality, entry, and labor market regulation. The dots show the point estimate (bold red dots denoting statistically significant correlation) and the horizontal lines show 95% confidence intervals (based on clustered at the country standard errors).

The key takeaways are:

- Corporate law provisions allowing legal action against managers who abuse their position, are systematically linked to disperse ownership. This result is consistent with the core idea of the law and finance literature that corporate control substitutes for weak shareholder protection (La Porta et al., 1997, 1999).

- The correlation between control and creditor rights is small and statistically insignificant. This result reaffirms the finding of La Porta et al. (1999) that shareholders’ rather than creditors’ rights matter for corporate control.

- Legal formalism, as reflected by various measures of the time needed to resolve disputes via courts, is weakly related to corporate control and ownership concentration.

- Corporate control and ownership concentration are not much related to entry barriers and red tape.

- There is a strong correlation between control and labor regulation. In countries with a high percentage of controlled firms, labor legislation is sclerotic, imposing restrictions for overtime and firings; and union membership and power are relatively high. This result is consistent with political theories of corporate control that emphasize the role of post-Great Depression and World War II welfare-state policies in finance (Roe, 2000, 2006; Rajan and Zingales, 2003, 2004). These theories stress the interplay between controlling shareholders (families and the state), workers, and outside investors that labor laws shape (Pagano and Volpin, 2005). Controlling shareholders and corporate insiders collaborate with employers at the expense of minority-outside shareholders in countries with stringent labor legislation.

Figure 4. Corporate Control and Institutions. Univariate Correlations. 2004-2012

Our large sample findings, therefore, support both legal origin (e.g., Glaeser and Shleifer, 2002; La Porta et al. 1998) and political theories of corporate control (Roe, 2000; Rajan and Zingales, 2003, Pagano and Volpin, 2005). In line with the law and finance literature, corporate control is systematically linked to the legal origin and the protection of minority shareholders. In line with political theories, economic development is also a strong correlate of control, though only for the (very) large firms that tend to be the most productive. Labor market (welfare state) legislation is also a strong correlate of corporate control, suggesting inter-linkages between finance and labor markets that most likely reflect the political equilibrium.

The complete article is available article.

Print

Print