Joseph Bachelder is special counsel at McCarter & English LLP. This post is based on an article by Mr. Bachelder published in the New York Law Journal. Andy Tsang, a senior financial analyst with the firm, assisted in the preparation of this post. Related research from the Program on Corporate Governance includes the book Pay without Performance: The Unfulfilled Promise of Executive Compensation, by Lucian Bebchuk and Jesse Fried and Paying for Long-Term Performance by Lucian Bebchuk and Jesse Fried (discussed on the Forum here).

On Jan. 21, 2018, Tesla granted to its co-founder and chief executive officer, Elon Musk, a performance-based stock option to acquire shares equal to 12 percent of Tesla shares outstanding at the time of grant. This option was discussed in two columns published by the author in the New York Law Journal (May 1 and June 22, 2018), and discussed on the Forum here and here.

On Feb. 26, 2018 another public company, Axon Enterprise, granted a similar option to its co-founder and chief executive officer, Patrick Smith. Like the Tesla/Musk option, it covers shares equal to 12 percent of the employer’s shares outstanding at the time of grant.

These two very large options, with very challenging performance targets, will be referred to in the following discussion as “super options.” Both options were approved by shareholders subsequent to their grants. At the time of writing today’s column, the author was not aware of any other “super options” granted by public companies, except for the option granted by Tesla in 2012 as noted in the following paragraph.

(Tesla granted Mr. Musk two very large options prior to the 2018 option grant. These were discussed in the June 22, 2018 column referred to above. One of the options was granted in 2009 before Tesla became public and covered 8 percent of Tesla shares then outstanding. Part of the grant was subject to attainment of performance targets, part of it vested over time without regard to attainment of performance targets and the remainder vested on grant. The other option, granted in 2012, covered 5 percent of Tesla shares then outstanding and the option grant, like the 2018 option grant, was fully subject to very challenging performance targets. The author is not aware of any prior option grants by Axon to Mr. Smith that had characteristics of “super options.”)

Tesla manufactures electric cars as well as energy generation and storage systems and is headquartered in Palo Alto, Calif. Its revenue for 2017 was $11.8 billion. Its market cap as of Dec. 15, 2018 was $62.8 billion.

Axon’s business includes the manufacture of electrical weapons and wearable cameras (such as those used by police forces). It is headquartered in Scottsdale, Ariz. Its revenue for 2017 was $344 million. Its market cap as of Dec. 15, 2018 was $2.6 billion.

“Super Option” Performance Targets

Each “super option” is comprised of 12 equal “tranches,” each tranche representing 1 percent of the company’s shares at the time of grant. (A discussion of performance targets, limited to the Tesla/Musk option, is contained in the May 1, 2018 column referred to above.)

A tranche vests only upon (x) the achievement by the company’s stock of the market cap level assigned to that tranche and (y) the achievement by the company of either one of the two operational targets as discussed below.

(a) Achievement of Market Cap Targets. Each of the 12 tranches is assigned a market cap target. In the case of Tesla, the market cap targets range from $100 billion to $650 billion, in $50 billion increments. In the case of Axon, the market cap targets range from $2.5 billion to $13.5 billion, in $1 billion increments. A market cap target is achieved on the date when the average market caps for both the six-month period and the 30-day period ending on that date (or ending on the day preceding that date in the case of Axon) exceed the applicable target for the tranche. Once reached, the market cap target is considered achieved even if the market cap subsequently drops below that target level. The market cap targets are subject to adjustments to take into account transactions, including acquisitions, divestitures and spin- offs, that are considered material to the achievement of the targets.

(b) Achievement of Operational Targets. There are two sets of operational targets: revenue targets and EBITDA targets. (EBITDA is adjusted by removing any charge for stock-based compensation.)

(i) Revenue: The revenue targets are set in 8 increments. In the case of Tesla, they range from $20 billion to $175 billion. In the case of Axon, they range from $0.7 billion to $2 billion. A revenue target is achieved when revenue equals or exceeds that target for four consecutive quarters.

(ii) Adjusted EBITDA: The EBITDA targets also are set in 8 increments. In the case of Tesla, they range from $1.5 billion to $14 billion. In the case of Axon, they range from $125 million to $230 million. An EBITDA target is achieved when EBITDA, adjusted as described above, equals or exceeds that target for four consecutive fiscal quarters.

Like the market cap targets, the operational targets are subject to adjustments to take into account transactions, including acquisitions, divestitures and spin-offs, that are considered material to the achievement of the targets.

(c) Matching Achieved Market Cap Targets With Achieved Operational Targets. When a market cap target for an option tranche, as described above, is achieved it can be matched with either an achieved revenue target or an achieved EBITDA target, as described above. When that “match” occurs the tranche (representing 1/12 of the option) vests.

Following are three characteristics of the operational targets that should be noted:

- The two types of operational targets are not linked (they are simply two sets of targets) and an achieved target in either category can be “matched” with an achieved market cap target.

- An achieved revenue target or an achieved EBITDA target, until used as a “match” for vesting purposes, continues to be available for matching even if revenues or adjusted EBITDA, as the case may be, subsequently fall below the achieved target level.

- Once an achieved revenue target or an achieved EBITDA target is matched with an achieved market cap resulting in vesting it cannot be used again.

“Super Option” Values

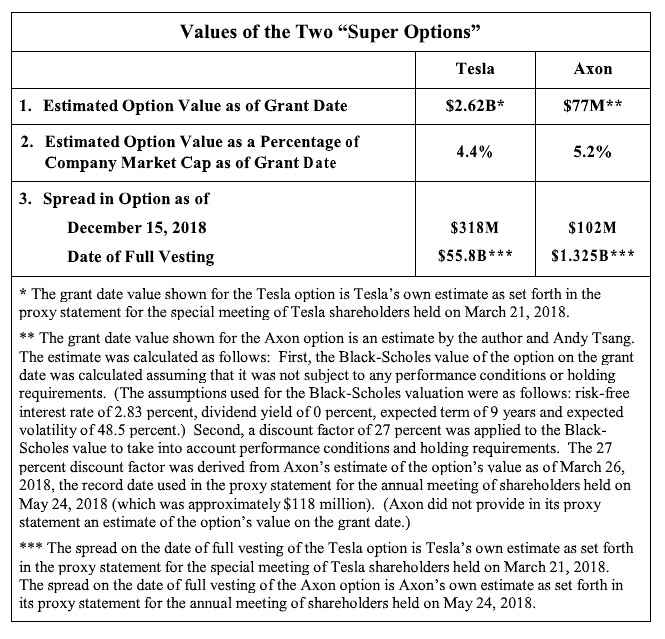

The following chart shows values associated with the Tesla/Musk option and the Axon/Smith option.

Impact on Company Market Cap of Achieving Performance Targets

The following chart shows the impact on each company’s market cap if threshold-vesting performance targets (single tranche vests) and maximum-vesting performance targets (all 12 tranches vest), respectively, are achieved.

Future of “Super Options”

Points in Support of “Super Options”:

(1) If a company is trying to attract a new CEO, a “super option” represents a very compelling reason for the CEO candidate to accept the job offer.

(2) For a company with high growth potential, a “super option” provides an extraordinary incentive to the CEO to maximize growth in operating performance and total stock market value of the company.

Points Against “Super Options”:

(1) 12 percent of outstanding shares of a company is an extraordinary portion of such shares to commit to an option grant to a single individual.

(2) A “super option” may encourage a CEO to take risks that the CEO might not otherwise take, especially if the CEO has no significant ownership in the company.

(3) The two “super options” discussed in this column were granted to CEOs who would be receiving no salary (other than a salary consistent with minimum wage requirements under applicable law) and no annual bonus opportunity after receiving the “super option” grant. Many CEOs and CEO candidates are unlikely to be willing to give up salary and annual bonus opportunity for a “super option” grant.

(4) Elimination of the annual bonus opportunity would eliminate an important yearly process for measuring corporate and individual performance.

(5) The targets for the two “super options” discussed in this column were set for a 10-year period. What happens if the targets are unrealistically high or unrealistically low? If, for example, there was a substantial decline in revenue and EBITDA for a period of one year or several years, it would be very discouraging for a CEO who failed to achieve targets and had no vesting over an extended period of time. This certainly would be the case if the CEO had relinquished salary and annual bonus opportunity in consideration for the award.

Conclusion

“Super options” represent a new and unique form of long-term incentive. In each of the two cases discussed in today’s column, the grant was made to a co- founder CEO. Based on the proxy statement discussing the Tesla/Musk option, Mr. Musk had a 21.9 percent equity ownership in Tesla as of Dec. 31, 2017. That 21.9 percent equity ownership had a value of approximately $13.8 billion as of Dec. 15, Based on the proxy statement discussing the Axon/Smith option, Mr. Smith had a 2.3 percent equity ownership in Axon as of Feb. 23, 2019. That 2.3 percent ownership had a value of approximately $60 million as of Dec. 15, 2018. Can CEOs with less wealth afford the high-reward-but-high-risk type of a long-term incentive represented by the “super option”—especially if they have to relinquish all, or substantially all, of their salary and bonus opportunity as consideration for being granted the “super option”?

Print

Print