Frank M. Placenti is partner at Squire Patton Boggs (US) LLC. This post is based on a recent paper by Mr. Placenti that was commissioned by the American Council for Capital Formation.

Proxy advisory firms have been a feature of the corporate landscape for over 30 years. Throughout that time, their influence has increased, as has the controversy surrounding their role.

In Blackrock’s July 2018 report on the Investment Stewardship Ecosystem, [1] the country’s largest asset manager noted that, while it expends significant resources [2] evaluating both management and shareholder proposals, many other investor managers instead rely “heavily” on the recommendations of proxy advisors to determine their votes, and that proxy advisors can have “significant influence over the outcome of both management and shareholder proposals.”

That “significant influence” has been a source of discomfort for many public company boards and executives, as well as organizations like the American Council for Capital Formation, the Society for Corporate Governance and the Business Roundtable. They have charged that proxy advisors employ a “one-size-fits all” approach to governance that ignores the realities of differing businesses. Some have also complained that the advisors’ reports are often factually or analytically flawed, and that their voting recommendations increasingly support a political and social agenda disconnected from shareholder value.

Academics have written that there is no empirical evidence that proxy advisors’ benchmark governance policies promote shareholder value, effective governance or any meaningful advancement of the advisors’ championed social causes. Indeed, a 2009 study by three Stanford economists concluded that, when Boards altered course to implement the compensation policies preferred by proxy advisors, shareholder value was measurably damaged. [3] A second Stanford study reported that those charged with making investment decisions within an investment manager were involved in voting decisions only 10% of the time, suggesting a troubling de-coupling of voting decisions from any investment selection or the company performance that motivates that selection. [4]

While proxy advisors have had a raft of detractors, some institutional investor groups have defended the proxy advisors’ role, asserting that the outsourcing service they provide is indispensable if institutional investors are to fulfill their perceived regulatory responsibility to vote on every issue presented for shareholder action at the hundreds of companies in which they hold positions.

For their part, proxy advisors contend that complaints about the quality of their analysis are overblown, that they make few material errors, and that disputes with companies most often represent mere “differences of opinion,” as recently claimed in a May 30, 2018 letter from Institutional Shareholder Services (ISS) to six members of the Senate Banking, Housing, and Urban Affairs Committee. [5]

As in many such debates, where you stand depends on where you sit, and the absence of data has hindered an informed discussion.

Concerns About Over-Reliance on Proxy Advisors

Among the principal laments about proxy advisors has been that many institutional investors essentially delegate their voting decisions to these advisors. Investors generally deny any such delegation and argue that while they are guided by the advisors’ recommendations, they make their own voting decisions. ISS has made similar assertions. [6]

ISS and Glass Lewis have contended that the close correlation between their recommendations and their clients’ voting records should not be of concern because most clients have their own “custom” voting guidelines that are the basis for their voting recommendations. [7] However, practitioners who have examined those “custom” guidelines have often remarked that that many contain only minor deviations from the advisors’ benchmark standards that give rise to the “one-size-fits-all” criticism.

In the midst of this debate, newly-published empirical evidence makes clear that, while the recommendations of ISS are not followed by their clients 100% of the time, they are followed nearly 100% of the time by many of the largest fund managers in the country.

An independent review of reported Proxy Insight data for the published by the American Council for Capital Formation (ACCF) in October 2018 examined the historical voting records of 175 asset managers with more than $5.0 trillion in assets under management. Links to the ACCF reports are available here and here. The statistics reported by ACCF can fairly be viewed as evidence that, despite their protests to the contrary, for all practical purposes, some funds have delegated the exercise of their fiduciary voting obligations to their proxy advisors.

The ACCF analysis reveals that:

- 175 asset managers managing over $5.0 trillion in assets have historically voted consistently with ISS recommendations 95% of the time, whether the matter at issue was a management proposal or a shareholder proposal, and

- 82 of the asset managers with over $1.3 trillion of assets under management voted consistently with ISS’ recommendations 99% of the time, whether the matter in question was a management proposal or a shareholder proposal.

The ACCF data was designed to evaluate whether the advisor’s voting percentages were consistent whether the matter under consideration was a management proposal or a shareholder proposal. The consistency of the results for those two categories, regardless of the routine or contested nature of the issue, suggests that these firms are effectively outsourcing their ultimate voting decisions.

Moreover, the ACCF data does not seem to be reflect that large institutions are doing it “right” while smaller funds are forced to resort to reliance on third party advice due to economic necessity. Large and small firms are equally represented in the ACCF findings. The asset managers in the 99% category include some large, well-known and very successful asset managers, as reflected in the list below:

| Asset Manager | Mgmt. Proposals | Sh. Proposals |

|---|---|---|

| Blackstone | 100.0% | 100.0% |

| AQR Capital Management LLC | 99.9% | 99.6% |

| United Services Automobile Association | 99.9% | 99.5% |

| Arrowstreet Capital | 100.0% | 99.9% |

| Virginia Retirement System | 99.9% | 99.8% |

| Los Angeles County Employees Retirement Association | 99.7% | 99.5% |

| Baring Asset Management | 99.9% | 99.6% |

| Numeric Investors, LLC | 100.0% | 100.0% |

| PanAgora Asset Management, Inc. | 99.8% | 99.5% |

| First Trust Portfolios Canada | 99.9% | 99.3% |

| ProShares | 100.0% | 99.6% |

| Kentucky Teachers’ Retirement System | 99.7% | 99.6% |

| Stone Ridge Asset Management | 100.0% | 99.8% |

| Pensionskasse SBB | 99.7% | 99.5% |

| Euclid Advisors LLC | 99.6% | 99.9 |

| Rafferty Asset Management, LLC | 100.0% | 100.0% |

| Driehaus Capital Management LLC | 99.9% | 99.7% |

| Alameda County Employees’ Retirement Association | 99.9% | 99.6% |

| DSM Capital Partners LLC | 99.6% | 100.0% |

| Weiss Multi-Strategy Advisers LLC | 99.9% | 99.80% |

*All voting and Assets Under Management data reported by ACCF was derived from Proxy Insight reports dated October 13, 2018 and was filtered to include only those funds that had voted on more than 100 resolutions. ACCF derived assets under management data, noted with an asterisk, from IPREO data for that same period due to the unavailability of that data from Proxy Insights. ISS alignment data on the platform reflects all data available for each investor, which generally dates back as early as July 1, 2012 through the date it was pulled.

While it is clear many substantial investment funds rely on ISS for virtually all of their voting decisions, that is not true for all institutional investors. Several of the nation’s largest funds like Vanguard, State Street, Blackrock and others have chosen to implement their own internal proxy voting analysis and have increased the size of their internal corporate governance teams. The Financial Times has reported:

“New York-based BlackRock now has the largest corporate governance team of any global asset manager, after hiring 11 analysts for its stewardship division over the past three years, bringing total headcount to 31. Vanguard, the Pennsylvania-based fund company that has grown quickly on the back of its low-cost mantra, has nearly doubled the size of its corporate governance team over the same period to 20 employees. State Street, the US bank, has almost tripled the size of the governance team in its asset management division to 11. Both Vanguard and State Street said their governance teams will continue to grow this year.” [8]

These efforts are to be applauded as they reflect a commitment of significant resources to making informed and independent voting decisions. Moreover, in the experience of most practitioners, those funds that employ their own internal resources tend to show a greater willingness to engage in dialogue with companies who feel the need to express disagreement with their initial voting decisions.

Concerns About Electronic Default Voting and Its Impact

For years, companies have anecdotally reported an almost immediate spike in voting after an advisor’s recommendation is issued, with the vote demonstrating near lock-step adherence to the recommendation.

A few companies have been bold enough to contend that the immediacy of the vote reveals that institutional investors are not taking time to digest the information in the advisors’ often-lengthy reports, only to experience the sting of investor backlash.

Moreover, it is now known that many of these votes are cast through electronic ballots with default mechanisms. These default settings must be manually overridden for the investor to vote differently than the advisor recommends. [9] This immediate default voting allows no time for companies to digest the advisor’s report and effectively communicate to their investors any objections they may have to it. The combination of default electronic voting and the speed with which votes are cast has been dubbed “robo-voting.”

Public companies who do not receive the advisors’ reports in advance are caught flat-footed by an adverse recommendation and are left to scramble to file supplemental proxy materials and otherwise struggle to communicate their message to investors. When those investors have already cast their vote by default electronic ballot, getting them to engage in a discussion of the issues, let alone reverse their vote, has proven to be practically impossible in most cases. [10]

Is Robo-Voting Real?

Although many public companies and even proxy solicitation firms have anecdotally reported the existence of an immediate spike in voting in the wake of ISS and Glass Lewis recommendations, the size and prevalence of that spike have not been empirically examined in published reports.

In an effort to generate relevant data, four major U.S. law firms including Squire Patton Boggs recently collaborated on a survey of public companies seeking information about the existence, size and nature of the voting spike in the wake of an adverse proxy advisor recommendation. An adverse recommendation was defined as one urging a vote against a management proposal or in favor of a shareholder proposal opposed by the company’s board of directors.

One hundred companies were asked about their experiences in the 2017 and 2016 proxy seasons. In particular, they were asked to report on the number of adverse recommendations they had received from proxy advisors in those years.

Thirty-five companies in 11 different industries reported an adverse proxy advisor recommendation during that period, totaling 93 separate instances. Responses ranged from one to 11 adverse recommendations in a single year. A summary of the survey is available here.

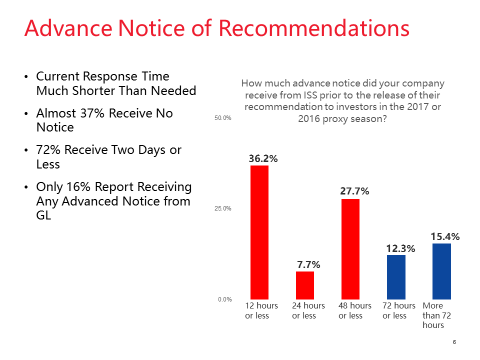

More specifically, companies were asked to quantify the amount of advance notice they received from the relevant proxy advisor regarding adverse recommendations. Almost 37% of companies reported that ISS did not provide them the opportunity to respond at all. Companies indicated that Glass Lewis was even worse—with 84% of respondents indicating they did not receive any notice from the advisor before an adverse recommendation.

When a company did receive notice, it was often not enough time to generate a response. Nearly 85% of companies that were given notice from ISS indicated they received less than 72 hours to respond to the adverse recommendation, with roughly 36% of these companies indicating they received less than 12 hours-notice from ISS.

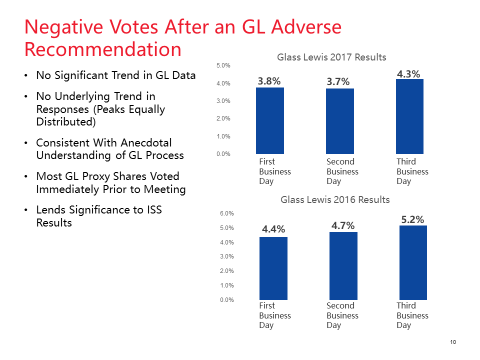

Companies were also asked to report the increase in shares voted within one, two and three business days of the publication of the advisors’ adverse recommendation. Results varied depending on a variety of factors, including whether the recommendation in question was issued by ISS (which broadly employs electronic default voting) or Glass Lewis, (which seems to delay voting until much closer to the time of the annual meeting.)

For the 2017 proxy season, the participating companies reported an average of 19.3% of the total vote is voted consistent with the adverse recommendations within three business days of an adverse ISS recommendation. For the 2016 proxy season, the companies reported an average 15.3% of the total vote being consistent with the adverse recommendations during the same three-day period.

Comparing the data for the voting spike for ISS and Glass Lewis recommendations provided an interesting contrast. Unlike ISS, Glass Lewis does not make extensive use of default electronic voting [11] and reports that it often delays casting votes until much closer to the annual meeting at the instruction of its clients. [12] While the average 3-day spike for ISS was 17.7% for the 2017 proxy season, for Glass Lewis the comparable number was 11.8%.

Companies were also asked to state the time period they believed they would require to effectively communicate with shareholders to respond to an adverse recommendation. One hundred percent of companies stated they would need at least three business days while 68% stated they would need at least five business days to do so. This number must be viewed in the context that nearly 85% of respondents indicated that they received less than 3 days-notice of an adverse recommendation.

While the relatively small data set (and the non-random survey methodology) do not allow statistically significant conclusions to be drawn, the survey does provide empirical data to support the following conclusions:

- There is a discernible voting spike in the near aftermath of an adverse advisory recommendation that is consistent with the recommendation.

- The percentage of shares voted in the first three days represent a significant portion of the typical quorum for public company annual meetings.

- Companies need more time than they are being given to respond to adverse recommendations.

Is This Lack of Response Time Really a Problem?

Should we care that so many shares are being voted before companies can effectively communicate their disagreements with a proxy advisors’ recommendations?

There are two immediate answers to that question.

First, as noted in the July 2018 Blackrock report, many institutional investors rely “heavily” on those recommendations. Indeed, the ACCF report shows that, for at least 175 funds, “heavily” actually means “almost always.”

These institutional investors have fiduciary duties to their beneficiaries or retail investors to have all relevant information, including a company’s response to a proxy advisor’s recommendation, before voting. While a company’s original proxy statement performs a portion of that function, it cannot respond (in advance) to errors or flaws in a proxy advisor’s recommendation.

That leads to the second reason we should care about the lack of time to respond. Proxy advisor recommendations are not always right.

How Prevalent are Errors in Proxy Advisor Reports?

As far back as 2010, the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) highlighted concerns that “proxy advisory firms may…fail to conduct adequate research and base [their] recommendations on erroneous or incomplete facts.” [13]

In the years since that observation, public companies have continued to complain about errors in proxy advisor recommendations and have sometimes voiced those concerns in supplemental proxy filings with the SEC.

A review of supplemental proxy filings during 2016, 2017 and a partial 2018 proxy seasons (through September 30, 2018) provides some insight on the nature of this problem.

In conducting that review, we established four categories of filings in which companies challenged a proxy advisor’s recommendation:

- No Serious Defects. Filings specifying no serious defect in the report, but simply expressing a disagreement. Often, these filings sought to justify poor company performance by reference to external market or economic forces. (These filings were not further tabulated.)

- Factual Errors. Filings claiming that the advisor’s reports contained identified factual errors.

- Analytical Errors. Filings claiming that the advisor’s reports contained identified analytical errors, such as the use of incongruent compensation peer group data or the use of peer groups that inexplicably varied from year to year.

- Serious Disputes. Filings that identified specific problems with the advisors’ reports often stemming from the “one-size-fits-all” application of the proxy advisors’ general policies. These included support for shareholder proposals seeking to implement bylaw changes that would be illegal under the issuer’s state law of incorporation, inconsistent recommendations with respect to the same compensation plan in multiple years, and other serious disputes.

We contend that supplemental proxy filings should be regarded as a reliable source of data because, like all proxy filings, they are subject to potential liability under SEC Rule 14a-9 if they contain statements that are false or misleading, or if they omit a material fact. In short, if a company claims that an advisors’ recommendation is factually or analytically wrong, it must be prepared to substantiate that claim. [14]

Moreover, it is probably fair to say that the number of supplemental proxy filings contesting proxy advisor recommendations represent the “tip of the iceberg” since many companies with objections to an advisor’s recommendations decide not to make supplemental filings either because default electronic voting or other timing issues limit their impact on voting, or because they know they have to face the recommendations of the proxy advisor in future years. [15]

During the period examined, there were 107 filings from 94 different companies citing 139 significant problems including 90 factual or analytical errors in the three categories that we analyzed. There were 39 supplemental filings claiming that the advisors’ reports contained factual errors, while 51 filings cite analytical errors of varying kinds. Serious disputes were expressed in 49 filings. Some filings expressed concerns in more than one category, with several expressing objections in all three categories. A hyperlink to the tabulated results appears here.

Perhaps the most ironic filing was made on June 1, 2017 by Willis Towers Watson. [16] The company took issue with an ISS report challenging the design of its executive compensation program. In short, Willis Towers Watson objected when ISS sought to substitute its judgment about compensation plan design for that of a company widely regarded as a leading expert on that very topic. The filing cited a litany of factual errors and laid bare the lack of depth in the ISS analysis–demonstrating that ISS had perhaps unwisely brought a knife to a gun fight.

Other filings were less entertaining, but often no less troubling. Standing back and looking at the body of these supplemental filings leads to the conclusion that a meaningful number of public companies have been willing to go on the record identifying real problems in their proxy advisory reports.

Conclusion

The report and the surveys discussed in this post strongly suggest that the concerns expressed by public companies and industry groups about proxy advisors should not be dismissed. Policy makers should explore and implement legislative or regulatory measures to assure that:

- Funds with fiduciary duties to their beneficiaries are not placing undue reliance on the recommendations of third parties;

- Institutional investors are making fully-informed voting decisions;

- Investors have more transparency into how their votes are to be cast on a default basis; and

- Public companies are allowed a reasonable opportunity to identify and respond to defects in the analysis of third-party proxy advisors.

Endnotes

1Available at: https://www.blackrock.com/corporate/literature/whitepaper/viewpoint-investment-stewardship-ecosystem-july-2018.pdf(go back)

2Blackrock reports that it employs over 30 professionals dedicated to reviewing proxy proposals. The investment made by Blackrock and similar companies should serve as a model for the type activity needed for investment managers to exercise their fiduciary voting duties.(go back)

3Rating the Ratings: How Good are Commercial Governance Ratings: Robert Daines, Ian D. Goe and David F. Larcker, Journal of Financial Economics, December 2010, Vol. 98. Issue 3, pages 439-461.(go back)

42015 Investor Survey: Deconstructing Proxy Statements—What Matters to Investors, David F. Larcker, Ronald Schneider, Brian Tayan, Aaron Boyd. Stanford University, RR Donnelley, and Equilar. February 2015.(go back)

5Available at: https://www.issgovernance.com/file/duediligence/20180530-iss-letter-to-senate-banking-committee-members.pdf(go back)

6See, ISS March 5, 2014 letter to the SEC, available at: https://www.sec.gov/comments/4-670/4670-13.pdf(go back)

7See ISS letter to SEC dated August 7, 2018 available at: https://www.sec.gov/comments/s7-09-18/s70918-4184213-172552.pdf(go back)

8Marriage, Madison. “BlackRock, Vanguard and State Street bulk up governance staff,” Financial Times, 28 Jan. 2017.(go back)

9This robo-voting procedure was described in detail in the August 3, 2017 letter of the National Investor Relations Institute to SEC Chair Jay Clayton, available at: https://www.niri.org/NIRI/media/NIRI-Resources/NIRI-SEC-Letter-PA-Firms-August-2017.pdf(go back)

10Testimony of Darla C. Stuckey, President & CEO, Society for Corporate Governance, Committee on Banking, Housing , and Urban Affairs Hearing on “Legislative Proposals to Examine Corporate Governance” (June 28,2018), U.S. Senate, available at: https://www.banking.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/Stuckey%20Testimony%206-28-18.pdf.(go back)

11Glass Lewis Response To SEC Statement Regarding Staff Proxy Advisory Letters, (September 14, 20188), available at: http://www.glasslewis.com/glass-lewis-response-to-sec-statement-regarding-staff-proxy-advisory-letters/(go back)

12Testimony of Katherine H. Rabin, CEO, Glass Lewis & Co, Subcommittee on Capital Markets and Government Sponsored Enterprises, U.S. House of Representatives, (May 17, 2016) available at: http://www.glasslewis.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/2016_0517_Glass-Lewis-HFSS-Testimony_FINAL.pdf.(go back)

13SEC Request for Comments, July 14, 2010, available at: https://www.sec.gov/news/press/2010/2010-122.htm(go back)

14This accountability stands in stark contrast to the fact that ISS and GL have experienced no regulatory consequences for issuing incorrect reports.(go back)

15Picker, L & Lasky, A. “A congressman calls these Wall Street proxy advisory firms ‘Vinny down the street’ for their power to pressure companies,” CNBC, 28 June 2018.(go back)

16Willis Towers Watson Public Limited Company, Proxy Statement to the SEC, June 1, 2017 https://www.sec.gov/Archives/edgar/data/1140536/000119312517189751/d380806ddefa14a.htm(go back)

Print

Print