Kosmas Papadopoulos is Managing Editor at ISS Analytics. This post is based on an ISS Analytics memorandum by Mr. Papadopoulos.

For the better part of this decade, governance practitioners and investors have paid significant attention to the issue of board refreshment. Their primary concern is that a stale board—one that has not added new members for many years—may become complacent, whereby a lack of independence, new perspectives, and diversity could pose significant risks in relation to long-term performance and effective oversight of management.

The argument that board renewal practices help companies better manage risk and performance is validated by the data. In this article, we find that companies with a balanced board composition relative to director tenure tend to show better financial results and have a lower risk profile compared to their peers. At the same time, companies whose directors’ tenure is heavily concentrated (whether mostly short-tenured or mostly long-tenured) exhibit poorer performance and have a higher risk profile. Therefore, as an extension beyond practicing basic board refreshment, companies may gain significant benefits by maintaining a balance of experience and new capacity on the board.

The global landscape of board refreshment practices

Recognizing the importance of board refreshment, many national governance codes consider excessive director tenure as a factor that could compromise independence; hence, companies are required to disclose clear rationales when appointing long-tenured directors as independent members of the board. In the early 2000s, the United Kingdom was the pioneer of such provisions, and many European and Asian markets have followed suit. Meanwhile, some investors have created screens for flagging excessive board tenure either at the director level or as part of a holistic evaluation of board composition.

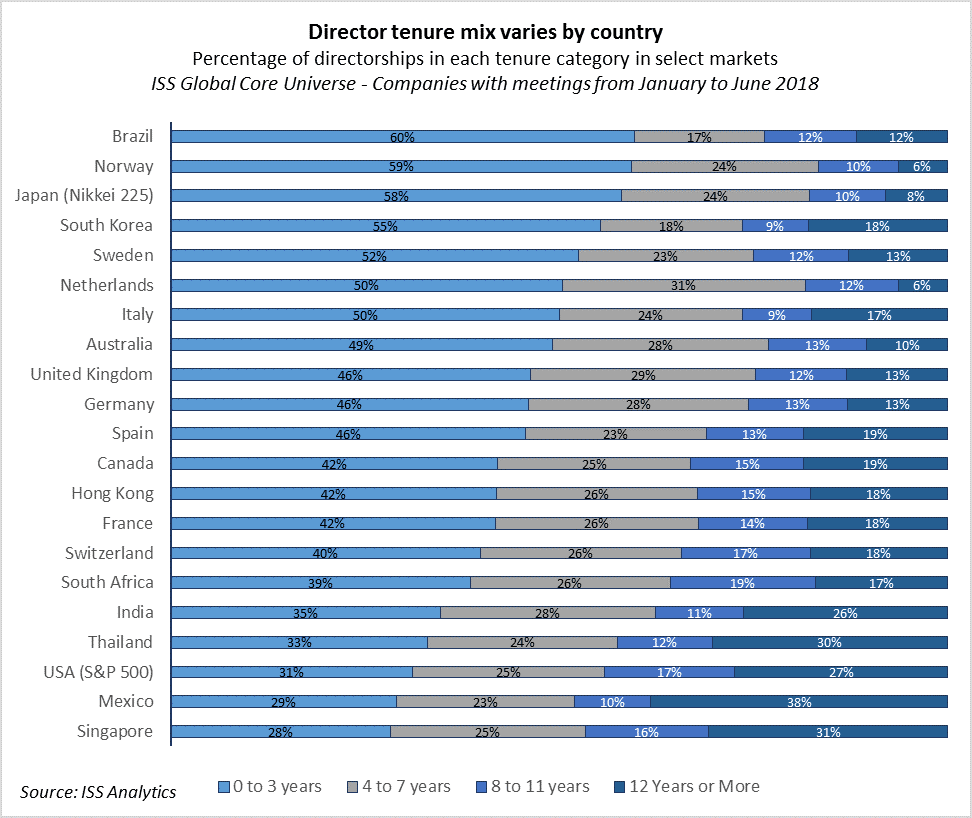

The graph above demonstrates that recent director appointees make up a significant proportion of directorships across the globe, as directors with a tenure of zero to three years range from 28 percent of board memberships in Singapore to 60 percent in Brazil. There are multiple reasons for the wave of new director appointees in the various markets. First, several countries (like Japan, Brazil, and France) revised their governance codes to require higher independence standards, prompting the appointment of new outside directors.

Many of these governance codes stipulated specific provisions linking board tenure to board independence, an approach which has reinforced higher board turnover in these markets. In addition, recent government mandates and investor pressure for greater gender diversity encouraged the nominations of new women directors. Finally, in markets like Brazil and South Korea, corruption scandals fueled investor and public outrage, leading to board overhauls in many of those countries’ largest corporations.

Digging deeper, several factors contribute to a larger number of tenured directors. Markets that do not have regulatory standards restricting tenure, like the United States and Mexico, tend to have higher percentages of directors with long tenure. Ownership structures also play a role in tenure composition, as countries with closely-held and/or family-owned firms, like India, Thailand, Mexico, and Singapore, tend to have higher percentages of tenured directors, who typically are members of the founding family or representatives of the controlling shareholder.

Boards try to find the right balance on refreshment

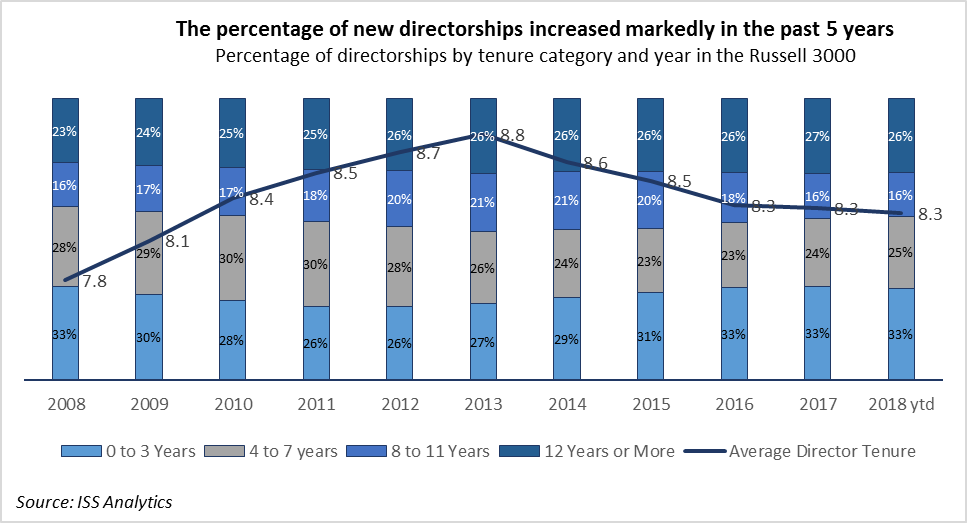

In the United States, market forces, not regulatory intervention, have driven the evolution of board refreshment. Shareholder engagement, including the implementation of more stringent voting policies by some prominent asset managers and asset owners, and an increased focus by directors themselves on board tenure, diversity, and skills, brought board refreshment to the forefront. The percentage of new directors, defined as those with up to three years on the board, increased from approximately one-quarter of director nominees in 2012 to one-third of director nominees in 2018.

Interestingly, the percentage of long-tenured directors, defined as those with 12 years or more on the board, remained steady throughout this period and stands higher compared to a decade ago. It would appear that companies try to strike a balance of retaining experienced directors, while introducing fresh perspectives, backgrounds, and skillsets through the nomination of new board members. Therefore, the ultimate objective for both boards and investors is not simply the frequent turnover of the directors but rather a healthy balance that combines experience and continuity with new capacity.

Tenure balance and company performance

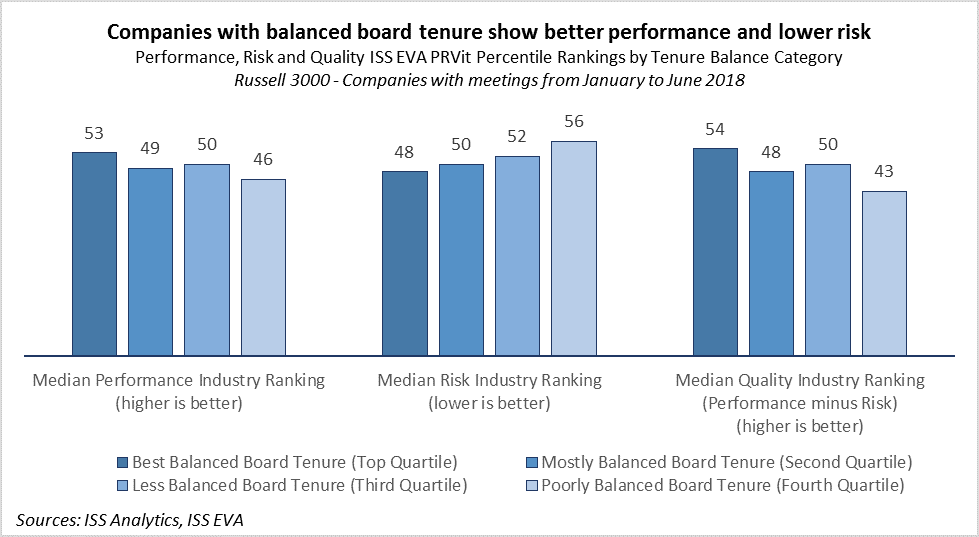

In an effort to measure tenure balance, we ranked companies based on the degree of equal distribution of directorships among the four tenure categories used in the graphs above: 0 to 3 years (new directors), 4 to 7 years (medium-tenured directors), 8 to 11 years (experienced directors), 12 years or more (long-tenured directors). Based on the distributions in each tenure category for each company, we separated Russell 3000 companies with meetings from January to June 2018 into four quartiles:

- Best Balanced Board Tenure: Companies whose directors are fairly equally distributed among the four tenure categories.

- Mostly Balanced Board Tenure: Companies who generally have directors in all tenure categories with slight concentrations in certain tenure groups.

- Less Balanced Board Tenure: Companies whose directors tend to be concentrated in one or two tenure categories.

- Poorly Balanced Board Tenure: Companies whose directors are heavily concentrated in one or two tenure categories.

Additionally, we examined the relationship between tenure balance and company performance. Our research indicates that a balanced board tenure seems to pay off in terms of financial performance and the risk profile of the company. As a measure of performance and risk exposure, we use underlying components of the ISS EVA PRVit score methodology, whose key components include the percentile ranking of companies among industry peers according to financial performance (profitability and growth momentum), risk profile (volatility of earnings and stock price, as well as balance sheet exposure), and overall performance quality (combination of performance and risk).

We see a strong correlation between board tenure balance and performance, as well as an inverse relationship between board tenure balance and risk. Companies whose boards had relatively equal representation across all categories of the tenure spectrum tended to rank higher in financial performance and had a lower risk profile compared to the rest of the market. Meanwhile, companies with directors concentrated in one or two tenure categories exhibited the worst performance and the highest risk profile.

Within the group of boards with poorly balanced tenure, companies whose board members were mostly new were ranked the worst both in terms of performance and risk, while boards with a higher concentration of long-tenured directors ranked at par with the market median. This trend reflects the reactive nature of board overhauls. Wells Fargo & Co. is a notable example among this group of companies. The company’s board has been transformed following the fraud scandal that broke out in 2016, while the firm is still trying to recover from the negative effect on performance.

How to find the right tenure balance

Managing board renewal is no easy task. Renewing for the sake of renewal can be more detrimental than beneficial as boards need directors with appropriate competencies to improve board performance and promote director readiness amidst evolving market and industry dynamics. Companies and investors seem to be equally wary of arbitrary rules such as mandatory retirement ages and tenure limits. Only 18 percent of Russell 3000 firms and 31 percent of S&P 500 firms employ mandatory retirement age policies, while less than five percent of companies in both indices have maximum tenure limits in place. While such policies can sometimes help companies avoid difficult conversations about certain directors’ contributions, they also restrict directors’ flexibility in the board renewal process. Below we identify three key strategies to proactively manage board composition.

- Conduct annual individual director evaluations that consider the needs of the company. A robust board and director evaluation process can help measure both group and individual performance. Such board assessment programs may also include an external component, whereby a third party conducts an independent assessment once every three years or so.

- Review and assess director skills in the context of long-term strategy and an evolving market environment.A specific focus on skills relevant to the changing needs of the company can enable boards to recruit directors with the acumen to address new problems. The 2018 season has shown that director experience in human resources, data security, and risk management may prove advantageous in the wake of the #MeToo movement, data privacy scandals, and cybersecurity threats.

- Establish board renewal and succession programs with medium- and long-term goals. A board renewal program with specific goals creates a framework that allows the board to plan and target its refreshment and tenure balance to specific objectives, while offering greater flexibility compared to term limits or mandatory retirement age policies. For example, companies can set a target of nominating a minimum of one new director to the board every three years, or they can annually benchmark progress against an optimal board tenure composition.

Print

Print