Kathryn Neel is managing director, Seymour Burchman is managing director, and Olivia Voorhis is an associate at Semler Brossy Consulting Group, LLC. This post is based on a Semler Brossy publication by Ms. Neel, Mr. Burchman, and Ms. Voorhis.

Related research from the Program on Corporate Governance includes Excess-Pay Clawbacks by Jesse Fried and Nitzan Shilon (discussed on the Forum here), and Rationalizing the Dodd-Frank Clawback by Jesse Fried (discussed on the Forum here).

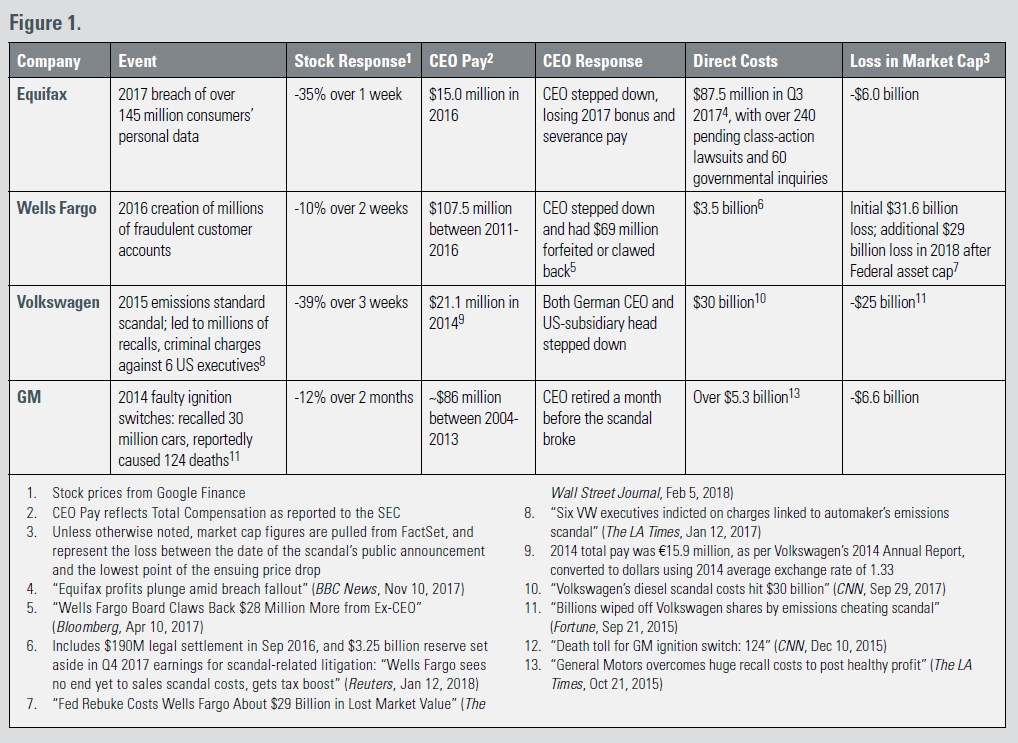

In the world of corporate governance, a string of recent corporate scandals has highlighted the criticality of effective risk management and the potential financial and reputational harm that can result from inappropriate actions or ineffective oversight (see Figure 1).

The executives of these companies received large pay packages for their stewardship and leadership, largely provided in the form of performance-based compensation under the mantra of “pay for performance.”

This raises two questions:

- What should happen if pay is delivered for performance that collapses after the payout is made, and the collapse was a consequence of actions taken when pay was earned?

- Under what conditions is it appropriate to enact a clawback, essentially a reclaiming, of incentive pay, or the cessation or recoupment of severance, and how should it work?

In response to the 2008 financial crisis, the 2010 Dodd-Frank Act tried to address these questions by requiring the recovery of incentive-based compensation when a company must restate its previously issued financial statements due to a material error. However, with two recent Wells Fargo and Equifax scandals the proposed regulations would not have applied, and yet the companies incurred major

damage through reputational harm, fines and/or legal settlements.

Accordingly, a strong business case often exists for thinking about clawbacks more broadly than regulators require. This case is derived from the typical objectives for clawback policies: protecting company and shareholder interests in the event of significant damage to the company, avoiding bad optics for the company and the board, and reducing potential motivation for inappropriate actions or decisions by reducing financial gain to be realized by executives.

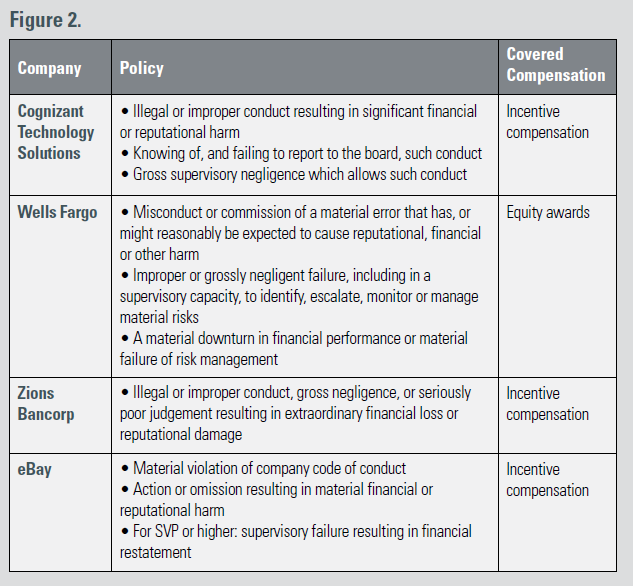

Many companies already maintain clawback policies that go beyond financial re-statements to cover detrimental conduct more broadly, particularly in industries where the potential for reputational or economic harm is high, such as financial services.

Figure 2 provides four examples of detrimental conduct policies. Some of the triggering factors not found in the typical clawback policy include general fraud or misconduct, gross negligence (even in a supervisory role), and “seriously poor judgement” if the company suffers extraordinary damage.

Accountability in these companies goes beyond intentional actions/decisions to encompass other failures, so that their clawback policies support a broader approach to risk management.

From these examples, and others, arise a set of guiding principles for framing clawbacks:

- Being fair, but also ensuring accountability.

- Penalizing actions/decisions that result in material harm to a company’s stakeholders (shareholders, customers, suppliers, employees, or the community) which involve one or more of the following:

- Misconduct, or violation of the company’s policies.

- Executive negligence or demonstrated poor judgment or leadership (willful or otherwise).

- Covering up harm that was done, even if poor judgment was not involved in the initial decision or action.

- Having an explicit set of rules governing the use of discretion, given that discretion is invariably required.

How and when should a company evaluate whether its current policy is appropriate or should be expanded? The best way may be in conjunction with a company’s annual review of material risks.

In addition to identifying the potential scenarios and major enterprise risks that would seriously harm the company, the board should determine whether it would be appropriate to expand compensation policies to allow for clawbacks in situations such as a significant product recall, product malfunction, or data breach.

Broad clawbacks can play a crucial role in sound corporate governance. When coupled with strong leadership, the right culture, strong risk management processes, and effective oversight, they can help deter inappropriate actions and decisions that can cause considerable harm to a company and its key stakeholders. Regardless of government policy, there is indeed a strong business case for a comprehensive clawback policy.

Print

Print