Paula Loop is Leader at the Governance Insights Center, Catherine Bromilow is Partner at the Governance Insights Center, and Sean Joyce is US Cybersecurity and Privacy Leader at PricewaterhouseCoopers LLP. This post is based on a PwC publication by Ms. Loop, Ms. Bromilow, and Mr. Joyce.

Directors can add value as their companies struggle to tackle cyber risk. We put the threat environment in context for you and outline the top issues confronting companies and boards. And we identify concrete steps for boards to up their game in this complex area.

You don’t need us to tell you that cyber threats are everywhere. Breaches make headlines on what seems like a daily basis. They also cost companies—in money and reputation. Indeed, cyber threats are among US CEOs’ top concerns, according to PwC’s 20th Global CEO Survey.

The pace of cyber breaches isn’t slowing. In part, we’re making it too easy for attackers. How? Employees fall for sophisticated phishing schemes, neglect to install security updates or use weak passwords. We are also doing more work on mobile devices, which tend not to be as well protected. And companies don’t always invest enough in cybersecurity or patch their systems promptly when problems are discovered.

The nature of cyber threats is also evolving. The self-propagating WannaCry attack, for instance, could infect a computer even if the user didn’t click on the link. Indeed, 2017 saw a number of major ransomware attacks that froze computer systems—keeping some companies offline for weeks.

Despite how pervasive the threats are, 44% of the 9,500 executives surveyed in PwC’s 2018 Global State of Information Security® Survey say they don’t have an overall information security strategy. That gives you a sense of how much work companies still need to do. Overseeing cyber risk is a huge challenge, but we have ideas for how directors can tackle cybersecurity head-on.

Challenge: How can our board understand whether management’s cybersecurity and IT program reduces the risk of a major cyberattack or data breach—or actually makes the company more vulnerable?

Many directors are not confident that management has a handle on cyber threats. PwC’s 2017 Annual Corporate Directors Survey found that only 39% of directors are very comfortable that their company has identified its most valuable and sensitive digital assets. And a quarter had little or no faith at all that their company has identified who might attack.

There are obviously many moving parts that management needs to get right. Many companies align their programs and investments with a cybersecurity framework to help ensure they’re addressing everything they should.

For a board to oversee cyber risks effectively, it needs the right information on how the company addresses those risks. But 63% of directors say they’re not very comfortable that their company is providing the board with adequate cybersecurity metrics. [1]

Boards also shortchange the time they give to discussing cyber risks. We often see board agendas allocate relatively little time to the topic.

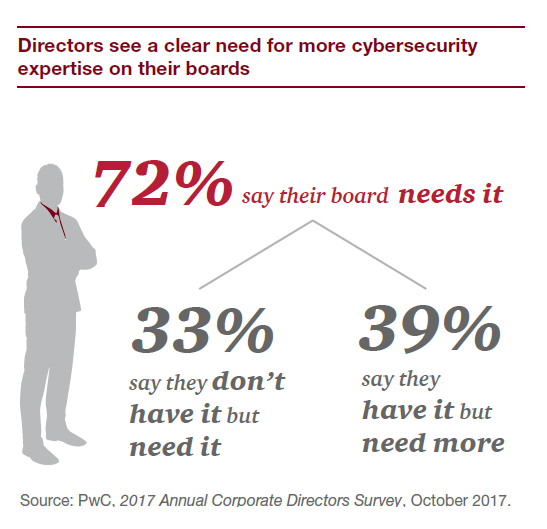

Another part of the challenge is that few boards have directors with current technology or cybersecurity expertise. And that puts directors at a disadvantage in being able to figure out if management is doing enough to address this area of significant risk.

Why does cybersecurity often break down in companies?

| Common issues | Why they matter |

|---|---|

| There’s no inventory of the company’s digital assets | Companies can’t protect assets they don’t know about. Management should be able to explain what information and data they hold, why it’s needed, where it is (within the company’s systems or with third parties) and whether it’s properly protected. They should also know which data is most valuable (the crown jewels). |

| The company doesn’t know which third parties it digitally connects with | A company may interact—and even share sensitive information—with thousands of suppliers and contractors. Hackers often target these third parties as a way to get into a company’s network. Yet more than half of companies don’t keep a comprehensive inventory of the third parties they share sensitive information with. [2] |

| The company hasn’t identified who is most likely to come after its data | Knowing who might attack helps the company better anticipate how they might attack. That in turn may help the company put up better defenses. |

| The company has poor cyber hygiene | Systems that aren’t properly configured are more vulnerable to attacks. So companies should employ leading practices, like multi-factor authentication, to protect highly sensitive information. They also need to do the basics right—like removing access on a timely basis for people who leave the company or change jobs. |

| The company hasn’t patched known system vulnerabilities | System vulnerabilities are being uncovered constantly. But not all software companies push out patches to users. So the company needs to ensure someone regularly monitors to see if patch updates are available. And then make sure those fixes get made. |

| The company has a wide attack surface | Providing more ways to access company systems makes things easier for employees, customers and third parties. And for hackers. So companies need stronger controls (such as multi-factor authentication). And they need to increase their monitoring for suspicious activity. |

| Employees aren’t trained on their role in security | Current employees are the top source of security incidents—whether intentional or not. [3] Yet only half (52%) of executives say their company has an employee security awareness training program. [4] |

| Cybersecurity is viewed as the CISO’s responsibility | A chief information security officer (CISO) can’t do the job alone. Other groups like Infrastructure or Operations need to cooperate and provide resources to address cyber issues. |

Board action: Focus on getting the right information and building relationships with the company’s tech and security leaders so you get a better sense of whether management is doing enough.

This is a really tough area to oversee. Here are a number of questions to help as you address it.

1. Since cybersecurity is really a business issue, should the full board oversee it?

Half of directors say their audit committee is responsible for cyber risk, and 16% give it to either a separate risk committee or a separate IT committee. Only 30% say it’s a full board responsibility. [5] If the full board doesn’t want to oversee cyber risk, ensure that, at a minimum, whichever committee is assigned the responsibility provides regular and comprehensive reporting up to the whole board. And consider moving it from the already overloaded audit committee to another board committee.

2. Does our board need greater cybersecurity or technology expertise?

For some companies, the answer will be to recruit a director with serious expertise in cybersecurity. But others won’t choose to close their skill gap by adding a new director. People with these skills are hard to find, especially since the technology landscape is changing so quickly. Some boards may not have room to add another member. Others may not want to add someone with such specific expertise unless they’re confident that person could handle other board matters as well. So instead they look for other ways to address any gap, including continuing education and using outside advisors.

3. Is everyone in the room who needs to be?

The cybersecurity discussion should include business, technology and risk management leaders—as well as the CEO and CFO. Why? For one, it reinforces that cyber is an enterprise-wide issue—and that directors expect everyone to be accountable for managing the risk. The discussion also may expose other areas where there are security gaps. For example, while a CISO will often cover IT, many industrial organizations also need to protect OT—the operational technology that directs what happens in physical plants or processes. So if the CISO isn’t covering OT, the board needs to hear from whoever is.

4. Do we have the information we need to oversee cyber risk?

First, consider whether you have the basic information you need on the company’s IT environment. Without this background, it’s tough to make sense of the level of risk the company faces. There are a few key areas:

- The nature of the company’s systems.

- Are they developed in-house, purchased and customized or in the cloud?

- Are any no longer supported by vendors?

- Is the company running multiple versions of key systems in different divisions?

- To what extent has the company integrated the systems of companies it acquired?

- The security resources.

- Where does IT security report?

- What are IT security’s resources and budget? How do they compare to industry benchmarks?

- Has the company adopted a cybersecurity framework (e.g., NIST, ISO 27001)?

This type of basic information doesn’t change much, so directors likely only need periodic refreshers.

On the other hand, directors will want more frequent reporting on what does change. Each company needs to figure out which items—quantitative and qualitative—are most relevant. It’s also helpful for directors to see whether management believes cyber risk is increasing, stable or decreasing.

A good dashboard gives directors an at-a-glance understanding of the state of the company’s cyber risk. There are a number of different approaches to assembling a dashboard. One is to simply classify issues between external and internal factors, like the example we show below.

If boards sense the dashboard isn’t giving a complete or accurate picture, they shouldn’t be afraid to challenge what’s presented in it. Read more to find out how.

Example of what a dashboard might look like

5. Have we built a relationship that allows the CISO to be candid with us?

The CISO has a lot of responsibility but doesn’t always have the authority to insist that other technology and business leaders fall in line. A strong relationship with the board helps the CISO feel comfortable giving directors the true picture (warts and all) of cyber risks, including his or her views on whether resources are adequate. Periodic private sessions with the CISO are a key part of understanding whether the company is doing enough to manage these risks.

6. How can we know whether the controls and processes designed to prevent data breaches are working?

Speaking to objective groups, such as internal audit, can offer the board different perspectives. The board may also want to hire its own outside consultants to periodically review the state of cybersecurity at the company and report back to the board.

- Hold deep-dive discussions about the company’s situation. That could include the company’s cybersecurity strategy, the types of cyber threats facing the company and the nature of the company’s “crown jewels.”

- Attend external programs. There are a number of conferences that focus on the oversight of cyber risk.

- Ask management what it has learned from connecting with peers and industry groups.

- Ask law enforcement (e.g., the FBI) and other experts to present on the threat environment, attack trends and common vulnerabilities. Then discuss with management how the company is addressing these developments.

Challenge: Given that companies are under constant attack, how can directors understand whether their company is adequately prepared to handle a breach?

No company is immune to the threat of a breach. One particularly scary aspect of cybersecurity is that companies may only know they’ve been breached when an outside party, such as the FBI, notifies them. Then there’s the question of what the company needs to do once it discovers a breach. Obviously it needs to investigate and patch its systems. But there’s much more.

Nearly all US states and many countries have laws requiring entities to notify individuals when there’s been a security breach involving personally identifiable information. These laws often set a deadline for notification—sometimes as short as 72 hours. The data breach notification laws change from time to time, making it a challenge to keep up to date. Separately, companies should also consider any potential SEC disclosure requirements regarding cyber risks and incidents.

Breaches can mean significant fines from regulatory agencies, as well as class-action lawsuits. They can also damage a company’s reputation and brand—resulting in loss of customers, as well as investors possibly losing confidence in the company. And as we have seen with some breaches, senior executives can lose their jobs.

Breaches also mean more costs to companies—to investigate, remediate and compensate those who were harmed. Only half of US companies have cyber insurance, [6] despite the growing number and size of incidents. In part, there’s still some skepticism on how claims will be covered.

Given how likely a breach is and how much companies need to do to respond, it’s surprising that 54% of executives say their companies don’t have an incident response plan. [7] Yet companies that responded well to a breach—thanks to better preparation—usually come out of the crisis better than those that had to scramble.

Board action: Regularly review the breach and crisis management plan and lessons learned from management’s testing.

It’s important to ask management about the company’s cyber incident response and crisis management plan on a regular basis. If there isn’t one, press management for a timeline to develop and test one.

If there is a plan, discuss what it entails and how the company intends to continue operating in the event of a disruptive attack. It should also identify everyone who needs to be involved, which could include the communications team, finance leaders, business leaders, legal counsel and the broader crisis response team, as well as IT specialists. The plan should specify which external resources are on retainer to support the internal teams. And who the company will work with on the law enforcement side.

A key part of the plan should cover breach notification and escalation procedures. When will the board be notified? What is the company’s plan to inform regulators? How and when will other stakeholders—including individuals whose personal information may have been lost—be informed?

Also ask management about plan testing and what changes were made as a result of the last test. Some directors even observe or participate in tabletop testing exercises to get a better appreciation for how management plans to address a cyber crisis.

Finally, have management explain if it has updated controls or recovery plans based on recent incidents at other organizations.

In conclusion…

As cyber threats persist, boards recognize they need to step up their cyber risk oversight. That starts when directors recognize that the responsibility for handling cyber risk goes well beyond the CISO. How? By insisting that cybersecurity be a business discussion, with the right senior executives in the room and a sophisticated understanding of the threats.

Endnotes

1PwC, 2017 Annual Corporate Directors Survey, October 2017.(go back)

2Ponemon Institute, Data Risk in the Third-Party Ecosystem, September 28, 2017.(go back)

3PwC, Global State of Information Security® Survey 2018, October 2017.(go back)

4Ibid.(go back)

5PwC, 2017 Annual Corporate Directors Survey, October 2017.(go back)

6Insurance Journal, “Why 27% of U.S. Firms Have No Plans to Buy Cyber Insurance”, May 31, 2017; http://www.insurancejournal.com/news/national/2017/05/31/452647.htm(go back)

7PwC, Global State of Information Security® Survey 2018, October 2017.(go back)

Print

Print