Paula Loop is Leader, Catherine Bromilow is Partner, and Leah Malone is Director of the Governance Insight Center at PricewaterhouseCoopers LLP. This post is based on a PwC publication by Ms. Loop, Ms. Bromilow, and Ms. Malone. Related research from the Program on Corporate Governance includes Dancing with Activists by Lucian Bebchuk, Alon Brav, Wei Jiang, and Thomas Keusch (discussed on the Forum here); Who Bleeds When the Wolves Bite? A Flesh-and-Blood Perspective on Hedge Fund Activism and Our Strange Corporate Governance System by Leo E. Strine, Jr. (discussed on the Forum here); and The Long-Term Effects of Hedge Fund Activism by Lucian Bebchuk, Alon Brav, and Wei Jiang (discussed on the Forum here).

Activism is about driving change. Shareholders turn to it when they think management isn’t maximizing a company’s potential. Activism can include anything from a full-blown proxy contest that seeks to replace the entire board, to shareholder proposals asking for policy changes or disclosure on some issue. In other cases, shareholders want to meet with a company’s executives or directors to discuss their concerns and urge action. The form activism takes often depends on the type of investor and what they want.

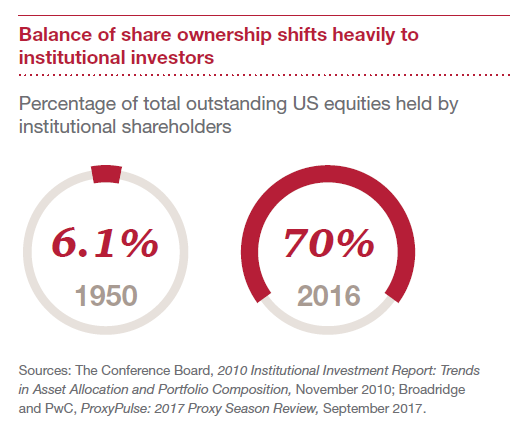

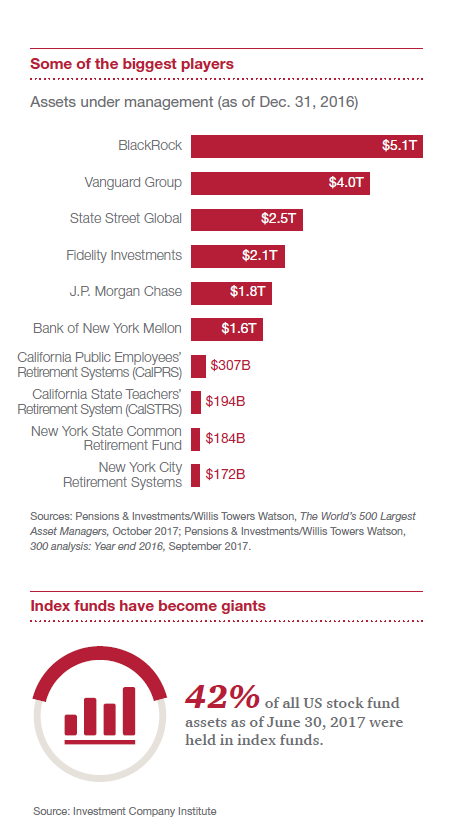

Institutional investors and hedge funds typically have the most impact. Individual investors may submit lots of shareholder proposals, but they usually lack the backing to drive real change.

To prepare for—and possibly to even avoid—shareholder activism, companies and their directors need to understand today’s landscape. Who are the activists? What are they are trying to achieve? When are activists more likely to approach a company? What tactics do they use? We break down the answers by the two main types of investors. Read on.

Institutional investors

These include pension funds, asset managers, mutual funds and insurance companies.

Institutional investors are normally long-term shareholders. Many hold their shares in index funds, which are popular for their low fees. Institutions that provide index funds can’t just sell a position if they think a stock is underperforming, or if they believe the company’s governance practices hinder it’s long- term value. And so they turn to activism. Through activism, they can bring attention to their concerns and drive the change that they believe will create long-term value—including through changes in corporate governance practices. Institutional investors such as Vanguard are vocal about their belief that companies with strong corporate governance practices can deliver better value in the long run. [1]

Shareholder engagement

When institutional investors have concerns, they often start by engaging one-on-one with the company. In prior years, engagement was mostly between the portfolio manager and the company’s investor relations team or members of management, and focused largely on company performance. Today, investors’ corporate governance teams are often driving the meetings—sometimes alone and sometimes in combination with portfolio managers.

At times shareholders ask to meet with directors. They may have identified issues in the company’s executive compensation plans, its governance policies or practices, or its strategic plan. Other times, shareholders are looking to lay the foundation of an open dialogue with the directors. So when issues do arise in the future, they have an existing relationship upon which to build.

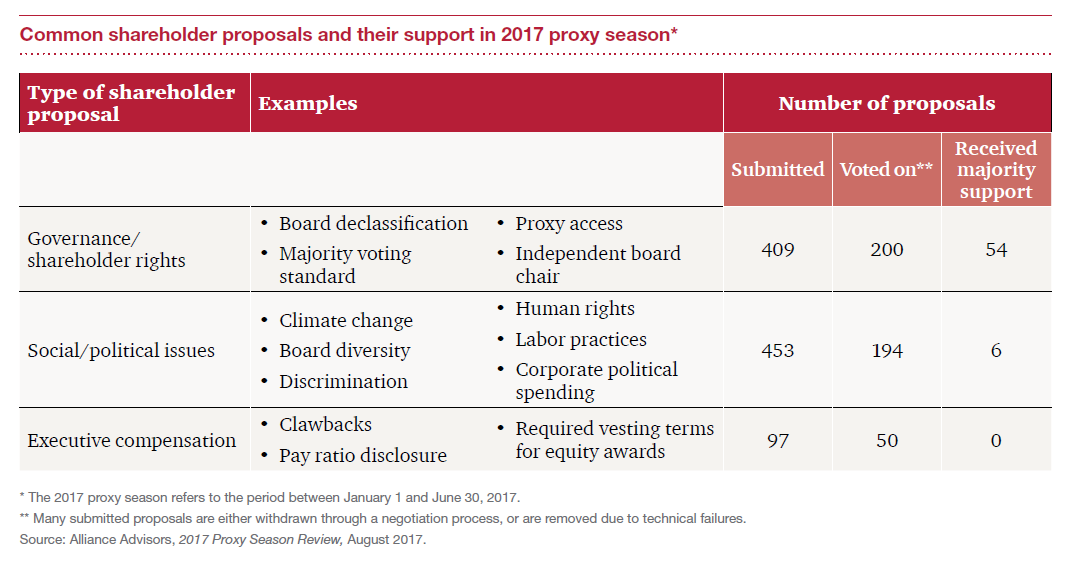

Shareholder proposals

In some cases, institutional investors submit—or indicate they plan to submit—a proposal if direct engagement with the company and its directors doesn’t produce changes. Other investors view a shareholder proposal as a way to begin the conversation with a company.

These proposals often focus on governance practices or policies, executive compensation, or the company’s behavior as a corporate citizen. Proponents watch how the major institutional investors are voting on issues, and have a sense of which shareholders may be likely to support their proposal going in. Investors also often reach out to other shareholders to encourage support for their measure. By the time a company even receives a shareholder proposal, its sponsor may already have a sense of whether it will pass.

Proxy access: a highly successful campaign

Proxy access allows certain shareholders to include their director nominees in the company’s proxy statement

Institutional investors have been pushing for proxy access for years through shareholder proposals. In the 2012-2014 proxy seasons, these proposals got limited support. But in the fall of 2014, the New York City Pension Fund helped proxy access to take hold through its Boardroom Accountability Project. It targeted more than 70 major public companies with a coordinated, highly public effort. Most proposals passed, and companies started to implement proxy access bylaws. Efforts have continued since then, and by mid-2017, 60% of the S&P 500 had proxy access bylaws in place.

Why does this matter now? The New York City Pension Fund has launched version 2.0 of its Boardroom Accountability Project for 2018. This time, they are taking on board diversity and renewal, calling on companies to disclose the race, gender and skills of their directors in a standard matrix format.

“Vote no” campaigns

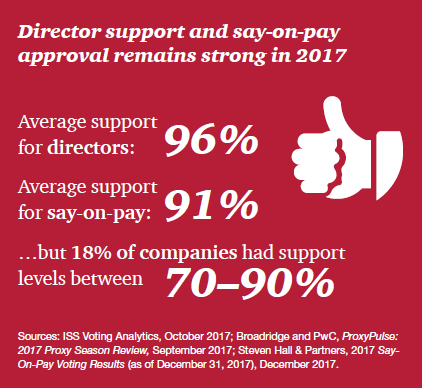

“Vote no” campaigns urge shareholders to withhold their votes from director candidates or to vote against a company’s say on pay.

The vote doesn’t actually have to fail for a vote no campaign to be a success. Overall shareholder support both for directors and for say on pay is typically above 90%. So if support levels fall to the 60s or 70s, it sends a stark message about shareholder dissatisfaction. It also generates media scrutiny, and can affect a director’s reputation. Directors often serve on multiple boards, and low support levels at one company can affect how that director is viewed at his or her other companies as well.

A vote no campaign can send a strong signal about shifting shareholder priorities. Just as proxy season was beginning in 2017, State Street Global Advisors (SSGA) used the tactic to shine a spotlight on gender diversity. They announced they would start voting against nomination and governance committee chairs at companies that didn’t have any women directors and weren’t making efforts to add them. Indeed, SSGA voted against directors at over 400 companies in 2017, sending a clear signal.

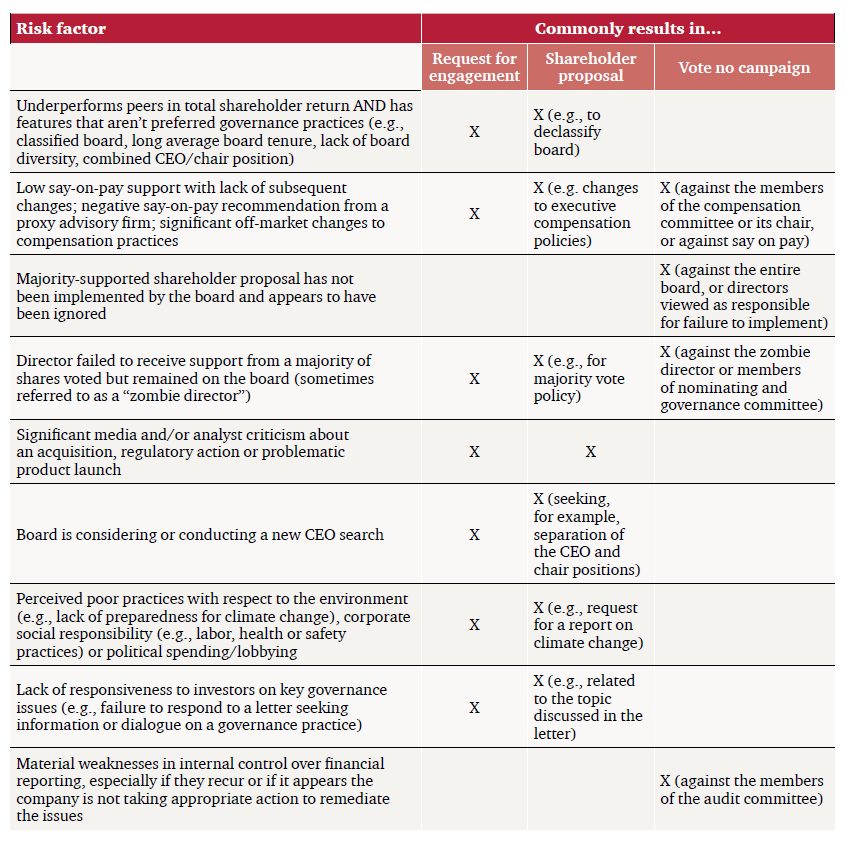

Risk factors

Different types of shareholder concerns lead to different approaches. Although these methods can seem like escalation tactics, different investors simply prefer to start in different places and may adopt more than one approach on a given issue.

Preparing for and responding to institutional investor activism

- Start a pattern of regular director engagement. Before the company receives a shareholder proposal or is targeted by a vote no campaign, start getting directors involved in discussions with major investors. Some investors view a shareholder proposal as a way to begin a conversation with the board. But if the lines of communication are already open, shareholders may not feel they need to resort to a shareholder proposal or other means.

- Respond directly to the investor. If you have received a shareholder proposal or been targeted for a vote no campaign, reach out to the investor. Discuss their specific concerns. When dealing with a shareholder proposal, the company and the shareholder may be able to agree on some action at the company in exchange for withdrawal of the proposal. Shareholders don’t always insist on immediate action. They know change can take time, and often they are satisfied if the company demonstrates that it has a plan in place to address the issue. Communication might not put an end to a vote no campaign, but understanding the shareholder’s perspective will help the company respond.

- Reach out to other shareholders. A shareholder proposal or a vote no campaign can be an opportunity to discuss the issue with other shareholders. Take the chance to articulate the company’s view about why its current course is in the best long-term interests of the company and all of its investors. And consider disclosing the breadth of the company’s shareholder engagement efforts in the proxy statement to give yourself credit for your outreach. For more on shareholder engagement, take a look at our paper Director-shareholder engagement: getting it right.

Blurring the lines—The future of institutional investor activism

Some institutional investors are moving beyond their traditional tactics. With many committed to long-term passive investments in a broad portfolio of companies, they are looking hard for ways to find untapped value at those companies—by encouraging governance changes, and otherwise. And so today, some are engaging in what has traditionally been thought of as hedge fund activism. Long-term institutional investors who previously never would have considered themselves “activists” are getting into the fray. Some are approaching hedge funds with a specific target in mind, backed by their own research, to suggest teaming up. Others are turning into “occasional activists” in their own right, without a hedge fund partner.

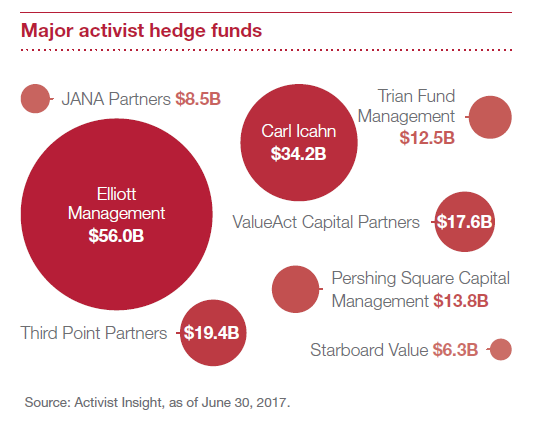

Hedge funds

Hedge funds attract big dollars from investors looking for above-average returns. So they are always looking for untapped value. Hedge fund activists often see that untapped value in the way a company is run, or the strategy it pursues. They see ineffective management, a stale board, or a company missing out on new opportunities. They see the potential for a new capital allocation strategy or changes in operations that will increase share value. And when their efforts to engage with executives or directors about these ideas fail, they often try to elect different directors.

Hedge fund activism today

Hedge fund activists used to focus mostly on capital allocation issues, such as dividends and share buybacks. Many then began looking for company combinations and break-ups—mergers, carveouts and spin-offs. Now, there is a greater focus on operational activism, which has more of a long-term focus. Activists join the board (or appoint independent directors), replace members of management and help execute a new strategy. While many hedge funds had been thought of as being too focused on short-term gains, the longer-term operational activism has helped to shift that perception.

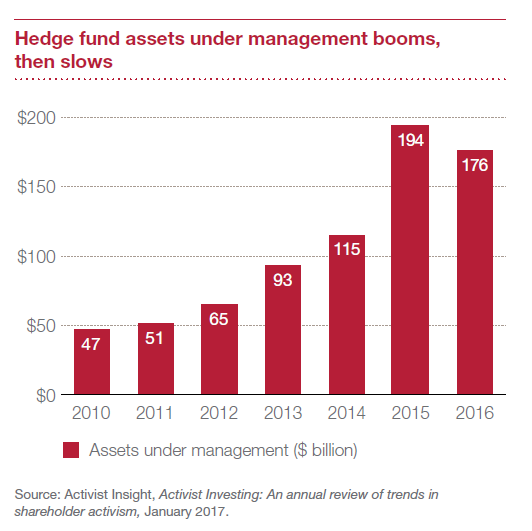

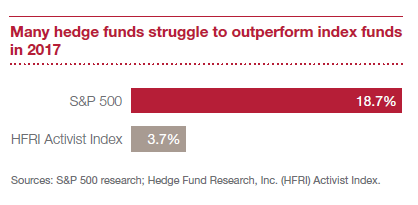

While a few hedge funds made significant profits for their investors in 2017, most have failed to outperform the S&P 500. For many investors, these returns don’t justify the high related fees, and so some large institutional investors such as the California Public Employees’ Retirement System (CalPERS) have pulled their investments out of hedge funds entirely. In 2016, hedge funds actually closed at the fastest rate since the 2008 financial crisis. [2]

With competition for investments growing tighter, hedge funds are under greater pressure to post returns, which may be driving up activism even more.

Activism tactics

Some activists follow a standard playbook. Many first spend time talking to the company, highlighting areas for improvement and value creation. If they can’t negotiate a consensus around specific changes, they may move on to a proxy contest or a public media campaign.

Again, not all hedge funds follow this trajectory. Some move first to a media campaign or some other way of making a major splash. Whatever approach, hedge funds may also have spent time talking with some of the company’s key shareholders to gauge their level of support for the campaign.

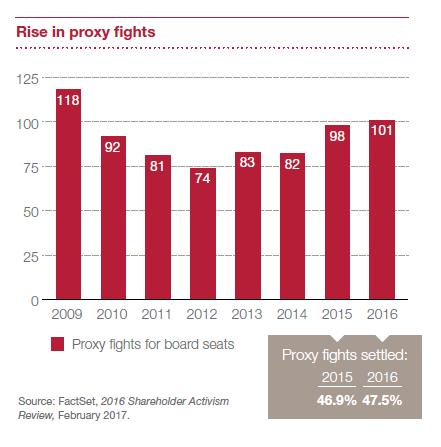

The number of proxy fights in 2016 reached its highest level since 2009, and companies are more willing to settle with activists than ever before. Proxy fights are long, expensive and draining for a company. There is greater recognition that the directors nominated by activists can sometimes add real value to the boardroom. So for many companies, it’s just not worth the cost and distraction of a proxy fight.

Settlements have now become so common, in fact, that some institutional investors are concerned that companies are settling too easily. Before rushing to settle, they urge companies to at least reach out to their significant shareholders to solicit their views. Sometimes these investors might agree with the activist—and sometimes they might want the company to hold their ground against the activist.

Risk factors

Hedge fund activists use proprietary processes to identify their targets. But most targeted companies have some or many of these characteristics:

- Low market value relative to book value

- Disappointing company performance compared to peers

- Profitable with sound operating cash flows and return on assets

- Excessive cash on hand

- For multi-business companies: one or more significantly underperforming business lines or business lines with markedly different growth potential

- Board composition does not meet today’s preferred governance practices (e.g., instead has long average board tenure, lack of board renewal, lack of diversity, lack of industry experience)

Before hedge fund activist campaigns occur

Companies can best anticipate, prepare for and respond to an activist campaign if they put themselves in an activist’s shoes. Here are four key steps:

- Rethink the information. Boards may get too much granular information that doesn’t highlight underperforming assets. Reassess the type of information the board receives and revamp it so it gives the full picture.

- Monitor shareholder positions and understand the activists. Ensure that the board is informed when an activist takes a significant position in the company or in an industry competitor. And make sure the board hears about broader activism trends that could affect the company in the future. Understanding what these shareholders may seek (i.e., understanding their “playbook”) will help the company assess its risk of becoming a target and help it know what tactics to expect.

- Evaluate and address your “risk factors.” Look for the ways an activist might criticize the company and its board. Examine company strategy from an outside perspective, and then test whether it’s working. Ask to hear from consultants, industry analysts or others from outside the company, to get a better understanding of how the company is seen by investors and potential activists and where its vulnerabilities are. Make sure they are giving their “unvarnished view”—one that has not been white-washed by management or by an unwillingness to give a frank evaluation.

If there are issues, take proactive steps to address them. This can reduce the chance of being an activist target and strengthen credibility with the company’s shareholders. Even if the company chooses not make any changes, going through the critical process will help company executives and directors reaffirm and articulate why they believe the company is on the right course.

- Launch an engagement plan. Once a company identifies areas that may attract activist attention, engaging with other shareholders around these topics can help prepare for—and in some cases may help to avoid—an activist campaign. Being transparent about the company’s vulnerabilities and its strategic choices can help change a shareholder’s view of the issue, and demonstrate that the board is fulfilling its oversight responsibilities. Other times, the engagement should be more about listening. We hear more and more about boards bringing portfolio managers or other investors in to share their thoughts on the company and ways they could improve—and possibly head off an activist.

Responding to a campaign

In responding to an activist, consider the advice that large institutional investors have shared with us: good ideas can come from anyone. Some circumstances may call for more defensive responses—such as litigation—to an activist’s campaign. But in general, we believe the most effective response plans have three components:

- Objectively consider the activist’s ideas. Activists usually do extensive homework before they approach a company. Based on that research, they develop specific proposals for unlocking value—at least in the short term. And they have often discussed these ideas with other shareholders. Assume the company’s institutional investors have already spent time evaluating the activist’s suggestions. Investors will expect the company’s executives and board to do the same—even when it’s uncomfortable. And it often is. The changes activists propose are not easy and they are not uncontroversial. If they were, the company would have already done them. More often, they are recommending fundamentally restructuring the company or the go-forward strategy. They might be looking for changes in the boardroom, which may feel like a personal affront to the directors around the table. Or they may be looking for a change in management, which will almost certainly feel like an attack on the CEO. But none of these ideas should be dismissed out of hand.

- Look for ways to build consensus. More companies than ever are finding ways to work with activists. By doing so, they avoid the distraction and high cost of a proxy contest. Companies might agree to change their capital allocation, or even to add new directors to the board. Sometimes a brush with an activist gives a company a welcome opportunity to refresh its board.

Activists are also motivated to reach agreement. Proxy contests are expensive— for both sides. If given the option, most activists would prefer to spend less time and money to achieve their goals. Once they agree, the activist and the company enter into a standstill agreement that sets the terms of their relationship going forward.

- Tell the company’s story. Now is the time to reach out instead of hunkering down. As we’ve said, an activist will likely be engaging with other shareholders, so it’s important these investors hear from management and the board as well. Ideally, the company already has an established relationship with those shareholders to build upon. If the company doesn’t believe the activist’s proposed changes are in the best long-term interests of the company and its owners, investors will want to know why—and just as importantly, how the company reached this conclusion. Often we hear that the suggestions activists make are ones that the company had already been considering.

If the activist and company are able to reach an agreement, investors will want to hear from executives and directors about why the changes are good for the company. Being seen as forward-thinking leaders, rather than victims of activism, can boost investor confidence.

Hedge fund activism is rarely “one and done”

When the annual meeting is over, and changes have been implemented, or the hedge fund has moved its attention to another target, it may feel like the storm is over. But the risk of additional activism doesn’t go away. The way the company responded to the activism, and the perception of the board’s independence and open-mindedness can make it a repeat target.

To get ahead of this, companies periodically refresh the four steps described earlier in the “Before hedge fund activist campaigns occur” section. By periodically assessing risk factors and engaging in a tailored and focused shareholder engagement program, the company can enhance its resiliency and strengthen its long-term relationship with investors.

Conclusion

As activism—by both institutional investors and hedge funds—continues to be strong, many think the number of campaigns could be on the upswing. These campaigns may also be more likely than ever to succeed. For companies, listening to and understanding shareholder concerns may be more important than ever.

Print

Print