Ilona Babenko is Associate Professor at Arizona State University W.P. Carey School of Business; Viktar Fedaseyeu is Assistant Professor in the Department of Finance at Bocconi University; and Song Zhang is a PhD student in Finance at Boston College. This post is based on their recent paper.

Over the last two decades, the share of corporate executives holding political office in the United States increased substantially, which resulted in large benefits for their firms and shifted the balance of power toward corporate interests

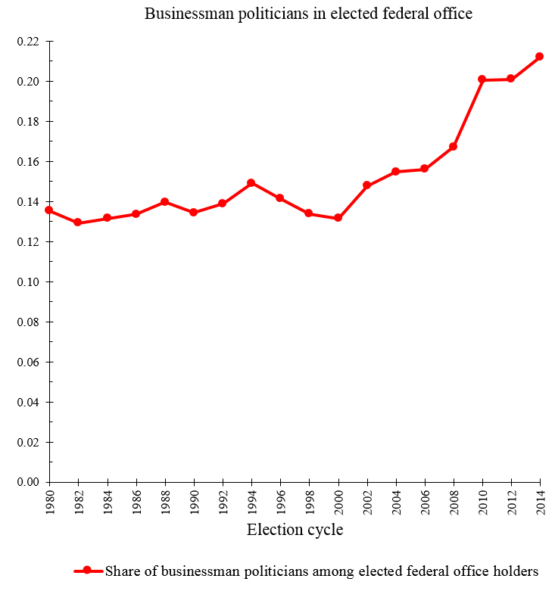

On November 8, 2016 Donald Trump won the U.S. Presidency. While his election was unusual in many respects, Trump is just one of several recent examples of corporate executives running for political office. William Harrison Binnie, a former CEO of Carlisle Plastics, Inc., unsuccessfully ran for the U.S. Senate in 2010. In 2000, Jon Corzine, a former CEO of Goldman Sachs, was elected U.S. Senator, and in 2005 became the governor of New Jersey. These examples are far from isolated. In fact, the share of federal office holders (i.e., U.S. Congressmen, Senators, and Presidents/Vice-Presidents) who had executive experience prior to being elected remained relatively flat at around 13-14% between 1980 and 2000 but then increased rather sharply to more than 21% by 2014. Why do so many executives make the switch from a career in business and run for political office? Further, how does the increase in executives’ political participation affect their firms and the legislative agenda in the United States more generally? In a new working paper, we investigate these questions by studying the incidence of corporate executives running in U.S. federal elections between 1980 and 2014.

Our first finding is that the increase in the share of executives holding federal elective office has been largely supply-driven i.e., this increase is due to a higher likelihood of businessman candidates to put their names on the ballot rather than to a higher propensity over time to win political office. In fact, the likelihood that a corporate executive runs for political office more than doubled between 1980 and 2014. While we can only speculate about the exact reasons behind this trend, this period coincided with an overall increase in political uncertainty and a larger role of government in the economy (measured by the amount of government spending). Thus, it seems plausible that that higher potential benefits from political participation for firms might have induced more executives to seek political office.

Perhaps more importantly, businessman politicians generate large benefits for their firms. We find that an average firm in our sample adds more than $390 million to its stock value around the time when its executive wins a federal election. Furthermore, some of these firm-level benefits accrue to executives directly, via personal stockholdings in their firms. An average businessman politician in our sample experiences a more than $540 thousand increase in the value of his or her holdings upon winning the election. We also find similar effects when Congress passes legislation introduced by former corporate executives. Thus, it appears that the stock market expects businessman politicians to generate large private benefits for their firms (and perhaps for themselves).

In addition to firm-level benefits, businessman politicians, to the extent that they are systematically different from non-businessman politicians, can have aggregate effects on the legislative agenda in the United States. We first document that businessman politicians appear to be less effective, in terms of their overall legislative productivity, compared to non-businessman politicians: once elected, they serve fewer terms and, as a result, introduce fewer pieces of legislation. Further, by analyzing businessman politicians’ voting records, we find that such politicians are significantly more likely, relative to non-businessman politicians, to vote for legislation supported by corporate interest groups and are less likely to vote for legislation supported by pro-consumer interest groups or labor unions. Businessman politicians are also more likely to collaborate with other businessman politicians in producing legislation, suggesting that they may be able to use their business ties to form coalitions that promote corporate interests.

Since businessman politicians may expand the ability of corporate interests to participate in the U.S. legislative process, corporations should be more likely to finance electoral campaigns of businessman politicians than those of non-businessman politicians. This is exactly what we find when we analyze the sources of campaign contributions. Corporate special interests donate substantially more funds to businessman politicians than to their non-businessman peers, whereas labor unions-linked special interests, on the other hand, donate more to non-businessman politicians.

Of course, in a democratic system, to become legislators businessman politicians must win elections. Therefore, we investigate the determinants of businessman politicians’ electoral success as well as their decision to run for political office. We find that, taking into account many other characteristics, businessman politicians have a 44% higher likelihood of winning elections in which they participate compared to non-businessman politicians. This is surprising, since we also find that businessman politicians, once elected, are not more effective than their peers at introducing and passing legislation. It appears that American voters value business experience in political candidates. We also find that executives with a better track record (proxied by the ROA of firms that they ran prior to running for office) are more likely to participate in elections. As our results show, however, corporate success does not necessarily translate into legislative effectiveness.

On the balance, we find that over the last decade businessman politicians have increased their involvement in the legislative process, and this involvement may have generated substantial benefits for their firms and shifted the balance of power toward pro-business interests.

The complete paper is available here.

Print

Print