Editor’s Note: John Avlon is a CNN senior political analyst. The views expressed in this commentary belong to the author. View more opinions at CNN.

In a political world defined by escalating confrontation, a presidential inaugural is one of the few times we slow down and listen together as fellow citizens.

These are the words that begin to define a presidency – reminding us that, at its best, politics is history in the present tense.

Not all inaugural addresses are created equal – many are too long and consequently forgettable. Others make the mistake of laying out a specific policy agenda, rather than setting a broad direction toward a new horizon.

But an inaugural is preeminently a speech about the new president’s values – about how he sees the world and America’s role in it. At best it offers a unifying vision and the promise of new beginnings.

Most are remembered – if at all – for a single phrase that becomes shorthand for the entire speech. And if you listen closely, these lines often share a similar structure. This is the one of the secrets to what makes a great inaugural address.

Thomas Jefferson called for an end to partisan rancor after the brutal 1800 campaign, declaring: “Every difference of opinion is not a difference of principle.”

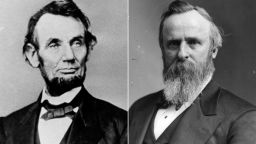

Abraham Lincoln’s second inaugural was just 701 words long, but it contained this crystalizing phrase as a guide toward reconciliation at the end of Civil War: “with malice toward none, with charity for all.”

In the depths of the Great Depression, Franklin D. Roosevelt proclaimed: “the only thing we have to fear is fear itself.”

As the greatest generation took the helm during the Cold War, John F. Kennedy declared, “Ask not what your country can do for you, but what you can do for your country.”

These are American catechism, lines that are repeated across generations, giving us a common language for our civic religion.

And there’s a pattern at work: it’s repetition of a phrase with a twist, which makes them instantly memorable. In some specific structures, it’s what’s called antimetabole, an ancient Greek word that means “turning about.”

Armed with that knowledge, listen to the most famous line from Ronald Reagan’s first inaugural: “government is not the solution to our problem; government is the problem.”

Or Bill Clinton’s: “There’s nothing wrong with America that can’t be cured by what’s right with America.”

So, it turns out there’s something like a science behind the art of great speeches.

But, of course, inaugural addresses are more than a succession of slogans.

They update the American story, connecting the past with the present and the future. The best contain a sweep of history – a clear-eyed sense of reverence for the American experiment.

And while the assembled crowds and people watching at home are celebrating the inauguration of one person to be the next president, it’s not actually about that individual leader.

He (or someday she) is simply a symbol for a new era, and his personal story – while a necessary ingredient – provides a point of contact with the American story. Still, great speeches tend to take the risk of intimacy. There needs to be a personal reveal to communicate to the heart as well as the head, and then to take that goodwill and project it forward into the future on behalf of everyone else.

Now Joe Biden’s day has finally arrived – nearly 50 years after he first arrived in Washington, DC, as one of the youngest senators and more than 30 after he first ran for president.

But Biden’s rise to the presidency was rooted in the authenticity of his own story – the middle-class kid from Scranton, Pennsylvania, who struggled through adversity and almost unimaginable loss of a wife, daughter and son. His moral authority comes not from the lifelong politician’s loquacious charm, but from his enduring heart.

While Biden is not known to be a great orator (unlike his former boss), he raised his reputation as a fighter for the middle class from the baby boom generation. His 1988 campaign speeches recalled the death of the Kennedy brothers with a determination to rekindle their idealism while railing against the outsourcing that was even then squeezing American workers. He rebounded from political stumbles over intervening decades because of a reputation for personal decency and empathy that was recognized by his colleagues across partisan lines.

Throughout the course of the 2020 campaign, he promised to “restore the soul of America” and to make government work again by governing without partisan prejudice. His best speeches – at Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, and Warm Springs, Georgia, – consciously drew on American history to summon our strength to rise above these challenging times and rediscover the better angels of our nature.

These speeches were too deep-seated in Biden’s soul to be put aside for something entirely fresh for Inauguration Day. He is not one for reinvention, and this is not a time for more reality television.

Few presidents have entered the Oval Office facing more stark challenges, from a nation violently divided along partisan lines to a pandemic still raging at its deadliest levels. Biden has not promised these problems will be solved in his first 100 days; instead he’s honestly warned that our most difficult days might still be ahead.

But it’s the endurance of hope that animates and which may inspire his inaugural address. To quote from one of his favorite poets, Seamus Heaney: “History says don’t hope on this side of the grave / But then, once in a lifetime / The longed-for tidal wave / Of justice can rise up / And hope and history rhyme.”

The rhyming of hope and history are what great inaugural addresses deliver. And rarely in our country’s history have we been more in need for such rebirth and redemption.