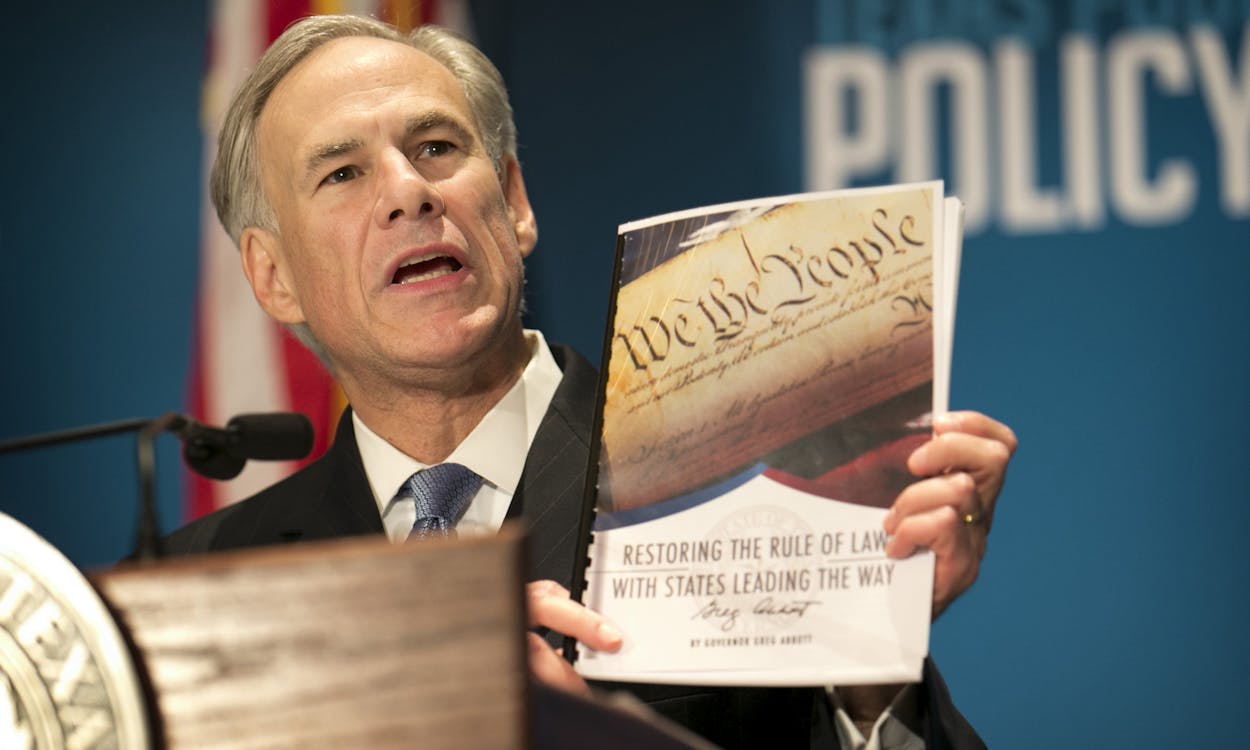

In the days leading up to Greg Abbott’s keynote address at the Texas Public Policy Foundation’s annual Policy Orientation last week, the governor’s office promised a major announcement. And as we now know, they weren’t kidding. On Friday, Abbott announced that he was adding another item to his legislative agenda: a convention of the states. In other words, he wants the Lege to pass a bill that would authorize Texas, if joined by 33 other states, to participate in a constitutional convention. Specifically, Abbott explained, he’s proposing a convention of the states to consider “the Texas plan”—nine constitutional amendments designed to rein in the federal government and restore the balance of power between the states and the United States.

This was, obviously, a controversial announcement. The Constitution, in Article V, says that constitutional conventions may be called in two ways: by two-thirds of the members of both houses of Congress, or by the legislatures of two-thirds of the states. The idea of a “convention of the states” has been simmering for several years, and a handful of states have taken steps in that direction. Last year, in fact, a resolution calling for one was backed by several dozen conservative legislators in Texas. And Abbott is not the first Republican leader to back the idea. At the beginning of the week, Marco Rubio, the Florida senator, had published an op-ed declaring that he would promote a convention of the states if elected president.

Abbott’s call, however, is more serious than any that have preceded it. His announcement was accompanied by a 90-page proposal, which makes a detailed case for both the convention and the nine amendments he’s proposing. His arguments are backed by indisputable constitutional expertise; prior to becoming governor, he spent a total of nearly twenty years as a justice on the Texas Supreme Court and as Texas attorney general. As governor of Texas, Abbott is in a position to advocate this idea in a meaningful way. The same can’t be said of Rubio; he can promote the idea all he wants, but even as a president, he would have no formal power to encourage or thwart a convention of the states. The timing, meanwhile, makes it hard to dismiss Abbott’s proposal as a pure pander: In December, Matt Bevin was sworn in as governor of Kentucky, meaning that there are currently 32 Republican governors in the United States, and two independents. In other words, 34 states—or two-thirds, as Article V requires—are led by non-Democratic governors.

And having watched Abbott’s speech in person: this is not Jade Helm. Abbott has engaged in his fair share of pandering this year, at times clumsily so. It’s easy to forget—in light of his nearly 20-point margin of victory in the 2014 elections, and his evident relish for a good fight as attorney general—that the governor has relatively little experience in political combat. During the 84th Legislature, he sometimes seemed unsure of himself; when speaking to conservative crowds Abbott sometimes came across as a smart person self-consciously trying to simulate a fire-breathing attitude about popular concerns. That was not the case Friday. This was the best speech I’ve ever seen Abbott give. From the moment he took the stage he was full of swagger, and there was nothing feigned about his ferocity as he made the case for such a convention.

The Texas plan was bound to elicit debate, and I have no doubt the governor is looking forward to that; as he said in his opening remarks, there are some things he misses about his old job.

Those factors helps explain why many Democrats were outraged by Abbott’s announcement; on the left, the governor’s announcement was received as an example of crypto-secessionist right-wing lunacy. It was perceived as pandering to the same sense of persecution, resentment, and entitlement that has propelled Donald Trump to the front of the Republican presidential primary. That may also explain why so many Republicans were seriously conflicted. It’s hard to imagine a more receptive audience than the one Abbott had. As Patrick Michels put it, at the Texas Observer, “many of the Texas Legislature’s hottest conservative fantasies begin with TPPF”; some of TPPF’s scholars have, in fact, been advocating for a convention of the states. All the same, the idea is one that inspires genuine angst on the right—and as a result of Abbott’s proposal, it can no longer be dismissed as an academic debate.

Personally, though, I thought it was a great speech, and I emerged into the sunny winter afternoon with a youthful buoyancy that I haven’t felt about Texas politics in more than a year, for several reasons.

What Abbott has done, essentially, is call for a debate that is well worth having. I understand why the Tenth Amendment is held in ill repute; it establishes states’ rights vis-a-vis the federal government, and historically those have been invoked to justify all manner of sins. All the same, the Tenth Amendment exists. It protects Massachusetts and California just as much as Texas and Alabama; and it will continue to do so, barring changes to the Constitution, which Democrats are apparently not eager to pursue. That being the case, I don’t see the harm in having a debate over its purpose, scope, and meaning. It’ll be interesting, if nothing else, and it may even be productive.

Along the way, we can expect a serious discussion about attendant issues such as executive power. In his speech, Abbott criticized all three branches of the federal government. He pointed to Barack Obama’s executive actions as an example of unconstitutional overreach, but also argued that Congress has exceeded its constitutional parameters, and labeled the Supreme Court a “co-conspirator,” which has “quite embarrassingly,” in his view, strained to rewrite laws rather than merely ruling on them. Democrats, of course, will dispute his motives. Since Obama first took office, in 2009, many have dismissed constitutional objections to various executive orders, or to Supreme Court rulings on matters related to Obama, as specious and ideologically motivated. But we’re in the final year of Obama’s presidency. Any new constraints on executive power that emerge from a convention of the states–or any new understanding of the extant limits of executive power that may emerge from the debate Abbott is calling for—will apply only to Obama’s successors. If that president is Cruz, Democrats may be glad for it. If the president is Donald Trump, we all will.

Less honorably, I think these debates are going to be fun. I’ll admit that I’m among the Americans who finds it highly annoying that so many Democrats have spent the past seven years dismissing most criticism of Obama as ipso facto invalid. It’s true that he is America’s first black president and many Republicans have treated him very unfairly. It’s also true, as Abbott said Friday, that John Roberts had no business re-describing the Affordable Care Act’s individual mandate as a “tax.” If mandate were a tax, the Congressional Budget Office would have scored the law quite differently. And although I would have liked to see Congress pass comprehensive immigration reform in 2013, the fact that it failed to do so is not, as Abbott also said, a justification for Obama’s subsequent executive actions on the subject. From a constitutional perspective, legislative “obstruction” is a predictable result of the separation of powers; checks and balances are a feature, not a bug.

Abbott, it’s worth noting, was elected attorney general in 2002. He was fighting the federal government before Obama even ran for Senate. His signature accomplishment on that front, which Ted Cruz shares as the solicitor general who argued the case at the Supreme Court, was 2007’s Medellin v Texas—the eventual result of an order from George W. Bush. So the governor is well equipped to lead American conservatives in calling for a convention of the states. He’s already begun, with a pre-emptive riposte to potential critics in the plan itself: “As an initial matter, the Texas Plan and the need for a constitutional convention cannot be dismissed as ‘radical.’” The ground rules for constitutional conventions, that is, are laid out in Article V. That makes it hard to deny that the founders anticipated the possibility that the states might someday call for one. This may not be “the predicted norm,” as the plan itself puts it, but it isn’t a latter-day trope that someone came up with on an internet forum.

For those of us in Texas, there’s an additional upside to Abbott’s proposal. He’s guaranteeing that the 85th Legislature spend some time debating his ideas about the Constitution, I suppose, but by the same token, he’s effectively pre-empting the revival of the ones that were on offer last year. Personally, I’d much rather see the Lege debate Greg Abbott’s arguments about the Tenth Amendment than the constitutional carry movement’s claims about the Second, or Michael Quinn Sullivan’s preferences about the First.

A similar cynicism, ironically, explains why I was so much more enthusiastic about Abbott’s plan than most of the conservatives in attendance Friday. Several were skeptical of the details of the proposal itself, such as the proposal for an amendment that would require a super-majority of seven Supreme Court justices for any rulings that would overturn a democratically enacted law. As one observed, legislatures occasionally pass laws that infringe on civil liberties.

Most, however, had more general concerns about the potential for a runaway convention. This is the main reason that conservatives are so internally conflicted about calls for a convention of the state; since there’s never been one, the implications of Article V have never been settled at the Supreme Court. Abbott’s plan argues, near the end, that the risk of a runaway convention are overstated. In Abbott’s reading, Article V allows for the states to limit the scope of a convention they might convene. The plan further argues that the legislation authorizing a state to discuss the nine amendments in the Texas plan could be contingent on discussion being limited to the nine amendments specified, and notes that it would take 38 states to ratify the results of a convention of the states. Even so, many of conservatives who heard his speech seemed to have already concluded that the idea was untenably risky; one expressed some alarm at the fact that the governor of Texas was “giving it oxygen.”

I understand that impulse. Last year, when Republican presidential candidates began debating whether the Fourteenth Amendment provides for birthright citizenship, my instinctive reaction was that no one should even think about touching the Constitution, especially at a moment when millions of Americans somehow think Donald Trump would be a reasonable president. But on Friday, I saw it the other way around. Millions of Americans somehow think Trump would be a reasonable president. We need to be realistic about what that means: as it stands, the nation is vulnerable to ideas that are not just risky, but blatantly and aggressively foolish and destructive. A convention of the states is hardly the worst idea We The People have rallied around lately.

And so, all things considered, I’m fine with the fact that the governor of Texas gave the idea more oxygen. With Friday’s announcement, Abbott brought the debate over the convention of the states into the American political mainstream. It may be true that he thereby raised the odds that recent conservative calls for a convention of the states will result, several years from now, in an actual convention. But the odds remain long. And by offering this Texas plan, with its specific provisions, Abbott also set the terms of the debate. So this much, I think is a safe bet: if America has a convention of the states to discuss proposed changes to the Constitution, we’ll all be glad to know that the person who proposed the changes has read the thing, and been fighting for it for years.

Correction: Due to an editing error, an earlier version of this post incorrectly stated that Greg Abbott had served on the Texas Supreme Court for 20 years. He was on the court from 1995 to 2001. He served as a Supreme Court justice and as attorney general for a total of nearly 20 years. We regret the error.