Josh Black is Editor-in-Chief of Activist Insight. This post is based on an Activist Insight co-publication with Kingsdale Advisors.

The Board Perspective

Pre-announcement preparations for shareholder approvals have become an increasingly onerous process, putting new strains on independent directors and management teams alike. Today, boards prepare early, knowing the robustness of the process will be closely monitored. Responses for various eventualities in which an activist emerges are tested. A smooth rollout, including the official announcement and conference calls, is underpinned by management selling the deal to key shareholders from the get-go.

“Understand that your process will be scrutinized,” says Joe Spedale, President, Kingsdale Advisors, U.S. “While your legal team will be able to tell you what is required and your bankers will tell you if the valuation makes sense, boards need to understand they will be held to a higher standard and the optics of the process are important, especially if the deal was done relatively fast or will appear unexpected to shareholders.”

In recent years, activists have run proxy contests to prevent deals, pursued appraisal rights, and made their own takeover bids—or in the case of computer pioneer Dell, all three. Carl Icahn’s rival bid and attempt to remove directors forced a mere $150 million extra from the management buyout team (all currency amounts in this post US $ unless otherwise stated), but years later a Delaware judge awarded some shareholders that had sought appraisal rights an extra 21% on top of the deal price, plus interest.

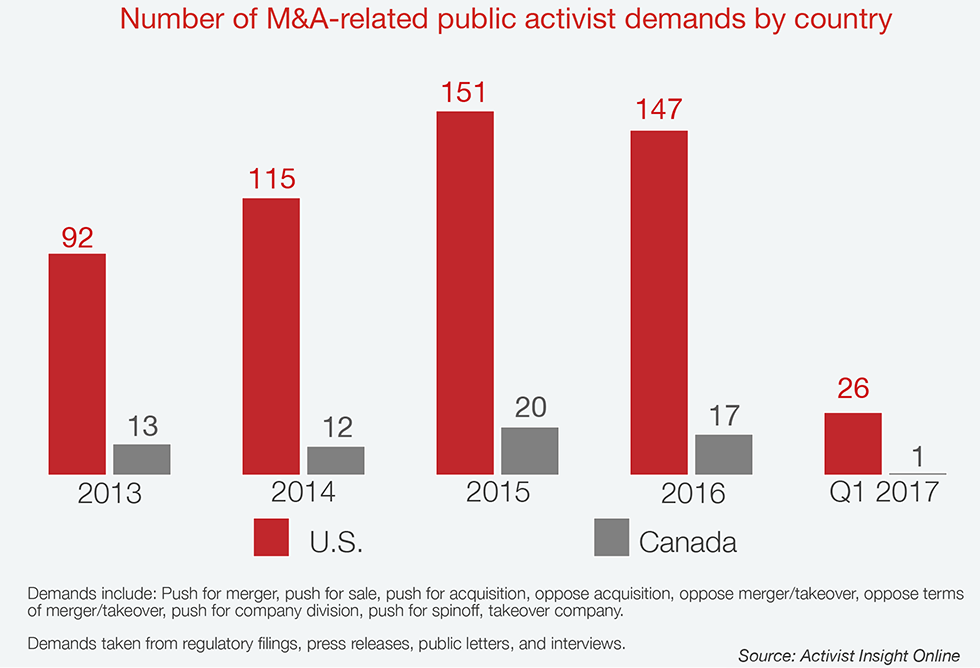

Since that 2013 campaign, M&A-related demands from shareholders have soared (see below). Some result in companies being sold that otherwise would not be in play, while in other cases deals are scrapped.

Fortunately, a number of steps can be taken to ensure deals are more resilient. Voting lock-ups are one possible step, Spedale says. If not, talk to the shareholders most likely to have reservations early and often, he says, especially if their opinions are influential. Planning a merger with Dow Chemical, DuPont did just that, inviting Trian Partners to comment on the structure of the deal privately.

Above all, proxy voting agencies play a key role in determining the ultimate level of shareholder support—or opposition. ISS typically ignores fairness opinions without detailed financial analysis, which are commissioned by the seller, adds Victor Li, Executive Vice President, Governance Advisory at Kingsdale Advisors and formerly a Senior M&A Analyst at ISS. Often, ISS will take the pulse from clients and sell-side analysts to understand whether there are already doubts, he explains. If there are, they will question management on everything from the discounted cash flow analysis to the peer group used in multiple-based valuations.

“What issuers need to be aware of is that instead of cherry-picking peer companies that are in management’s favor, it is very important to provide support and educate ISS on how the company’s peer group is generated and on what basis,” Li told Activist Insight. “If equity analysts consider other companies in the peer group, management needs a solid explanation for the difference.”

“Who’s at risk?”

Outside of basic materials, services and technology companies were the most frequently targeted by M&A demands in the U.S. and Canada, testifying to the competitive nature of those industries. Software and semiconductor companies have proven particularly vulnerable, given consolidatory pressures, while retailers and restaurant chains with significant real estate can be pressured to maximize the value of those assets.

Much M&A activism takes place at companies with a market cap of below $2 billion, as the chart below highlights. Nonetheless, the number of large deals under scrutiny has risen. Since 2014, an average of 15 issuers with a market cap of more than $10 billion have been targeted each year in North America, although most were U.S. companies.

Pursuing Strategic Alternatives

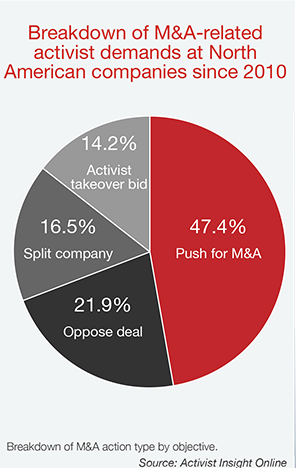

A persistent criticism of “hit-and-run” activism has activists interested primarily in forcing companies to sell themselves, allowing the investor to earn a quick buck but denying management and long-term shareholders the opportunity to enjoy the benefits of a longer standalone strategy. Certainly, activists have increasingly sought the sale of their targets in recent years. Activist Insight data shows demands for M&A doubling between 2011 and 2012 in North America rising by another third in 2014. On average, 47% of M&A-related activist demands since 2010 have been for targets to either sell themselves or merge with another company—reflecting the ease with which an investor can publish a letter or act on speculation in the market and a growing number of buyers.

Arnaud Ajdler, Managing Partner at Engine Capital, who regularly calls for companies to consider “strategic alternatives,” explained the process thus: “What we try to do is find a good quality business that is also undermanaged,” he says. “We then approach the board and say, ‘fix yourself in the public markets or sell yourself.’ Either is fine with us.”

Increases in valuations and M&A volume can boost the chances of management being open to these entreaties. “Most boards are very mindful of their fiduciary duties,” says Morgan Stanley Managing Director David Rosewater, who advises companies on dealing with activists. “If the value that can be obtained at that time through a sale is compelling enough, directors are not going to resist just to keep their jobs.”

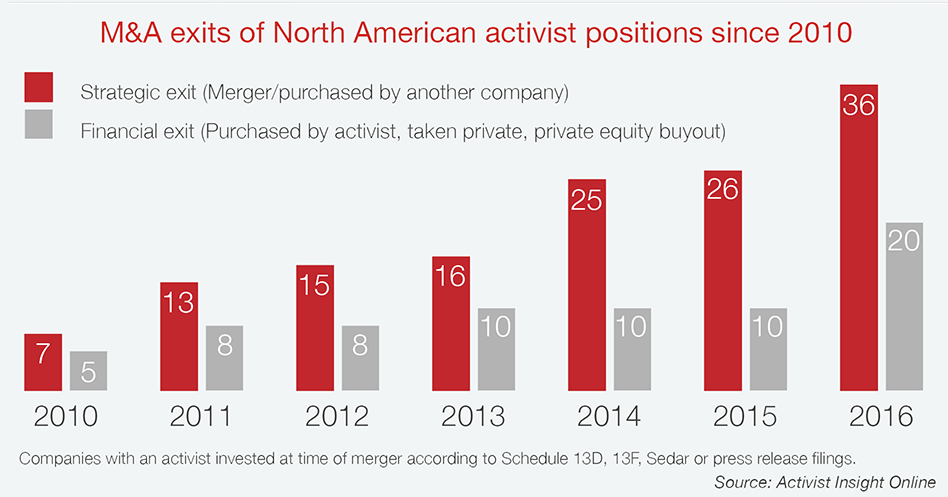

As the volume of demands has increased, so too has the inventiveness and influence of M&A activism. In 2014, for instance, activists pushed retailer PetSmart into that year’s largest leveraged buyout and partnered with a strategic acquirer to wage a hostile takeover at Allergan. Now, both strategic and private equity buyers are interested in activist targets, as the chart below highlights. Notwithstanding Ackman’s Pershing Square Capital Management being sued over the latter deal, Vinson & Elkins’ Kai Liekefett says strategic acquirers are still working with activists—albeit more covertly.

Another strategy growing in popularity is that of taking stakes on both sides of a potential strategic combination and seeking a “marriage” of the two firms. Such moves can incur antitrust issues: a deal between Staples and Office Depot was deemed bad for competition, while ValueAct Capital Partners was forced to settle a charge of not disclosing attempts to influence a change of control a few months later when it backed the merger of Baker Hughes and Halliburton.

Deal Or No Deal

Activists don’t just create M&A—they can often set out to wreck it. According to Activist Insight data, an average of 21% of U.S. and 45% of Canadian M&A activism between 2010 and the end of 2016 was aimed at preventing deals. In 2016, both markets saw record levels of activism opposing M&A.

Some of these demands may relate to stopping overly acquisitive companies from initiating more deals, but most are focused narrowly on the terms of previously announced transactions—about two-thirds in the U.S., and 84% in Canada. As Liekefett explains, “Activists typically don’t want to kill the deal, just to reprice it.”

“Bumpitrage”—so-called because activists seek a “bump” in the share price, is getting easier and more common. Of 68 opposed mergers since 2013, 18 ended up with shareholders enjoying a higher consideration, Activist Insight found, with the average increase just under 21%.

But those cases were a minority. Several deals with equity components worsened, and most deals continued on the same terms. The problem with fighting an announced transaction, Ajdler says, is that “you work very hard and at the end, either the buyer walks away and the stock goes down significantly, or there is a small increase in price and most investors, especially arbitrageurs, cave.”

“Failed votes rarely come back on improved terms,” Spedale warns.

At other times, an activist might argue that a company has neglected potential avenues for value creation. “Now, if a company hasn’t been shopped, then it’s a different story, because you can flush out other bidders,” Ajdler explains. “But most companies tend to shop themselves these days.”

Such was the case in Carl Icahn’s unsuccessful attempt to push Family Dollar to merge with Dollar General in 2015. Family Dollar had already held secret talks with Dollar Tree and discounted Dollar General on antitrust grounds. After warning that Icahn had nearly disrupted an achievable deal, the Dollar Tree transaction sailed through. Having beaten the announcement, Icahn still elicited a profit from the trade, unlike those that followed him.

Still, certain circumstances can encourage an outbreak of shareholder opposition. Longstanding shareholders, including pension funds and value investors, can be stirred if they believe a stock they own is being sold at a low price or less-than-advantageous time. If the deal is likely to offer synergies, the pressure can be more intense. AMC Entertainment ended up paying more than 10% extra and offering a cash-stock mix option to acquire Carmike Cinemas in 2016, following vocal opposition from two investors. Bumpitrage is also an easier game to play with tender offers, which can be amended and extended and don’t require a shareholder meeting.

The Breakup Shakeup

Approximately 17% of M&A activism in North America seeks the breakup of companies through the sale or distribution of business divisions, running as hot as a quarter of demands in some years. Public letters, proxy contests and non-binding shareholder proposals are all common tactics for activists with this in mind, as with Carl lcahn at eBay or Relational Investors and the California State Teachers Retirement System (CalSTRS) at Timken.

Often proactive by nature when the company is intent on remaining a conglomerate, these campaigns have on occasion been more reactive, as with Darden Restaurants’ sale of its Red Lobster restaurant chain. Starboard Value believed management was making a mistake, hoping instead to spin all of Darden’s property into a real estate investment trust (REIT). Unwilling to criticize Red Lobster’s business and therefore unable to explain why it was selling it to private equity firm Golden Gate Capital, Darden was routed in a proxy contest later that year.

Some demands turn on a dime. In 2014, Sandell Asset Management ran a proxy contest at Bob Evans Food, narrowly missing out on a majority of the board, which would have allowed it to separate a frozen foods business run by the restaurant chain. More than a year later, the company changed its CEO and began engaging anew with the activist. In January 2017, it sold its restaurant business to a private equity firm, creating the pure-play frozen food division the activist sought.

Deal structure matters

How a deal is structured can play a critical role in its eventual success. Mergers requiring a shareholder vote can be risky, especially if the consideration is wholly or partly stock-based and can be buffeted by choppy markets, as with the AB lnBev-SABMiller deal after Britain voted to leave the European Union. Dead votes, when shareholders of record sell before voting or before a revised bid is made, can also be an issue.

Tender offers, which can be easily amended and extended, are often more susceptible to arbitrageurs playing holdout, as with Carl lcahn’s recent acquisition of Federal-Mogul. ISS and Glass Lewis are less likely to opine on tenders—another bonus. In certain conditions, Delaware companies have been able to move to a merger after the majority of shares have been tendered, an attractive option as a shareholder vote with a simple majority requirement then becomes a formality.

Finally, deal protections such as no-shop clauses and termination fees can rile investors, transferring the risk from the buyer to the shareholder meeting.

Hostile M&A

Special meeting requests, proxy contests, and poison pills increasingly help to blur the lines between activism and hostile M&A. In 2016, French pharmaceutical company Sanofi launched a consent solicitation to remove directors of its target Medivation, requiring only majority support under the latter’s by-laws, although it was later trumped by a bid from Pfizer.

The year before, Allergan had seen its case against a takeover by Valeant weaken as it sought to deny activist Pershing Square a requested special meeting where directors would have been up for removal. Again, it needed a white knight in the form of Actavis to defeat the Valeant bid. Such moves can come at a price—tronc defeated a hostile bid from Gannett with a private placing of shares to a friendly investor, but relations between chairman Michael Ferro and Patrick Soon Shiong deteriorated in 2017, creating more difficulties for the publishing company.

What Lies Ahead?

Whatever the precise form, M&A activism looks likely to persist. It can be relatively cheap, using public letters to draw attention to opportunities, and lucrative; of 68 opposition campaigns, only a minority succeeded but the overall average increase in consideration was 5%. Yet it can also be toothless if most shareholders back management.

The experience of 2016 suggests volatile markets and a lull in deal volume can make investors restive—that year, demands opposing M&A doubled in the U.S., while attempts to promote M&A activism fell by one-quarter. In booming markets, activists are more willing to attack boards and management teams and run proxy contests on almost the sole issue of whether a company should be sold.

Some see private equity trending the other way—becoming more activist. Several private equity firms have taken large positions in publicly listed stocks in order to drive change. At NRG Energy, in what may be the first case of its kind, Bluescape Resources formed a group with Elliott to push for board changes. While New York City Comptroller Scott Stringer called the settlement “hasty and deeply flawed,” Bluescape’s director was re-elected. With competition for buyout firms increasing, some reason that bids by private equity firms could become more hostile, or indeed activist.

In the immediate future, it seems unlikely that activists will be any less important to the functioning of M&A than they currently are. Instead, many expect to see the partnership invented by Pershing Square and Valeant Pharmaceuticals replicated in a slightly different form, despite its current legal troubles and the dismal subsequent performance of Valeant. So far, the tactic has only been replicated by Lone Star Value Management, at much smaller companies.

Other recent episodes show activists flirting with the idea of pursuing strategies closer to private equity. Elliott Management, which helped broker the largest ever leveraged buyout in the technology space—Dell’s acquisition of EMC—partnered with Francisco Partners to acquire Dell Software Group as part of the transaction. It now has a fully functional team, California-based Evergreen Coast Capital, providing private equity to the tech industry.

Pressure for traditional investors to take an active role overseeing portfolio companies will undoubtedly require more engagement from boards looking to pilot through M&A. Tougher standards from proxy voting advisors and deeper analysis by shareholders could make the post-announcement process more important and time-consuming. In this environment, there will be plenty of fuel for dedicated activists.

“Whether running a vote no campaign or pushing a company toward a particular transaction, the sheer number of activists, their assets under management, and the fact they are targeting small and mid-size companies in recent years makes it clear we will see much more in the coming years,” concludes Spedale. “M&A is cyclical but activism is not.”

The complete publication is available here.

Print

Print