Paula Loop is Leader of the Governance Insights Center at PricewaterhouseCoopers LLP. This post is based on a PwC publication by Ms. Loop.

How well management handles key risks often determines whether the company will achieve its strategic goals.

It’s easy for boards to get bogged down discussing financial and compliance risks. But that can mean that they’re not paying enough attention to risks that are truly critical. Directors need to make sure they’re focusing on the right key risks—the ones that could spell success or failure for the company.

Understanding how well management is handling risk priorities

Companies manage many risks, but those with an effective enterprise risk management (ERM) program are able to identify and prioritize which of those risks are most important. So the first step to overseeing a company’s key risks is for directors to figure out if the company’s ERM process is working to produce the “right” list of top risks. For tips on how to do that, see How your board can ensure enterprise risk management connects with strategy.

In our experience, boards often spend too much of their limited time discussing financial or compliance risks. While those are important, strategic and operational risks can upend a company just as quickly. Studies show strategic risks are the ones that are far more likely to destroy value [1] and significantly impact whether a company meets its strategic and operating objectives.

While companies share some common risks based on their sector—like having to react to significant regulatory changes—each company faces unique key risks based on its strategy and business model. Those can range from flawed merger integration to a lack of product innovation in the face of changing customer demand.

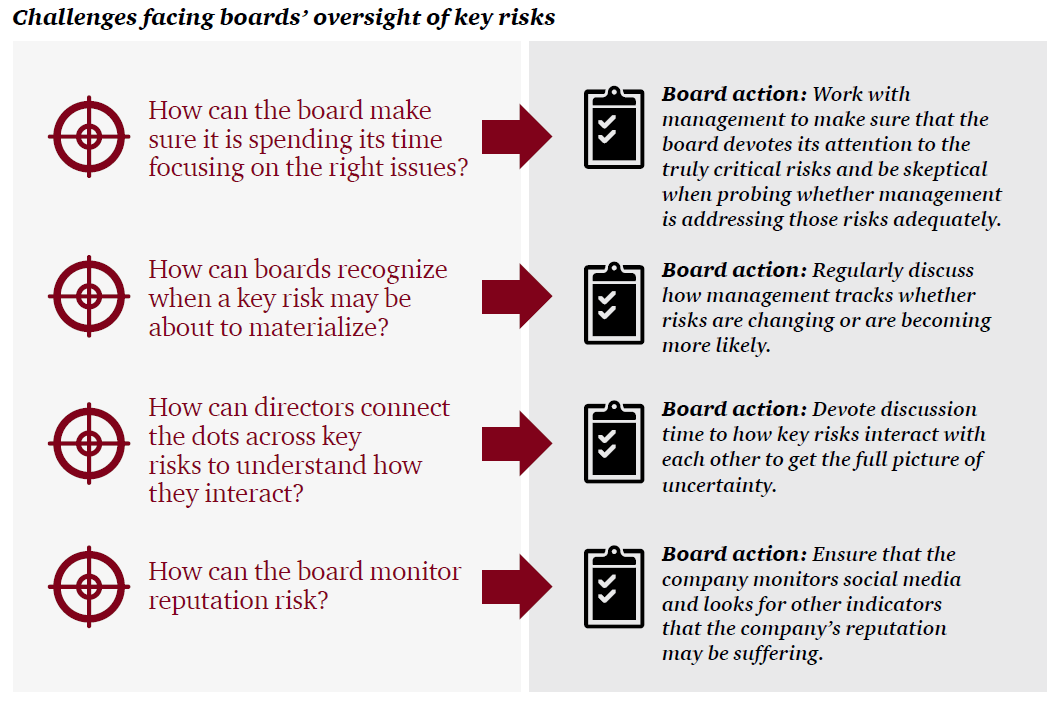

Challenge: How can the board make sure it is spending its time focusing on the right issues?

First, simply getting a “list of risks” is more problematic than it would seem. Management often identifies key risks based on a fairly simple assessment of impact and likelihood. Based on our experience, such lists:

- Rarely tie to the strategic objectives that the risks might impact

- May not reflect the fact that strategic objectives are not always created equal

- Seldom provide insight into how the key risks should be prioritized and so offer little guidance on how to deploy resources

- Often fail to identify which objectives will not be achieved if the risk does materialize

And so it’s difficult for directors to know whether the key risks they’re being told about are truly strategic.

Additionally, directors without extensive experience in the company’s industry can struggle to fully appreciate the nuanced issues underlying key risks. Without that understanding, it’s tough to judge whether management is doing enough to handle the risks. And directors who’ve seen things go very wrong at other companies may wonder whether they can trust management’s assurances that “everything’s under control.”

Board action: Work with management to make sure that the board devotes its attention to the truly critical risks and be skeptical when probing whether management is addressing those risks adequately.

First off, take a fresh look at the list of risks that management presents. If they don’t appear to be strategically important, send management back to the drawing board. Insist that senior executives and business leaders be involved in redeveloping the list to bring a strategic perspective.

If it looks like the management team is struggling to get to the right list of key risks, the board might suggest they focus on answering such questions as:

- Which risks impact multiple strategic objectives (and are therefore likely to be of greater concern)?

- Which strategic objectives have the greatest number of risks tied to them?

- Are there any strategic objectives for which either the number and/or severity of associated risks changed?

- Which risks impact the company as a whole, or could easily escalate from a transactional/ operational level risk to being strategic?

Once the board is satisfied that management’s list of key risks consists mainly of those relating to strategy, consider having the full board take the lead in overseeing them. As a result, board committees would oversee fewer key risks on behalf of the board—and focus instead, for example, on key compliance risks that tie closely to the committee’s purpose.

As mentioned earlier, not all strategic objectives are created equal. A board could decide it wants to discuss the most important objectives (along with their corresponding risks) at every board meeting.

Boards also have many other options. One is to cover certain of the key risks as part of the board’s strategy discussions. Indeed, a board strategy discussion would feel incomplete if it didn’t address risks like disruptive technology that competitors are developing or the challenges around the introduction of a major new product line or sustainability issues that will impact the company’s future operations. For key risks that perhaps don’t relate as closely to strategy discussions, figure out how often the board should discuss them, then allocate them to future board agendas.

It may still make sense to assign certain risks to different committees—the compensation committee may focus on revamped compensation plans while the technology committee focuses on new IT systems integration. But make sure the committee chairs share important insights and conclusions with the full board.

Determining how often you should review key risks

- Key risks that are “steady state”—probably once a year

- Keys risks that are more dynamic in nature—perhaps two or three times a year, or even more often

Answering the questions of where and when to discuss key risks is relatively easy. Figuring out how to cover the risks effectively is more challenging.

Periodic deep dives

A deep dive is one good approach to understand each key risk more fully The risk “owners”—business unit or functional executives—should share materials before the meeting so directors can understand the nature of the risk, its potential impact on strategic goals, how it’s being managed—including acceptable limits—and what kind of controls are in place. Directors can then spend meeting time discussing the risk and how management’s assessment maybe shifting-whether the potential impact is more severe or changing more quickly than expected for example. If so, directors can then slot time into an upcoming meeting agenda as needed and even consider engaging an outside expert for another view on an especially thorny key risk.

Directors can seek other opinions on how management is handling a specific risk by asking ERM, compliance and internal audit for their views.

Want comfort on whether management is doing enough to address key risks?

Ask whether the resources used in managing particular risks make sense given the objectives they could impact.

Frequent discussions of ongoing risk

If the risk is continually evolving or threatening—cybersecurity, for example—directors may want to hear about it more often. Those conversations should involve the responsible executive and others who play key roles. For cyber, that discussion could include the chief information officer or chief information security officer. And if a risk event is imminent, management needs to be ready to talk about the timing and severity of the risk materializing, its impact on strategy as well as how they plan to handle any potential crisis.

Considering external risks

Management has limited control over key external risks. But executives ought to be telling the board how they’re tracking and analyzing the impact of risks that aren’t under the company’s control—like geopolitical unrest. While there is little an individual company can do to lessen external threats, management needs a plan to manage their possible effects.

Challenge: How can boards recognize when a key risk may be about to materialize?

Major risk events tend to have many, often cascading effects. For example, a natural disaster may damage company plants, disrupt a company’s supply chain and endanger company employees. These kinds of distinct events are easier to spot than, say, eroding political and financial confidence in a new market or declining employee engagement.

Board action: Regularly discuss how management tracks whether risks are changing or are becoming more likely.

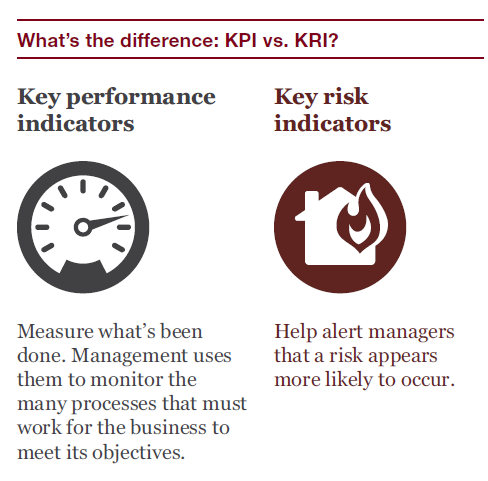

Early warning signs, often known as key risk indicators (KRIs), can be especially helpful for directors. These metrics can give boards a feel for how management is scanning the risk horizon for red flags. KRIs should be closely linked to key performance indicators (KPIs) because in the end, effective risk management ought to help drive expected performance.

Boards will want to discuss with management the handful of KRIs that link to strategic objectives. Each committee (and the full board) may have KRIs to review. KRIs don’t predict the future—they allow management to monitor possible changes in either the impact or the likelihood of key risks to help minimize surprises so it can take action. For example, unemployment may signal to a retailer that holiday sales won’t be as robust as expected and it may be time to lighten inventory or reduce staffing. KRIs also allow the board to be kept informed. And if a key risk indicator signals that the risk is more likely, that should be part of board discussions with management.

How does management develop KRIs? If there’s an ERM function, it’s their job to work with management to develop key risk indicators that align with key performance indicators. But even without a formal ERM group, management should be familiar enough with warning signs of changing risks or new risks to monitor how those changes might impact performance.

What if your company doesn’t have KRIs? Discuss with management their outlook on near- and longer- term strategy to learn what signals they use to anticipate changes in the key risks and how they might respond And if you think more formal KR!s can contribute to your risk oversight role, ask management to develop some for the key risks. But it helps first to have a clear risk appetite tied to strategy to provide parameters for risk taking. (See our module, How your board can influence culture and risk appetite.)

Finally, understand that a company that has identified and is tracking KRIs is only monitoring risks by doing so. You can’t assume the presence of KRIs means risks are being managed properly.

The bottom line is that even if a company lacks sophisticated ERM, regular discussions with management about what’s happened, what’s new and what’s next can help your board oversee key risks.

Challenge: How can directors connect the dots across key risks to understand how they interact?

Some companies think they’re done once they’ve plotted individual risks on a heat map to show impact and likelihood. But it’s rare that one risk doesn’t trigger several impacts, some of which relate to other risks. For example, the wrong compensation plan may drive people to take excess risk or compromise plant safety to meet unrealistic production and financial targets. Faulty incentives might even prompt regulators to focus attention on a company to see how they might “fix” the problem. But a siloed focus on individual risks prevents management from identifying how risks intersect.

Understanding how risks intersect is challenging for any company, and boards too often aren’t able to have meaningful discussions on the topic either.

Why is that? If the board or a committee discusses different key risks in different meetings, it may not be possible to see how risks can impact one another. And, if risks are discussed in committees but not included in full board discussions, it’s easy to miss the magnified impact of several risks happening together.

Board action: Devote discussion time to how key risks interact with each other to get the full picture of uncertainty.

Ask the business risk owners—and the chief risk officer, if there is one—if they understand how risks impact each other and what the consequences of the inter-relationships could be.

Directors will want to make sure that when they talk about key risks with management and with each other, the discussions also include possible ways these risks impact the company’s ability to meet strategic and operating objectives.

For those risks that are allocated to a committee to oversee, committee reports to the full board become more important. They should include insights about risk interactions from management—this is also where cross-committee membership can be helpful.

Challenge: How can the board monitor reputation risk?

Chances are that your company’s reputation was one of the deciding factors in your joining the board. A company’s reputation is key to its value for shareholders and all stakeholders, so it’s certainly a board-level issue. But, it’s not clear how directors should oversee reputation.

What makes overseeing reputation risk tricky is that it’s usually another risk that triggers reputation risk—faulty products and loss of customer confidence, repeatedly missing earnings numbers and loss of investor confidence, or an industrial accident and loss of employee confidence, for example. And reputation problems can quickly impact the bottom line especially at consumer products companies. Think of consumer response to poor working conditions in overseas factories, health scares in restaurant chains or the loss of customer personal information at retailers.

Reputation matters to all stakeholders. A good reputation can attract investors, attract top talent, keep employees engaged and bring in customers. But a poor reputation can have the opposite effect—as well as draw the attention of politicians and regulators who may feel obliged to investigate.

Reputation problems often continue to expand and impact a company long after a risk event becomes known—and long after the company has fixed the original issue. For example, undue pressure to meet unrealistic performance targets can lead to a company being viewed as a bad place to work, with long-term hiring implications. That might mean the company would have to pay more than the market rate for talent. It might also mean a missed opportunity for employees to be good brand ambassadors for the company.

Board action: Make sure the board understands and considers the impact key risks have on the company’s reputation.

First and foremost, the CEO is the steward of a company’s reputation. Managing reputation can be complex, so ensure this subject is addressed as part of any board discussion of key risks.

Reputation vs. brand

Reputation is how a company or product is perceived in the marketplace. Brand—which is the image the company creates—impacts reputation. A solid brand typically leads to a good reputation. The big difference? While a company can control brand messaging, it can only attempt to burnish or repair a reputation.

How can a company gauge reputation risk? Executives can use scenario planning when developing strategy and considering risks to that strategy. Such techniques play out the implications for reputation backlash from key risk events occurring. For instance, if customers are expecting a new product release during the fourth quarter in time for the holiday season and it doesn’t happen, then that missed opportunity can erode trust in the company and drive customers to competitors’ products. Even doing a stellar job to manage customer expectations may not protect a company’s reputation in such situations.

Before a company’s reputation suffers possible damage, directors will also want to know that there is a viable crisis management plan that assigns roles and activities to different players. A well-developed crisis management team will have extensive plans to respond to different scenarios. Employees from many segments of the company—operations, security, communications, legal and others relevant to the crisis itself—will play key roles in executing the plan. The crisis management team ought to carry out periodic table-top exercises to practice its response to the crisis and the related reputation fall-out. It’s not possible to know which crisis will happen, but having a well-defined set of procedures and roles can keep your CEO from being caught flat-footed in the aftermath. (See our module, How your board can be ready for crisis.)

Directors will also want to understand how the company manages the reputation risks from social media. Social media platforms provide powerful tools to connect with a broad audience—including customers and potential employees. People readily turn to Facebook or Twitter to express their views about a company and its products or services. And so companies should monitor what is being said about them on such sites—and respond to complaint trends as part of guarding the company’s reputation. This is vital given the millennia! generation is especially likely to believe what it sees on social media more than a company’s own messaging. That means your company’s reputation is literally in the (smartphone holding) hands of your customers (or employees).

In the end, one of the most important things directors can do when it comes to overseeing reputation risk is to learn to ask the right questions—and ask them in different ways. This is one area where having diverse opinions around the board table can really help. Even though most directors and executives may think an issue is no big deal, having a director insist that the repercussions be investigated can bring a needed perspective to the conversation.

In conclusion…

Once directors feel comfortable the company has a good ERM program, they’re able to focus more of their attention on key risks. Asking the question “and then what might happen?” multiple times can help the board play our the impacts of these key risks—and it lets you know that management has put some hard thinking in to how key risks influence performance.

Endnotes

181% of 103 companies studied lost significant value because of “strategic blunders”. Source: Booz and Company, The Lesson of Lost Value, November 2012.(go back)

Print

Print