Rupal Patel and David Ellis are partners at EY. This post is based on an EY publication by Ms. Patel and Mr. Ellis. Related research from the Program on Corporate Governance about CEO pay includes Paying for Long-Term Performance (discussed on the Forum here) and the book Pay without Performance: The Unfulfilled Promise of Executive Compensation, both by Lucian Bebchuk and Jesse Fried.

In recent months executive pay has received an unprecedented level of attention from a wide range of stakeholders. While Remuneration Committees, executives and investors in many businesses may feel that current pay structures are working well and fit for purpose, the intensity of noise we are experiencing tells us that it is no longer reasonable for any organisation to assume that there is nothing it needs to be concerned about.

First indications from the 2017 AGM season show that in many cases the noise in the system is now turning into real opposition. Many would seek to explain away this opposition as being specific to a business, or focussed on a discrete issue. We at EY believe that this is now wishful thinking.

Much of the noise in the system derives from the view held by some that executive pay is simply too high. A suggested solution is to regulate pay by imposing a cap on the amount an individual may receive. Whilst capping executive pay would be relatively straightforward to execute, we believe that it will not fix the root problem and could create considerable complexity in itself.

That is not to say that change in the executive pay arena would not be welcome. There is work to be done in several areas including governance, communication and alignment of interest. However, one aspect on which stakeholders appear to be agreed is the need for the simplification of executive pay.

EY’s view is that this simplification agenda cannot be addressed by tweaking aspects of the traditional package. This is not about the number of performance measures used or the length of deferral applied. It is about acknowledging that a desire for simplification requires agreement on what is core to an executive pay strategy and to focus on that exclusively.

EY feels that many aspects of the today’s pay structures, which have been viewed as integral to the traditional model, may not be the most efficient way to deliver remuneration or may simply be no longer relevant.

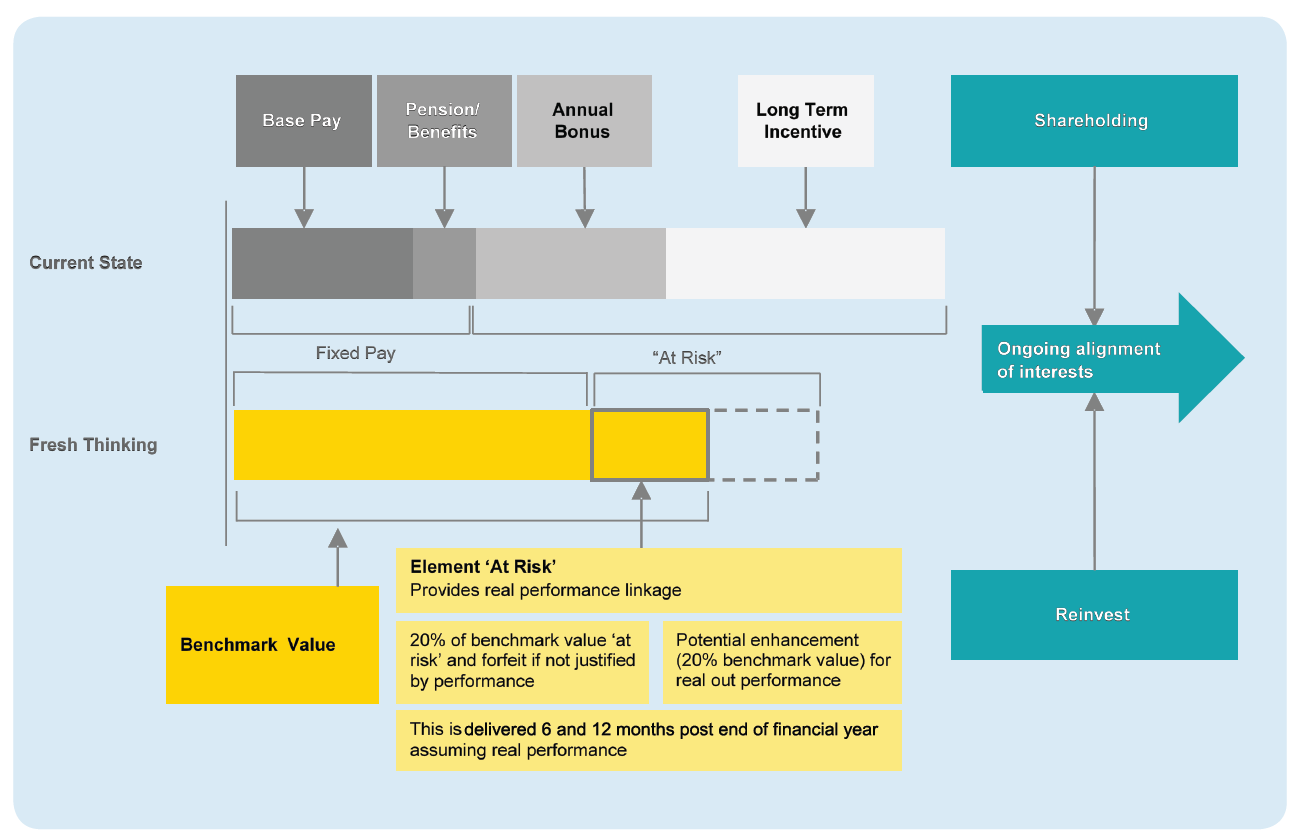

Whilst there are any number of alternative structures and possible approaches to improve the status quo, EY believe the current challenges cannot be addressed by existing remuneration models. Accordingly we have designed a new model, the One Element Pay Model.

Under such a model, companies:

- Pay executives for the work they do.

- Pay them a bit more if they generate better than expected outcomes.

- Pay them a bit less if they undershoot expectations.

- Require that they buy shares every year with a meaningful portion of their remuneration.

EY believe the One Element Pay Model for executives can offer advantages not only to businesses of many shapes and sizes, but also the diverse group of stakeholders in the executive pay debate.

Print

Print

3 Comments

With all due respect to the authors, and despite my enormous respect for EY, I do not see how a “one-size-fits-all” model will be helpful to the discussions in the boardrooms regarding executive remuneration. The authors start by saying that “stakeholders” have agreed on “the need for the simplification of executive pay”. Which stakeholders? Those who want to make their analytical jobs easier by having a single point of comparison? Those who have a political agenda and want to criticize disparities in pay with easy benchmarking? Those politicians who thought that it would be easy just to write a pay ratio into Dodd-Frank and the criticisms would cause CEO heads to roll?

What about the stockholders, who may not mind overpaying executives a few million if they get a better return and the opportunity for a better return in the future? what about the board members who may want more complexity to help them manage managers who have gotten in a rut? This article may be an interesting academic exercise, but it does not take into account practical realities — which I would expect EY to do.

In some cases, more complexity is required. What happens when goals are set at the start of the year, but market conditions immediately change so that the goals are easily obtained or impossible to obtain? The “simplistic response” is unclear. A more complex response would require the board to incentivize based on current conditions — 162(m) permits shorter term goals and it may be appropriate to reset, even if more complex.

At the other end of the temporal scale, what about long-term goals that don’t fit neatly into SEC reporting periods?

This scholarship may be better informed with some real world examples.

Dear Robert

Thank you for your comments. I am not sure we are a million miles apart on some of the issues you raise. It may be useful if I clarify three points in particular.

First, the approach described in the extract above is not (and is not intended to be) a one size fits all model. It contains a number of features and is designed around a number of themes that are all relevant – but certainly are not expected to be adopted in totality by any business without consideration of particular facts and circumstances.

Secondly, the call for simplification was a consistent message – heard when we spoke to investors, management teams and remuneration committee chairs. Indeed it was the one consistent message we heard from all three of these stakeholder groups.

Finally, the challenges you describe above contribute in no small part to the desire to move closer to a model that seeks to remove the emphasis on target setting, discretion and volatility. And place more emphasis on the value of the skills an individual can bring to bear and ensuring that the value of those skills is paid for. Using pay as a proxy for performance management, or as a stick to beat management with when commodity prices fall or exchange rates fluctuate has, in our view, limited value for shareholders.

The crux of the thinking is whether we are able to construct pay mechanisms that are valued by recipients, drive sensible long term behaviours and are less volatile in quantum terms. The conclusion we reached, is that these three aims are within reach. Which is additive to the debate around executive pay, but clearly not determinative of outcome.

I believe the quality of the debate around executive pay improves when better questions are asked. This piece of thinking, in my view, poses a question and no more. We may have to agree to differ on this, but I can assure you that the foundation this approach is built upon is framed entirely by real world examples.

Kind regards.

David Ellis

The points raised in the article are already known components of a good remuneration system. What we need to remember is that when people complain about overpayment of executives they are indirectly questionining the value the executives are creating. I think the debate should be about how to seperate true executive contribution(performance) and reward it from peformance that comes due to chance factors where the executive did not play a part.If this problem can be resolved it is easy to then design the reward mechanism. The second problem is that linking CEO pay to average pay in the organisation through a ratio is a way of indirectly saying CEOs must not earn too much relative to average pay. This can be solved by sharing the value cretaed if any equitably throughout the organisation instead of just giving this to the top guys. Pay governance issues can not be addressed through regulations. You need ethical leadership in the first place.